The return of a historically significant 17th-century painting to the Max and Iris Stern Foundation by the small Bavarian town of Weinsberg is being held up as an example of the co-operation that is possible between Germany and claimants of Nazi-plundered art.

The ceremony to officially hand over Women of Weinsberg on May 7 took place in Munich, rather than Duesseldorf, as was originally planned. This is because the Max and Iris Stern Foundation is at odds with Duesseldorf’s mayor, due to his abrupt cancellation of the long-planned exhibition, Max Stern: From Duesseldorf to Montreal, at a municipally run museum in November.

Mayor Thomas Geisel, who had originally cited ongoing claims on Max Stern’s art as a reason for cancelling the exhibit, reversed the decision a month later, in the face of an international outcry and criticism from Germany’s federal government.

The exhibition was to have opened in Duesseldorf’s Stadtmuseum in February, then travel to Israel in September and finally come to Montreal’s McCord Museum next year.

The exhibition, which was receiving both financial and expert support from Canadian partners, was initially postponed to this fall, to coincide with an international symposium on Stern and the restitution issue. But in late April, the City of Duesseldorf announced that it will be delayed until September 2019.

How the revised exhibition will differ from the original concept is unknown. The two Canadian curators – Philip Dombowsky, who is responsible for the Stern archives at the National Gallery of Canada, and Catherine MacKenzie, the Concordia University art historian attached to the Max Stern Art Restitution Project – recently withdrew from the project altogether. The lead curator, Stadtmuseum director Susanne Anna, was also dismissed by the city.

READ: DUESSELDORF REVERSES ITS DECISION TO SCRAP GERMAN ARTIST MAX STERN’S EXHIBITION

The Stern foundation is seeking reimbursement of the 20,000 euros ($30,000) it contributed, having lost confidence in the city’s intentions.

Launched in 2002, the restitution project is administered by Concordia, a principal heir of the Stern estate, along with McGill University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Women of Weinsberg by Dutch painter Gerrit Claesz Bleker (1592-1656) is the 17th painting that has been recovered by the project.

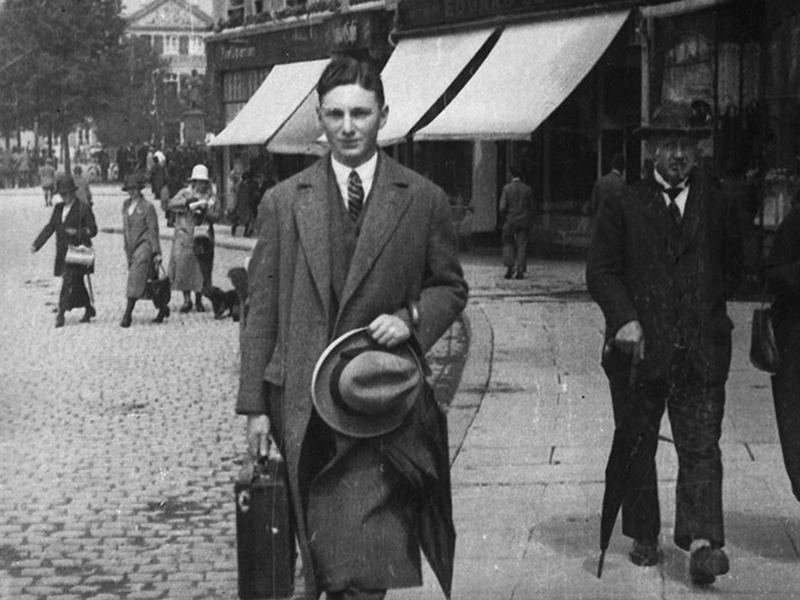

Stern (1904-1987) was forced by the Nazis to liquidate the hundreds of works in his Duesseldorf gallery in 1935. His final 200 paintings were forcibly sold at auction in 1937, after which he fled to England.

He would become one of the most prominent art dealers in Canada, as the proprietor of the landmark Dominion Gallery on Sherbrooke Street in Montreal.

Stéphane Dion, Canada’s ambassador to the European Union, as well as World Jewish Congress officials and municipal leaders attended the ceremony on May 7.

In 2014, Stern project researchers confirmed Stern’s ownership of the Bleker painting by examining correspondences between Stern and the director of the Netherlands Institute of Art History in the 1930s. Soon after, the Holocaust Claims Processing Office of the New York State Department of Financial Services, acting on behalf of the Stern foundation, submitted a claim to the town of Weinsberg, which is located about 365 km south of Duesseldorf.

The painting depicts the town’s foundational story, when its castle was besieged in the 12th century by King Conrad III of the Holy Roman Empire. Conrad III offered the women the opportunity to flee with whatever they could carry, so they put their husbands on their backs and their children under their arms, leaving their material belongings behind. Impressed by their faithfulness and ingenuity, Conrad III spared them all.

Unaware of its tainted past, the town of Weinsberg, which today has a population about 12,000, bought the painting from a private collector 50 years ago.

Given the importance of the work to Weinsberg, the Stern foundation has agreed to, in effect, sell it back to the town, which has displayed it in the Weibertreu Museum for the past 30 years.

The arrangement, which was brokered by the Office for Provenance Research of the German Lost Art Foundation, was made possible by donations from the Cultural Foundation of German Federal States and the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation.

“The restitution of this painting is testament to the fact that, through the dedicated efforts of individuals and organizations, a small measure of justice can be brought to this dark period of history,” stated Dion. “I congratulate everyone involved and strongly hope that the Max Stern Art Restitution Project will continue to receive all possible support in Germany.”

The restitution of this painting is testament to the fact that, through the dedicated efforts of individuals and organizations, a small measure of justice can be brought to this dark period of history.

– Stéphane Dion

When the agreement was finalized in the fall, a ceremony was planned to be held at the Duesseldorf Stadtmuseum to coincide with the exhibition. But “with the surprising cancellation of the show by the City of Duesseldorf, due to the stated concerns about restitution claims, the ceremony was moved to Munich,” said Clarence Epstein, head of the Stern restitution project.

The Stern exhibition had its genesis in 2014 when the City of Duesseldorf restituted a self-portrait by 19th-century German artist Wilhelm von Schadow to the Stern foundation, which allowed it to continue to hang on permanent loan in the Stadtmuseum.

However, a current claim on another of Schadow’s works, The Artist’s Children, in the Duesseldorf city collection is being contested.

In addition, since July, another Duesseldorf institution, the Kunstpalast Museum, has been at the centre of a disputed claim by the Stern foundation over the 19th-century Sicilian Landscape by Andreas Achenbach. The private collector who possesses it says he bought it in good faith at an auction in London in 1999.

“We are hopeful that the Weinsberg return and exemplary efforts of various state and national partners will compel other German municipalities, museums and collectors to openly address restitution matters,” said Epstein. He lauded Weinsberg for acting morally, contrasting its co-operation to Duesseldorf’s intransigence.

Under German law, the statute of limitations on reclaiming stolen property is 30 years, with no specific exemptions made for Nazi-era spoliation.