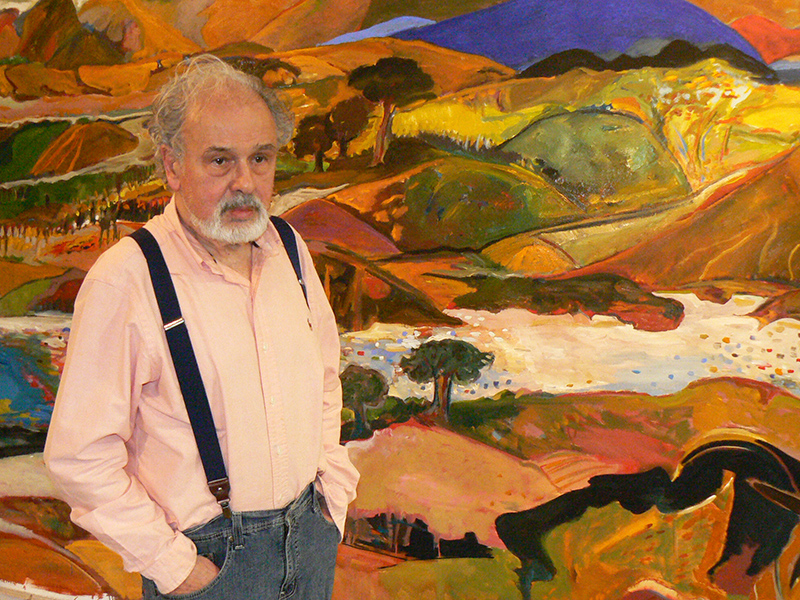

The creative force was so strong in Montreal artist Yehouda Chaki that he did not allow a degenerative illness to stop him from painting the brilliantly coloured, large-scale scenes inspired by nature that were his signature.

Even in recent years, as Parkinson’s robbed him of his ability to walk and even talk, Chaki was determined to put brush to canvas to express his joy at life.

Seventeen years after the diagnosis, the disease finally ended that creativity. The Greek-born Chaki died on Sept. 4 at age 84.

Odon Wagner, owner of the eponymous gallery in Toronto which held eight exhibitions of works by Chaki, described the artist as “without question” the most successful he had ever represented.

Admirers say he took his ever-worsening physical challenges in stride, and remember his energy and happy disposition before Parkinson’s diminished his ability to display that.

Former students speak of Chaki as a generous teacher and mentor. He was head of the painting and drawing department of the Saidye Bronfman Centre School of Fine Arts from 1967 to 1989.

Chaki exhibited internationally and his works are found in dozens of public and private collections in Canada and abroad, including the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), Concordia University, and Jerusalem city hall.

As he said in a 2016 interview with The CJN, “I’m 76 years old and I enjoy coming to the studio by six every morning to paint. I’ll be painting till the end, and my art is going to go on forever.”

That was the year the Jewish General Hospital unveiled his 14-foot-wide triptych entitled Mount Moriah, which hangs in the lobby of the heavily-trafficked Pavilion K.

Another major public work that will immortalize Chaki is The Four Seasons, painted on four glass panels mounted in 2010 in the pedestrian tunnel connecting Concordia’s John Molson School of Business to the metro. It was an adaptation of a canvas bought by the Royal Bank of Canada and hung in Place Ville-Marie in 1988. The year before, Congregation Shaar Hashomayim commissioned Chaki to create a huge tapestry celebrating its 145th anniversary.

Chaki also designed the bronze statue presented to the winners of Canada’s prestigious fiction award, the Giller Prize, from 1994 to 2004.

As Chaki’s mobility became limited, he used a scooter to navigate around his studio, a place he enjoyed bringing visitors to.

Chaki was born in Athens in December 1938. He never knew his grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins who were deported during the war and died in Auschwitz.

He, his parents and younger brother survived the Holocaust by assuming Greek Orthodox identities and hiding in the countryside with a Christian family. In 1945, Chaki and his family went to Israel and settled in Holon, near Tel Aviv.

After initial studies in that city, Chaki continued his education at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1960. There he met a woman from Montreal studying at the Sorbonne, Grace Aronoff, and immigrated with her to Canada in 1962. She is said to have been his muse and rock throughout their more than 60-year union.

Although best known for his vibrant expressionistic landscapes and lush still lifes evoking the Mediterranean environment of his youth, Chaki was deeply affected by the enormity of the Holocaust.

His first major work on that theme is the 1969 Express Train From Salonika to Auschwitz, acquired by Concordia’s Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery.

But his masterpiece, which lays bare an enduring grief, is the disturbing 1999 Mi Makir: A Search for the Missing, which was on exhibit at the MMFA from November 2020 to March 2021, in recognition of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

The Hebrew title refers to what Chaki heard constantly after the family relocated to Israel. Mi Makir, meaning “Do you know this person?” was the name of a daily radio broadcast of the messages of people appealing to the public for information on missing relatives.

The exhibition Mi Makir consisted of 117 unframed portraits of anguished people rendered in gloomy hues commemorating Chaki’s murdered relatives, as well as the millions of others who perished. Each work bears a number in the top left corner corresponding to an actual person who was exterminated in a Nazi camp.

On the floor in front of the paintings, there was a sculpture composed of piles of scattered books, reminiscent of the burnings of books by the Nazi regime. It also was intended to remind viewers of the ruins of Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues that were set on fire in Germany during Kristallnacht on the night of Nov. 9, 1938, just a month before Chaki was born.

Annette Wolfstein-Joseph, who was a student of Chaki’s at the Saidye Bronfman, recalled, “He had a presence that lit up the room and an infectious enthusiasm and sense of humour.”

Another student, Suzanne Côté, said, his “infectious love for the arts, his unwavering support and his remarkable ability to ignite creativity in others were qualities that have left an enduring mark on me.”

Besides his wife, Chaki is survived by their children Lisa and Adam, and his brother Moshe.