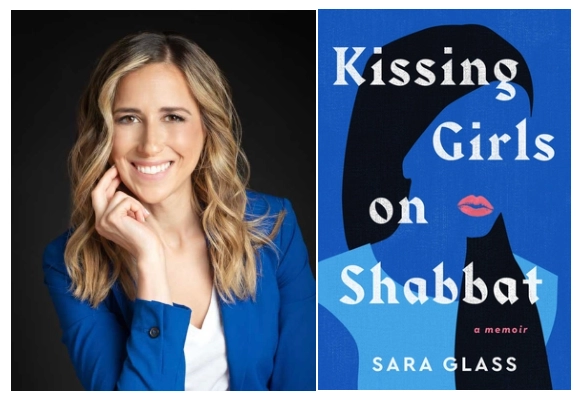

Kissing Girls on Shabbat

Sara Glass

(Atria/Simon & Schuster)

Whenever one speaks of the strides made towards LGBTQ acceptance, there is an asterisk needed, and I don’t mean the one that sometimes accompanies the acronym as an inclusivity gesture towards additional subcategories. I mean the bit about how these days, it’s no big deal if you’re gay, unless you happen to come from a traditionalist community, in which case yeah, still a whole thing, still a possible source of ostracizing or worse.

It can be tempting, contemplating all this from the perspective of someone who isn’t religious, to say, takes all kinds, and land on a kind of relativist position where you figure, this is what works for this community, who am I to judge? That position becomes harder to sustain when you hear testimony from people who are or were in such environments, and for whom mandatory heterosexual marriage with a mandate to be fruitful and multiply really, really doesn’t work.

Sara Glass is one such person. In her new memoir, Kissing Girls on Shabbat, Glass describes growing up in Brooklyn (with stints in Toronto and Jerusalem) as a member of the Gur Hasidic community—strict even by Hasidic standards—only to realize something about herself that I believe the title makes clear. “All love, except the love of God, was suspect, but one kind of love was singled out for extra damnation: loving someone of your own sex.” Where did this leave Glass, whose exclusive attraction to women was clear to her from a young age?

At 19, Glass was already “terrified of becoming one of those ‘older singles’ I’d heard gossiped about throughout my youth.” In her community, matchmaking that she herself likens to Fiddler on the Roof is the norm, along with an expectation that after a date or two, it’s time to start planning the wedding. She’s in the throes of puppy love with a young woman named Dassa who is not her first girlfriend, but it’s all very covert, and all must stop in a matter of days because there is Yossi and he is from a nice family and “find me a find, catch me a catch” and all that.

When Yossi makes his first appearance, and it’s clear he sees something in Glass, and was also really into gender segregation purity stuff, I wondered if maybe it would turn out that he was inclined like a certain cinematic Yossi, and hoped for her sake that this would be the case. That they could somehow pop out some kids but otherwise keep things companionate and each do their own thing discreetly, on the side.

‘Twas not to be.

***

It can be difficult to parse what’s Yossi being a bad husband and what’s merely evidence that this marriage was doomed from the start. “For my 24th birthday,” she writes, “Yossi bought me a toaster oven and a bread machine. It was confirmation of all that I had already known. To him, I was not a woman. I was a vagina who could cook.”

Once he has agreed to her request for a divorce—hard-won, in this world, and in this situation specifically—he calls her therapist to request that Glass sleep with him one last time, since he’s not sure when he will next get to have sex. Men!

Yossi’s complaint when they did go to counselling, that she was unenthusiastic about sex, basically, could be interpreted as sexist entitlement, or as the understandable reaction of a spouse who never stood a chance for reasons outside his control. I will not share the exact terms, because this would keep me from having a chance to quote the eerily applicable Victoria Wood song lyric: “I was 33 when it dawned on me that girls could move as well.” I suppose I’d classify it as both.

The book has darkly funny moments, including the “toaster oven” part. Glass’s first real encounter with the outside world is as a social work graduate student in New Jersey, at which point she is already married and the mother of a newborn. She sees a student group flyer about the female orgasm and doesn’t know what to make of it. “I figured that orgasm must be one of those popular culture references to which I was always oblivious, like Dancing with the Stars.”

Kissing Girls on Shabbat is an important testimony, an LGBTQ memoir, a story of family mental health crises: alcoholism, disordered eating, and suicide all make appearances. The story nevertheless opens—understandably, from a publishing perspective—on an erotic note, of the sort one would expect to be, how to put this… of disproportionate interest to heterosexual men.

There are lines like, “She bent her head, chestnut hair spilling over my chest as her lips burned a path of desire and shame down my body.” There’s a scene where she and Dassa, her also-Hasidic lover, sneak off into a Victoria’s Secret dressing room to try on the skimpier wares for each other’s arousal. I’m not saying this isn’t something college-age lesbians ever do, and it makes sense in the context of the plot, but… anyway.

A forbidden-fruit religious angle makes what might otherwise be an everyday story of hooking up all that much more titillating. Glass writes, of herself and Dassa, “On the outside, we looked just like the other college-aged Orthodox Jewish young women in Borough Park.” It is far steamier that they have something going on behind closed doors than that whichever hipster-looking Brooklyn women are doing the same. So you sort of think you’ll be reading a story about the beneath-the-surface passions of the pious and repressed. Instead it’s more of a conventional trauma-filled memoir, one as much about coming out as getting out. With emphasis on the get.

But man does it sound rough to be gay and Hasidic. (Cue the angry emails to me from the happy gay Hasids.) The subject matter itself is not new, and was first introduced to me personally from the 2001 film Trembling Before G-d, not long after its release. I remember some line in the movie where someone was trying to convey the difference between a straight person needing to have sex with an opposite-sex spouse not of their choosing, and finding yourself gay and in that boat. The gist was that while people of all sorts may chafe at a sexually restrictive environment, some things really are a bridge too far.

Indeed, in Kissing Girls on Shabbat can be difficult to disentangle—not that it needs untangling—what’s the stifling nature of an ultra-religious lifestyle (especially but not exclusively for women) and what’s specific to being closeted in such a community.

The most horrific story Glass shares is of her second time giving birth, wherein her husband’s dithering about how a rabbi has to give the go-ahead to labour-inducing medication causes her to give birth once the epidural has worn off. There are a lot of memoirs and personal essays these days about disappointing boyfriends and husbands, a lot of divorce memoirs specifically, but this, this is a taker of cake.

There is a scene in which a therapist “very gently asked” Glass, at this point with her second husband, ‘Have you ever wanted to have sex with a man?'” (Emphasis in the original.)

Glass writes that she “could not believe that I had never asked myself that question before. ‘I guess I never really thought about it in those terms,’ I admitted. ‘That’s a really good question.'”

But all the heterosexuality in the world wouldn’t make a woman not want to throttle a man whose interpretation of religion meant an avoidably torturous childbirth; who felt that observing Shabbat was more important than going to the hospital for a miscarriage; who required rabbis be consulted about when contraception was permissible; or who believed—as her then-husband evidently did—that the days of her cycle when a woman is considered impure for the purposes of sexual relations, he should be cold to her in daily life as well. It all sounds terrible! Even for a woman who was into dudes! And then that much worse, and bad in a bunch of different ways, for one who is not.

***

That a naive teenage Glass marries a man in her community is expected. What’s more surprising, and disturbing, is how after that marriage, even once she is no longer a strictly practising Hasid, and is initiated in the ways of the wider world, she feels she must try to date men and find a new husband. At first I wasn’t quite following. She’s not bisexual (though this is a term she uses a couple times, when testing waters, before coming out as a lesbian), nor someone in any real sense exploring her sexuality. Watching a straight sex scene on television, she observes, “My body, left to its own devices, would never react that way to a man.” Finally having sex with a woman (she had previously just fooled around with them) makes clear what was already pretty clear: “I was gay! I was 32 years old, and I finally knew. One million percent. I was gay.”

But her divorce contract mandates that she raise her children according to Jewish law, which means finding a new Jewish husband or risk losing custody. That, plus financial desperation, lead her to push past her lack of excitement over the male form. The Hasidic community she escaped from was so rigid in its ways that it required a pit stop marriage to a man who was more modern in his Orthodoxy.

Glass is clear that it wasn’t all bad in her community of origin, and speaks to the importance of family bonds. But there’s no ambiguity about the problems for people born gay into such communities. (And yes, for all the talk, in hyper-progressive circles, of how everyone’s a little bit sexually fluid, or at least all women are, some people really do swing fully one way or the other.)

It’s not just Glass who’s harmed by an inability to live as an out lesbian, but the children being raised in unions destined to fail, as well as the men who marry women they imagine are at least mildly interested in having sex with them. While Glass doesn’t really do this, nor do I blame her, it’s hard not to think, too, of the men—and more generally, the husbands and wives left behind in such cases.

Yes, a gay adult might choose to prioritize their interpretation of piety over a desire for sexual or romantic connection. (Catholic priests have been known to do this, to mixed results.) But if you’re a teenager told your options are marriage or being alienated from everyone you know and love, what choice do you have?

***

Kissing GIrls on Shabbat ends with Glass at last free to be who she is, confident in the custody of her children, and extricated from her second marriage. There’s not much about precisely where she’s landed ideologically, beyond that it’s a place more liberal than where she’d started out, but there are clues. Having at last earned her doctorate, she recalls attending a 2022 conference on Zoom, wherein a Black psychotherapist and sex worker nursed her baby while lecturing. This set forth, in Glass, an epiphany about how “Maybe, just maybe, the entire psychotherapy arena had been colonized by white men from decades ago, men who did not deserve to determine the extent of my own freedom.” This shift to a discussion of whiteness feels a bit random, as if it jumped in from another memoir, or a feminist memoir template.

That said, earlier in the book, a passage where Glass recalls an interaction with a police officer after she’d crashed her car has a footnote leading to an aside about how much worse this would have been if she were a person of colour, complete with a link to an antiracism organization. She’s not wrong about racism manifesting itself in this way, but it reads as a complete non sequitur. As this is the book’s sole footnote, its presence is either a clumsy editorial decision, or, if author-driven, as a nod to Glass’s current membership in the secular, progressive world. One where a key text has become a book like White Women: Everything You Already Know About Your Own Racism and How to do Better, rather than the Talmud.

Other potentially politically-charged topics do not get the same treatment whiteness does. I’m thinking in particular of Glass’s speculation about how Dassa might be finding things with her own husband, where they now live, “in the desert settlement outside Tel Aviv.” What… kind of settlement are we talking? Here there is no footnote, and frankly nor should there be because not every story needs to be about everything. From the sound of things, Dassa has enough to deal with as it is.

For more original Jewish culture commentary from Phoebe Maltz Bovy subscribe to the free Bonjour Chai newsletter on Substack.

The CJN’s senior editor Phoebe Maltz Bovy can be reached at [email protected], not to mention @phoebebovy on Bluesky, and @bovymaltz on X. She is also on The CJN’s weekly podcast Bonjour Chai.

Author

Phoebe is the opinion editor for The Canadian Jewish News and a contributor editor of The CJN's Scribe Quarterly print magazine. She is also a contributor columnist for the Globe and Mail, co-host of the podcast Feminine Chaos with Kat Rosenfield, and the author of the book The Perils of “Privilege”. Her second book, about straight women, will be published with Penguin Random House Canada. Follow her on Bluesky @phoebebovy.bsky.social and X @bovymaltz.

View all posts