The first time an adult spoke about sex to Jacob (not his real name), he was 22, and engaged. In the lead-up to his wedding, he and his rabbi met privately a half a dozen or so times. Their conversations, meant to prepare Jacob for the wedding night and the physical aspect of his soon-to-be marriage, were mostly textually based, examining “sex from a Jewish perspective.” His rabbi emphasized “what’s allowed and what’s not” in Jewish law, like the finer points of the laws that prohibit a husband and wife from touching while she menstruates.

Jacob, then a virgin, wasn’t a total neophyte on the subject of sex. “Like any kid, you just kind of figure it out,” he says. But his rabbi, who’s affiliated with a large Orthodox synagogue in Toronto and is, in Jacob’s view, relatively liberal in his approach (“he wasn’t embarrassed to say words like ‘penis’ or ‘cunnilingus’”), dispelled the myth that Judaism values sex solely for procreation. “We looked at how sex can be used to elevate a marriage,” Jacob, now 31, explains.

READ: THE TOP JEWISH BABY NAMES OF 2017

The sessions with his rabbi constituted what Orthodox Jews call a chatan (groom) class – a practice conducted with varying degrees of explicitness and dogma, depending on one’s level of piety. For a woman, there’s the corresponding kallah (bride) class, taught by the rabbi’s wife or another teacher.

The custom underscores the extent to which Orthodox Judaism treats sex as a sacred, tightly prescribed act, limited to the boundaries of (heterosexual) marriage and intrinsically bound to ritual.

Of course, the so-called Jewish perspective on sex has another, markedly different face. For decades, Jewish artists in North America have been churning out Jewish characters as neurotic as they are lascivious. Take Alexander Portnoy, a character in Philip Roth’s seminal 1969 novel, Portnoy’s Complaint. According to the book’s preface, Portnoy is afflicted with a “disorder,” in which “strongly felt ethical… impulses are perpetually warring with extreme sexual longings, often of a perverse nature.”

Or take Hannah Horvath from Lena Dunham’s HBO series Girls, a character for whom sex, no matter how unsatisfying or degrading, is the vehicle by which one discovers herself. There are the libertine characters in Mordecai Richler and Leonard Cohen’s novels and in Woody Allen’s films and, more recently, Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson’s show Broad City, whose protagonists pursue sexual encounters and self-abuse with the same abandon they apply to discussing their use of anti-depressants.

The over-sexed and self-obsessed American (read: secular) Jew is a trope that’s long prevailed.

With attitudes toward sex in the Jewish consciousness occupying two such extreme poles – one that firmly constrains it and the other that’s pathologically preoccupied with it – one wonders: does Judaism – do Jews – have an unhealthy relationship with sex?

ϖ

The front lawn of Malka’s house, at the corner of a wide suburban cul-de-sac, is strewn with plastic children’s toys. Wearing a sheitel and a long, modest shirt and skirt, she is amiable and petite. As she makes coffee in the kitchen, she confesses how happy she is to once again indulge in the beverage she gave up during her most recent pregnancy – her fifth.

In a dining room lined with books, Malka (also not her real name) – a certified sex therapist, former kallah instructor and a high school teacher at a religious girls’ school – explains that she and her husband identify as somewhere between modern and “more right-wing Orthodox.” Her clients, however, range from ultra-Orthodox to unaffiliated Jews, as well as non-Jews. What’s fascinating, she reports excitedly, is that regardless of their background, her clients’ sexual issues are basically “the same across the board.”

‘in orthodox schools, beyond cursory information about anatomy and puberty, little information is given about sex’

She rattles off a list of the most common issues individuals and couples see her for: woman experiencing physical pain during sex, often a result of a pelvic floor issue; premature ejaculation or erectile dysfunction for the man; a lack of desire, pleasure or the ability to orgasm on the part of the woman; and “couples who say they have sex problems, but actually just have a horrible marriage.”

Malka’s quick to stress that the Orthodox community can’t be painted with one brush, as each subset approaches sex differently. But she acknowledges that a religious upbringing can serve as both an obstacle and a boon when problems with sex arise.

“If (a couple) had good chatan and kallah teachers, their issues get dealt with much earlier in the game than couples who don’t know who to turn to,” she says.

“Judaism says the marriage should be consummated on the wedding night, or soon after, so if something goes wrong in that first week, they usually call their teacher or rabbi, who can help assess if there’s a medical problem, or if they just need some time.”

On the other hand, she’s seen the problems that can arise when chatan and kallah teachers haven’t been properly trained. “You get these horribly damaged, dysfunctional couples,” she says.

She concedes that it’s also not uncommon for those growing up in the Orthodox world to associate sex with guilt and shame.

“It really depends on who your rabbi is. With masturbation, say, some rabbis understand this is what teen boys do. They normalize it, telling students, ‘you’re not supposed to do it, but if it happens, don’t worry.’ Other guys are meant to feel guilty and disgusting … like they’re going to burn in hell. They’ll bring that shame into their marriages,” she says.

READ: WILL THE JEWISH COMMUNITY INCREASINGLY REFLECT AN ORTHODOX AGENDA?

As for sex education in the Orthodox school system, Malka says that beyond cursory information about anatomy and puberty, little information is given about sex (Rabbi Seth Grauer, head of school of the Orthodox Bnei Akiva Schools, asserts that they do follow the Ontario curriculum, but take an “integrated” approach).

“The way it works is you’ll have teachers who are close with their students,” Malka says. “I have girls who will come to me with questions (about sex) and I’ll talk to them after class one-on-one, or in a group of three or four.” She notes that the intimate nature of these discussions is meant to reinforce the idea, which comes from the Torah, that sex is “kadosh – this means holy, but also separate… beautiful and important, but something to be kept private.” She says it used to be that sex education was transmitted from mother to daughter. Nowadays, “people aren’t as comfortable with that.”

ϖ

Judy Greene is a New York-based sex educator and the director of admissions for Ramah Israel’s teen programs. She’s taught courses on Jewish sexual ethics at Camp Ramah in New England and at various Hillel branches on American college campuses. She co-created a curriculum called Sacred Choices, published by the Union for Reform Judaism and delivered to Jewish middle and high school students. She says Jewish day schools don’t have a great track record when it comes to sex education, which, in her view, is inseparable from sexual ethics.

“I find lately a lot of (Jewish) kids are very sheltered,” she says. At some of the day schools she’s taught at, parents ask to see the lesson plans beforehand. She recently brought up masturbation with Grade 9 students and was struck by the fact that “some of the kids still thought they weren’t supposed to do it, and some of their parents are still upset I brought it up.” She laughs, “When I teach at summer camp and say, ‘Let’s talk about masturbation, everyone is like, ‘Yeah!’ Camp feels safe; it’s the greatest place to talk about – and even try – some of these things.”

Her classes draw on biblical and Talmudic sources, and her approach is largely influenced by Conservative Judaism. She starts her classes off by saying that whatever she’s about to say applies to any relationship, whether heterosexual or LGBTQ.

She also says that, with people increasingly getting married later in life, or not at all, the notion of “pre-marital sex,” which classical Jewish texts don’t condone, is somewhat antiquated.

“Conservative Judaism feels you’ll be with people outside of marriage. .. things are open to interpretation. We’ve been interpreting the Bible on everything else,” she says, adding that the idea of what constitutes sex in Judaism hasn’t been consistent.

‘i saw in the texts an obsessive attention to sexuality that seemed… linked to an obsessiveness about being Jewish’

“In biblical times, if you had oral sex, you were still a virgin. In Talmudic times, ‘safe’ sex was anal sex,” she says.

The bottom line, for her, is that no matter what you do, Judaism wants you to treat the other person respectfully.

“Sex in Judaism isn’t about the sex, it’s about the relationship,” she says. “I talk to kids about how you respect (a sexual partner). I emphasize self-esteem.” She tells campers who want to have oral sex “to practice” for when they have a boyfriend or girlfriend: “If you can’t talk about it with the other person, you shouldn’t be doing it.”

She concedes that a one-night stand is probably not considered “a respectful relationship” in Judaism, but one that’s “about self-gratification.” And if both people consent to a mutually respectful, casual sexual relationship? Greene says, “That’s a good question. I don’t have an answer… The bottom line is respect.”

ϖ

How does one square the notion of sex as something worthy of a kind reverence with the stereotype of the libidinous, navel-gazing Jew, for whom sex is indisputably about the self, not the other – about gratification, escape and often, the simple fulfillment of curiosity?

Josh Lambert is a visiting professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Born and raised in Toronto, he’s the author of Unclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews and American Culture. While studying Jewish literature in graduate school, he says that he began to see in the texts, “an obsessive attention to sexuality that seems both very intense and somehow linked to an obsessiveness about being Jewish.” Intrigued, he started reading historical accounts about American obscenity trials and literature in the 1950s and ’60s.

“I’d read about Supreme Court decisions on this and the (cases) all had names like Rosen v. New York, Cohen v. California. I was like, ‘why is every single one (involving) a Jewish guy?’”

The more he researched, the more he found American Jews on the front lines of both the production and legal defence of explicit sexual materials. In the early 1900s, Jewish-run publishing houses, such as Grove Press, were the only ones willing to publish works – deemed obscene by other publishers – by the likes of James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner and Henry Miller.

‘sex in Allen and Roth consists of sex between Jewish men and non-Jewish women… It comes down to a fascination with assimilation’

Unclean Lips, which is based on Lambert’s dissertation, explores the various reasons why Jews often led this fight. For one, Jewish lawyers, themselves outsiders, may have viewed freedom of speech as a safeguard for voices on the margins. For another, they might have viewed the fight as a challenge to sexual anti-Semitism, which was prominent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “It was commonplace for Jews to be (seen as) sexual criminals… child molesters… that was the discourse,” Lambert says. He argues that Sigmund Freud, whose writings were regarded as scandalous in their day, aimed to combat sexual anti-Semitism by almost exclusively featuring Jewish patients, but striving to make their experiences seem “totally universal.”

Lambert says the modern paradigm of the self-loathing, sex-obsessed Jew likely emerged due to a number of factors. “It’s hard to generalize about this stuff. There might be a link between Woody Allen and Lena Dunham, but the two are also very different,” he says.

He notes that a lot of the sex portrayed in the oeuvre of artists like Allen and Roth consists of sex between Jewish men and non-Jewish women. “It’s about the tensions and excitements of sex with the other. It comes down to a fascination with assimilation and questions of identity, as played out through sexual metaphor,” he says.

Later, in the post-Ronald Reagan political landscape of the United States in the 1990s, Lambert says that the rise to prominence of evangelical Christian culture likely unsettled many Jews.

“Look at people like Larry David and Sarah Silverman. Their openness about sex is a way to refute that moral majority thing happening,” he says. Once it’s ubiquitous, the model starts to feed on itself. “By the time the Broad City girls are growing up, they look to older Jewish sources and see these intensely sexual things, and so they associate that with Jewish tradition.”

ϖ

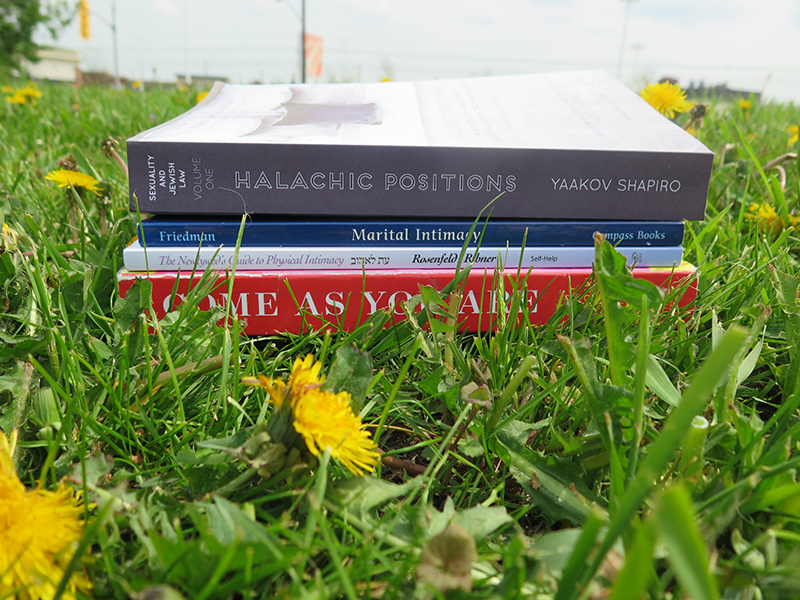

One of the books on Malka’s dining room table is A Newlywed’s Guide for Physical Intimacy, a manual for observant Jews written by Jennie Rosenfeld and Rabbi David Ribner, a Jerusalem-based, Orthodox sex therapist.

On the first page of the book, which contains surprisingly explicit descriptions of foreplay and intercourse, readers are instructed: “Your enjoyment as sexual partners is more than just physical… it is the glue that binds your marriage together.”

Over email, Rabbi Ribner says Judaism is fundamentally “a sex-positive religion.” Within the context of marriage, he writes, “couples are free to conduct themselves as they wish, provided that any sexual activity is mutually acceptable.”

Malka says it’s a common misconception that Judaism is only concerned with sex for procreation. In the Torah, the two mitzvot related to sex are to have children and that the husband must satisfy his wife’s sexual needs. Some rabbis will talk to future grooms about how to give a woman pleasure, to be gentle and listen to what she wants; some won’t, she says. She believes most of the laws exist to protect women, like the one stating a man can’t force his wife to have sex.

At times, however, “the patriarchy takes over.” Rabbinic law says a man can ask for a divorce if his wife refuses him sexually, and there are men, and religious leaders, who will, she says, “bastardize the law and guilt the woman into having sex.”

In cases like that, she stresses: “that guy is not just a bad Jew, he’s a bad person.”

While the Orthodox community still has a long way to go in terms of improving sex education and emphasizing the importance of mutual respect and communication between partners, the same can be said for everyone, Malka says, Jewish or not.

Both for religious Judaism and in Jewish artists’ frequent portrayal of secular Jews in the media, attitudes toward sex are far more complicated than they initially seem. In both realms, sex is hugely significant, its value and purpose far transcending the physical act itself. But whether elevated for its capacity to sanctify a marriage, or as an assertion of freedom in the face of discrimination, the role of sex in Judaism is, if not always healthy, at the very least, extremely vital.