At Duesseldorf’s historic Malkasten artists’ association on Nov. 19, the Nazi-looted painting, Storm at Sea, by the Dutch master Johannes Hermanus Koekkoek, was returned to the heirs of art dealer Max Stern.

Representatives of the Max and Iris Stern Foundation and its three university beneficiaries, Concordia and McGill of Montreal and Hebrew University of Jerusalem, were in the German city to receive the artwork.

The painting was slated to be sold by a consignor, whose identity is not being made public, at the Hargesheimer art auction house in Duesseldorf.

READ: GERMAN TOWN RETURNS ART TO MAX STERN ESTATE, THEN BUYS IT BACK

It is the 18th painting that has been recovered since the Max Stern Art Restitution Project (MSARP), which is based at Concordia, was launched in 2002.

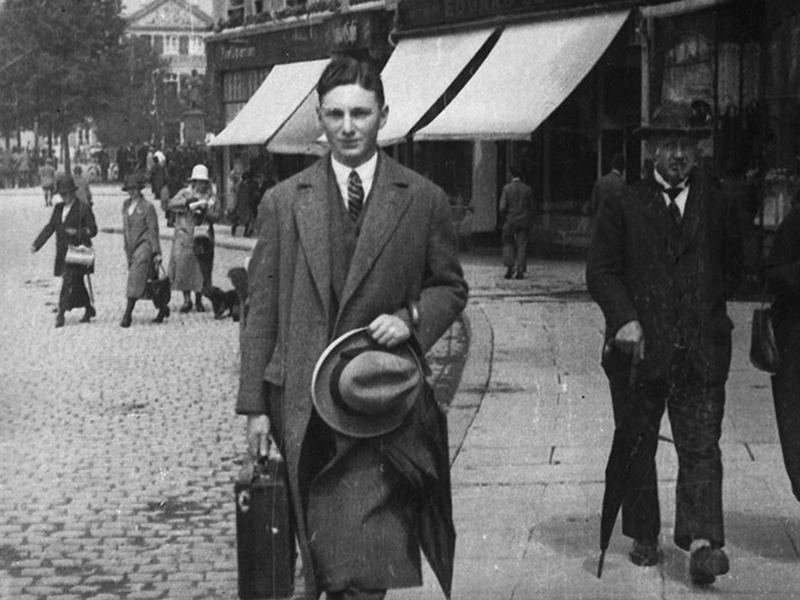

The return of this painting was particularly poignant, as Stern, who died in Montreal in 1987, was a native of Duesseldorf. He was forced by the Nazis to liquidate the inventory of the art gallery he owned there, before he fled to Britain in late 1937.

The painting was tracked down following a tip from within the European art trade.

The MSARP, working with the new Munich-based Stern Co-operation Project and New York State’s Holocaust Claims Processing office, advised the auction house’s owner, Frank Hargesheimer, and the consignor of the painting’s tainted history.

“It was retuned to the Stern Foundation without challenge,” said Clarence Epstein, MSARP’s co-ordinator.

Stéphane Dion, Canada’s ambassador to Germany and special envoy to the European Union, was present for the ceremony.

“Art restitution is an integral part of Holocaust remembrance, respect for human rights and international justice,” he said.

“I would like to congratulate the Stern Foundation and the Duesseldorf auction house on their agreement and exemplary commitment to redressing past injustices.”

The Stern Co-operation Project was established this year with major funding from the German government. Its team of researchers from Germany, Canada and Israel are looking into the fate of the Stern family and the larger ongoing issue of justice for the victims of Nazi spoliation. Many of those valuables are believed to still be in Germany.

But not everyone in the German art world is as co-operative as the individuals involved in this case, Epstein said.

“The amicable agreement with the Duesseldorf auction house is in steep contrast to the handling of several of our claims on paintings in City of Duesseldorf museums,” he said.

“We are equally concerned with the practices of the Lempertz auction house in Cologne, where Stern’s gallery inventory, including the Koekkoek, was sold by force in 1937.”

The amicable agreement with the Duesseldorf auction house is in steep contrast to the handling of several of our claims on paintings in City of Duesseldorf museums.

– Clarence Epstein

Epstein said that Lempertz, which is still in business, has repeatedly denied any historical wrongdoing, and have ignored the Stern Foundation’s claims.

“As a case in point, during this fall’s Lempertz sales, the MSARP team flagged the work Cairo by Emile Charles Wauters, which was also sold by force like the Koekkoek in the 1937 sale,” said Epstein.

“Auction house officials did not respond to formal queries about its problematic past and instead tried to sell it. Even more disconcerting was how German law enforcement was unwilling to investigate the matter, despite the work being listed as stolen on the Interpol database.”

Epstein hopes an upcoming conference in Germany may lead to a more consistent recognition of the obligation to restore looted art to the rightful owners.

The federally funded conference, which is taking place in Berlin from Nov. 26-28, marks the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.