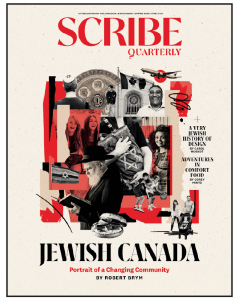

This piece originally appeared in the Fall 2024 edition of the quarterly magazine published by The Canadian Jewish News.

During a deadly, divisive war, everything is political. Especially a war that is livecast 24/7 around the world, on every screen and device.

Alongside the overwhelming nature of the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s subsequent onslaught in Gaza, the always-online era has pushed almost all of us into a politicized realm with a newfound intensity. Amid the flood of traumatic images and news spurring anger and grief, the performative nature of online culture has demanded we each know who is right, and that we always post the right take. This has always been true on the internet. But in the past year, it’s been all-encompassing.

This shift has taken on a heightened meaning for diaspora Jews. We have all been drawn into the obsessive political realm in ways I’ve never seen. Friends, old university colleagues and family who rarely so much as mentioned Israel before have spent the past year religiously watching, posting, weeping, and arguing almost daily. The diaspora may or may not be directly involved in the Israel-Palestine conflict, but we have been implicated by Israel’s designation of itself as the homeland for all Jewish people. With Jewish communities torn across ideological lines—Zionist and anti-Zionist, anti-ceasefire and pro-ceasefire—we have burned with grief, fear, passion, anger, and hatred. Some of us have drifted in the middle, conflicted or confused about what to believe. But we have posted anyway. It felt strange not to.

Feeling compelled to engage has been both organic—it feels wrong to be neutral in a situation of injustice—and amplified by multiple social pressures. Nearly all of us in the Canadian Jewish community have, or have family or friends with, deep emotional ties to the State of Israel. Many of us have felt coerced, implicitly or explicitly, into showing our unconditional support; at the very same time, we have faced mounting calls to disavow its actions, and even the idea of Israel itself.

There are extreme examples. A single Jewish mother I know who sympathizes with Palestinians has family who demanded she post her support of Israel on social media, threatening to distance themselves and cut off much-needed financial aid if she did not. Not posting at all about the issue was unacceptable. Her silence, to them, meant a betrayal of family and turning away from a homeland that was under terrorist attack. Their pressure, to her, meant she feels she has lost both her family and her ability to speak.

Anti-war Jews have had to defend their sentiments to other Jews, expected to furnish statistics and arguments on demand, both online and off. They have been asked for detailed answers to, “Well, what should Israel do? Let Hamas go?” Jews who back the current war have found themselves in precisely the same situation. Just about all of us could expect to be approached anytime, anywhere with huge questions. “Can you two tell me what the f— is going on?” one pal asked me and a Christian-Lebanese friend at a party in November. It wasn’t the last time we were asked for answers that night. I didn’t know WTF was going on myself.

Silence online risked signalling other things. There lurked an uncomfortable awareness that not talking or posting about the conflict might speak volumes in ways that non-Jews’ silence did not. To Zionist family members, it could mean betrayal. To friends or colleagues outraged by the mass killings of Palestinian children, it could mean implicit support of Israel’s bombs. And to them, conversely, any opposition to Israel from Jewish sources carried more weight.

Of course, online speech about Israel has always been incredibly fraught, but this has boiled over in new ways. Over the past year, far too many people—particularly people of colour, and particularly anyone who is Middle Eastern—have lost their jobs or been labelled antisemitic for criticizing Israel in any way. Zionist Jews (and sometimes those presumed to be Zionist because Jews) have also lost work, had public appearances cancelled, and been unceremoniously removed from theatre and gallery schedules.

That many of us have been forced to reckon with a disastrous 75-year-long conflict is not a bad thing. Social media has been rightfully lauded for giving a voice to those who wouldn’t normally have an outlet. And some of us in the diaspora have had the luxury of being apolitical for too long.

Much of this new engagement has been an awakening. It has been remarkable to see the diaspora in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, and other communities engage in political action this past year, some people for the first time. We have marched in protests, joined massive organizing chats, called our politicians, moved money to escaping Gazan families, and even flown to Israel and Palestine to provide medical assistance, help kibbutzim bring in their harvests, or just show up: a mass activation of people with many sympathies for different sides. Much of it has inspired me: the current conflict shook me awake from a long, inattentive hibernation. I have tried to update my ignorance by reading and learning. I have engaged in various ways, though nothing I did ever felt remotely enough. I have offended my dad, who volunteered in the Six-Day War, and even more thoroughly offended a distant relative who lives in an Israeli settlement. I have found community online with other anti-war Jews who live as far away as Texas.

What was troubling this past year were not these good faith, if often fraught, efforts. It was the way online culture—which is an awful lot of our culture these days—demanded our politics be instantly clear, instantly shareable, and consumable in tweets and TikToks. It was the lack of space for learning, for basic facts free of opinions, for uncertainty. Online seemed a place where only fully formed conclusions were welcome. This pressure risks producing a huge swath of content about the conflict that is either half-baked or regurgitated—tweets and posts whose tone and content are largely copied from others, so that we have something to say when we’re not sure what to say.

Without enough spaces for expressing still-inchoate thoughts, for seeking complex analysis (and cited sources), for showing the embarrassing gaps in your knowledge without being shamed for them, awakening into politics can never involve the deep education and mature reckoning that it should.

I have become a different person, online and off. In person, I have conversations with people whose views are far different than mine and have felt open to hearing them. Online, those same views have filled me with disgust. The uncompromising all-caps opinions of social media have admittedly become comfort food in a nonsensical world. I feel my tangled, contradictory thoughts smooth out against the solid online edifice of declarations, callouts, and rage. These days, I try to stay aware of my reactions—the way I seek out the self-righteousness of social media most when I’ve been torn apart by a new image of the warzone, when I feel the most helpless. I try to notice when I’m scrolling to make myself feel better, not to learn or discover anything new. And I remind myself that, in those moments, I don’t need to add my voice to the din.

Sarah Barmak is a journalist and author based in Toronto.