Think about the last time you watched an NBA game. Now try to picture someone in the stands waving a sign that says “Free Palestine”. Or wearing a MAGA hat. Or protesting the ongoing genocide of Uyghurs in China, or decrying last year’s ethnic cleansing in Sudan, or making any kind of comment on any kind of political event whatsoever.

You can’t. Because most major basketball arenas—as well as most teams—don’t allow them.

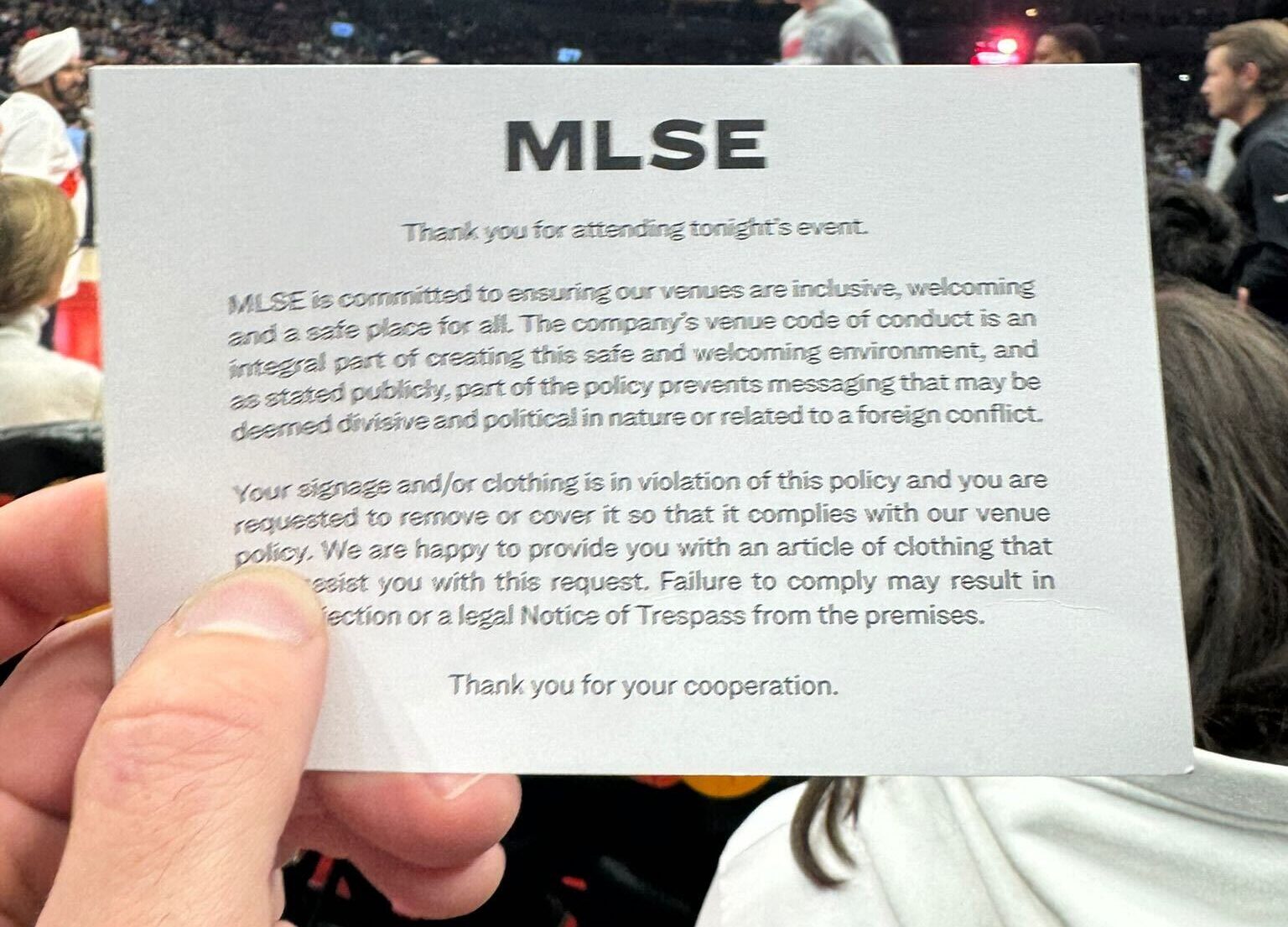

Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment (MLSE) is no exception. According to their code of conduct, they prohibit “signs, symbols, images, flags, clothing, banners that may be considered vulgar, discriminatory, disrespectful, political or a tool to be used for incitement or protest.” In late February, a Jewish lawyer named Gary Grill inadvertently tested this rule when he wore a black hoodie with the words “Free Our Hostages” and a Star of David underneath to a Toronto Raptors basketball game at Scotiabank Arena, which is also the home of the NHL Maple Leafs.

Grill told The CJN Daily host Ellin Bessner that he did not know about the arena’s ban on political messages. A security guard saw Grill, knew the rules, and gave him a choice: take off the hoodie or leave. So Grill left. Then, instead of hiding the fact that he ignorantly wore a political message to an arena that disallows political messages, Grill—and his seatmate at the game, Leora Shemesh, who is a vice-president at the Abraham Global Peace Initiative, whose campaigns are frequently highlighted in Postmedia publications like the National Post and Toronto Sun—doubled down and went public, making a big splash and giving right-wing public figures something to tweet about on an otherwise slow news day.

On March 5, 2024, a couple weeks after the silly incident, MLSE officially added a new line to their code of conduct, prohibiting “displaying signs, symbols, images or messaging that are deemed to be political and divisive in nature or related to a foreign conflict.”

Kudos to Grill and Shemesh for getting a corporation to change part of its legalese that no fan reads anyway. I would argue this whole debacle was not only unnecessary, but a paltry solution to an incident that makes Jews look significantly worse in the public eye.

First, let’s address the rule itself. Grill and Shemesh openly disagree that “Free Our Hostages” is a political message. To which I’d argue: Come on.

Shemesh told The CJN Daily that the arena security guard “actually couldn’t articulate what it was about the message that fell under the umbrella of this policy. He never really explained it all that well.”

OK, Ms. Shemesh. I will explain it for you.

There is a war going on between Israel and Hamas. Wars are, by definition, political. (MLSE’s new wording specifies “foreign conflicts”, as if there has ever, in the history of the world, been a foreign conflict that is apolitical.) The 130 remaining Israeli hostages are tragically, inextricably implicated as part of that war. The bold-font, all-caps, yellow-on-black demand to free them implies you have taken a side in that war. And in this war, not everyone is on the same side. There are millions of people out there, including many in Toronto—and perhaps many who attended that same Toronto Raptors game—who believe that the Hamas terrorists who brutally kidnapped, raped and murdered more than 1,400 innocent Israelis are not, in fact, as bad as the Israeli army that has killed more than 30,000 Gazans, mostly civilian women and children. And if one of your fellow Raptors fans sees your hoodie—and it, for lack of a better word, triggers them—then it can cause a confrontation or discomfort or any other strife that MLSE would simply rather avoid. So they made a rule: no political messages.

But enough about rules: onto point number two. I obviously do not work for MLSE. I work here, at The Canadian Jewish News, where we cover outrage and protests and antisemitism every day. Sometimes, Jewish Canadians are indeed being unjustly targeted by antisemitism, often veiled as anti-Zionism, as illiberal far-left activists have taken an increasingly aggressive tone in cancelling Jewish and Israeli artists, athletes and student groups, targeting Jewish businesses whose links to Israel are tenuous at best, spewing guilt-by-association at any institution (often universities) who associate with some other institution that has invested in Lockheed Martin which supplies weapons to Israel or something. It’s exhausting. But it happens.

Other times, however, Jews are not actually being unjustly targeted by antisemitism. Sometimes they are looking for a fight. Sometimes they are playing the victim card. Sometimes they are putting up pro-Israel posters in a public green space that does not allow posters and getting angry when they’re taken down. Sometimes they buy courtside seats to a Utah Jazz game for the explicit purpose of picking a fight with Kyrie Irving, bringing signs that are, again, explicitly not allowed in an NBA arena—then gleefully complaining to the media when they get kicked out.

Do you see any other distracting signs courtside? Do you see any other posters on those poles in the park? Do you see any #FreePalestine hoodies at the Raptors game? No? Then what makes you so special, that you can break the rules, then complain when you’re caught?

Such is my underlying discomfort: in the parlance of Jewish media, this is not good for the Jews. Too many non-Jewish people whose thoughts about Jews range from “casually antisemitic” to “outright hatred” already think we’re privileged, pedantic, rich and love to complain. How does “Two Jewish lawyers getting kicked out of a Toronto Raptors game” (average ticket price: $168) help dampen any of those assumptions? How does this further our cause for actual justice and open dialogue? How does this help sway public opinion to push governments to really, truly, “free our hostages”?

How does this do anything other than get you media coverage?

Back on The CJN Daily, the lawyers made the point that the NBA is already political, and players themselves wear, for example, Black Lives Matter (BLM) shirts during games. (Others have made this point too—ironically, when criticizing the NBA from the far left for being too pro-Israel.)

But why stop at BLM? The league’s only Israeli player, Deni Avdija of the Washington Wizards, has been vocal on social media about supporting his home country since Oct. 7. Enes “Freedom” Kanter, until recently a Boston Celtic, won’t stop tweeting about human rights abuses by China and Turkey. The Orlando Magic’s Jonathan Isaac is an outspoken right-winger who loudly refused the COVID vaccine, spoke at the ReAwaken America Tour (a Christian nationalist event filled with apocalyptic evangelism and conspiracy theories) and half-jokingly tweets about wearing Donald Trump’s $399 sneakers on the court.

And you know what? That’s fine! All of it! Because NBA players are celebrities. They have massive global audiences and can advocate for whatever causes matter to them, from PETA to Palestine. Don’t like it? Boo them.

None of that affects MLSE’s attempts to depoliticize the fan experience. If they swing open those floodgates, you might have Joe Israel in a “Free Our Hostages” hoodie sitting next to Joe Gaza with a “From the River to the Sea” T-shirt. Would they get into a fistfight? Or would they discover unexpected friendship and bond over celebrating a Scottie Barnes triple-double? We can never know, because MLSE doesn’t want to risk it. Frankly, neither do I.

Michael Fraiman is the director of podcasts for The Canadian Jewish News—and occasional columnist sharing his independent opinion.

Author

Michael is currently the director of The CJN's podcast network, which has accumulated more than 2 million downloads since its launch in May 2021. Since joining The CJN in 2018 as an editor, he has reported on Canadian Jewish art, pop culture, international travel and national politics. He lives in Niagara Falls, Ont., where he sits on the board of the Niagara Falls Public Library.

View all posts