Before travelling to Buenos Aires, I associated Argentina with a few negative aspects of the city’s history – a location that harboured Nazi war criminals, the city where Israeli Mossad agents abducted Adolf Eichmann and the site of two terrorist bombings in the 1990s (the Israel Embassy and AMIA, the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina).

To gain a better understanding of Buenos Aires, I spent an afternoon touring the Jewish community and two days visiting popular tourist attractions such as La Boca, Plaza de Mayo, the Recoleta Cemetery and Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. The Jewish part of my tour was led by Ariela Bodner, a guide from Buenos Aires Jewish Tours. In just a few hours, I received a crash course on Argentinian Jewish history.

In 1813, a few years after Argentina began its war for independence from Spain, the president abolished the Inquisition and enforced policies that encouraged immigration. The country’s new hospitable environment inspired western European Jews to relocate to Buenos Aires.

The Jews who had lived in Argentina prior to this time were mostly Conversos or Marranos, Jews who converted to Christianity to avoid persecution but continued to practise Judaism secretly. It should be noted that modern historians are unable to identify any of the Conversos’ descendants living openly as Jews at the time of the signing of Argentina’s declaration of independence in 1816.

Thus, the newly arriving European Ashkenazi immigrants in the mid-19th century needed to establish a community. They worked together to create the Congregacion Israelita de la Republica Argentina (CIRA). These Jews eventually constructed a synagogue. The building was reconstructed in 1932 to meet the needs of the large number of Jews fleeing Europe.

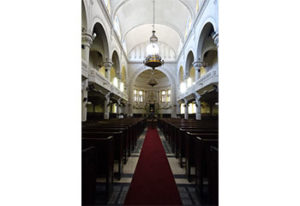

This Romanesque and Byzantine-style synagogue is a national historic monument and is located on Libertad Street, a block from the noteworthy Teatro Colón. It’s the oldest Jewish institution in Argentina and is oftentimes referred to as the Templo Libertad.

During the tour, I walked through the sanctuary and the modest museum that houses Jewish artifacts. I glanced upward at the vaulted ceiling that showcased the second level seating and a third level of arched stained glass windows. But the true focal point is the magnificent multi-storey Aron Kodesh.

In sharp contrast to the splendid sanctuary is the modest museum. The collection focuses on Jewish culture and has a tiny exhibit that sheds light on the Jewish Argentine cowboys (gauchos). These pioneers received assistance via the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), founded by Baron Maurice de Hirsch. They were enticed by the JCA to become farmers in Argentina’s countryside.

Today, the remaining vestiges of JCA’s colonies can be found about nine hours away at Moisés Ville, which has been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Most Jews today live in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area.

While walking in the Once district, we passed several synagogues. In one instance, we were instructed not to take any exterior photos. Security cameras targeted anyone who came close.

READ: MIAMI HAS PLENTY OF CULTURAL ATTRACTIONS

Bodner didn’t say much as we gazed down the street and watched the people go in and out of shops. Mezuzot were affixed to most of the textile storefronts. Kosher butcher shops and small synagogues were ubiquitous. Along our route, we came upon the Paso Synagogue, also known as the Great Temple Paso. Bodner spoke to the security guard and we were given access to the sanctuary. I admired the arches, the sculptured mouldings and the natural light shining through the strategically placed windows.

To remember the victims of the AMIA bombing, we walked past the site. Along the street, 85 trees stand as a living reminder to this tragedy. Since the building was closed for the day, we were unable to visit the courtyard of the reconstructed AMIA (the original building was destroyed in the 1994 bombing). Bodner told us that Israeli artist Yaacov Agam had created a colourful nine-column sculpture inside the AMIA courtyard as a symbol of hope.

A short distance away, I stood at the spot where the Israeli Embassy once stood. Today, a mini-park with 29 trees and several benches memorializes the casualties of the terrorist attack. Similar to the trees at the site of the AMIA bombing, each tree represents one of the victims killed in the attack.

Bodner shared her observations about the declining Jewish population. During the military dictatorships of 1976-83, approximately 2,000 Jews disappeared. The 1990s terrorist attacks raised issues regarding general safety. In 1998, two banks went bankrupt and created economic instability.

Decades after the AMIA bombing, even though the case lingers without any resolution, the controversy surrounding the death of the case’s chief investigator, federal prosecutor Alberto Nisman, remains in the news. One court recently declared his 2015 death a murder and, in December, another court indicted both former president Cristina Kirchner and former foreign minister Hector Timerman for allegedly covering up Iran’s possible role in the attack.

About a quarter of the country’s Jewish population lives in lower socio-economic conditions and looks to Jewish organizations for assistance. Fears associated with an insecure life have caused a noticeable percentage of Argentinian Zionists to emigrate to Israel. With a 40 per cent assimilation rate, a 40 per cent intermarriage rate and a low birth rate, the future growth for Buenos Aires Jewry seems bleak.

Despite these dismal statistics, Bodner said she feels the Jewish community remains vibrant and active. Buenos Aires has dozens of educational institutions that are attended by more than half of Jewish Argentine children, and Jewish community centres service the Jewish areas. The Organization for Rehabilitation Through Training (ORT) runs one of the best high schools in the city. The Joint Distribution Committee has lent a helping hand in organizing social programs to address the community’s needs.

While it is disturbing to hear about the Argentine Jewish community’s challenges, it was encouraging to learn about thriving schools and outreach efforts.

I recommend taking a few hours to discover Jewish life in Buenos Aires. While I didn’t experience any issues gaining access to the Jewish sites, I’ve been told by some people that a passport or driver’s licence is a necessity. To avoid disappointment, it’s best to arrange your visits in advance so security personnel don’t prevent your visit.