This is the 20th in a series of opinion columns on the 2022 Ontario provincial election, written by Josh Lieblein for The CJN.

We usually to wait for an election to end before complaints about the unfairness of our voting system start rolling in. But with most observers predicting a done deal for the Ontario Progressive Conservatives, we get to ask a timeless question earlier than usual:

If the majority of provincial voters hate Doug Ford, how is he going to win?

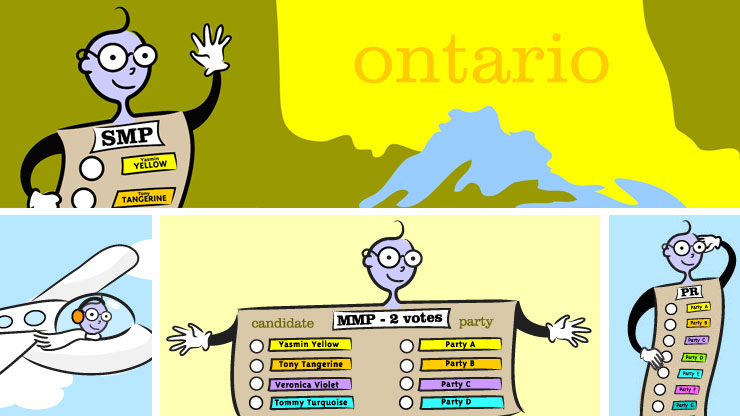

Efforts to modify the traditional first-past-the-post (FPTP) system—where the person with most votes wins, even if the majority don’t vote for that person—have typically been hampered by voters who don’t understand how other systems work, and by reports of legislative chaos and elections seemingly every other week in places where systems that are more “representative” are the law of the land.

Or, as some say in the Jewish community: “Wait: so you want to make our system more like Israel???”

That hasn’t stopped the opposition parties from trying to shake things up. Ontario Liberals want to replace FPTP with ranked ballots, where voters order their preferred candidates and if nobody gets 50 percent of the first choice votes, then the last place candidate drops off the ticket, and their second place votes are distributed to the other choices. This goes on until someone gets a majority.

(Ironically, it’s also how Doug Ford was elected leader of the Ontario PCs.)

New Democrats and Greens want a mixed member proportional system, where people would vote twice—once for their local representative, and once for candidates elected from a list, so that every party would have the same percentage of seats as the percentage of votes they receive. The two parties differ in who would be on the list of representatives, as the NDP would make sure they came from a predetermined party list, and the Greens want them to be from a randomly selected citizens assembly.

(For the record, Israel doesn’t have any of these systems. Over there, you vote once, for a party, and the seats are given in proportion to the percentage of votes each party got, to candidates in the order they appear on a list made by each party.)

If you’re confused, or wondering how anyone could defend any of these systems, I completely understand.

But instead of talking to a representative of a party who’s more interested in winning your vote than speaking to what they honestly feel, I managed to get someone who not only can defend voting reform, but can also speak to how we avoid the problems Israel has.

Justin Ling is one of Canada’s top investigative journalists. He’s usually busy digging into the abuses in our nation’s prison system, hosting a history of right-wing extremists on the CBC with his podcast The Flamethrowers, or getting piled on by guitarists who regularly downplay the horrors of communism. But he generously made some time to answer a few questions from me.

When I asked Justin why he thought Ontario’s system was in need of an overhaul, he made the point that elections should reflect the will of voters, and our system isn’t doing that.

“Only one-third of voters in Scarborough-Guildwood voted for Mitzie Hunter, yet she was elected to represent the riding,” he notes about one Liberal MPP in its smallest caucus ever. “Elections are frequently called early, minority governments last around two years on average, and it is virtually impossible for small parties to break through.”

So what sort of system does he think would work better and why? Justin says that as far as he’s concerned, anything’s better than we have now. “Northern Ireland just held elections with their single transferable vote system—meaning you vote for the candidate you want, but rank as many other choices as you please. Australia, too, just held elections under a similar instant runoff system.”

And when it comes to Israel’s problems, he thinks they can be worked around. “An electoral system can worsen existing political discord, but it doesn’t create it. Proportional representation can lead to a litany of parties entering parliament, causing chaos [but] you only need 3.25 percent of the votes to enter the Knesset. In Germany, that number is 5 percent.”

But then, as the case with many of the issues raised during this election, the solutions seem to involve more political will than our elected representatives have on hand. And that’s just one more consequence of minority rule.

Josh Lieblein can be reached at [email protected] for your response to Doorstep Postings.

Author

Josh Lieblein lives in Toronto. Read more of his writing at looniepolitics.com.

View all posts