At McGill University, where I am a graduate student in the physics department, I regularly witness anti-Israel vandalism on campus. Since the infamous encampment on McGill’s front lawn was dismantled a year ago, the vandals and activists usually keep to the front gate (with at least one exception), denied entry by McGill’s private security. Unfortunately, the security force doesn’t prevent student groups from being taken over by anti-Israel ideologues.

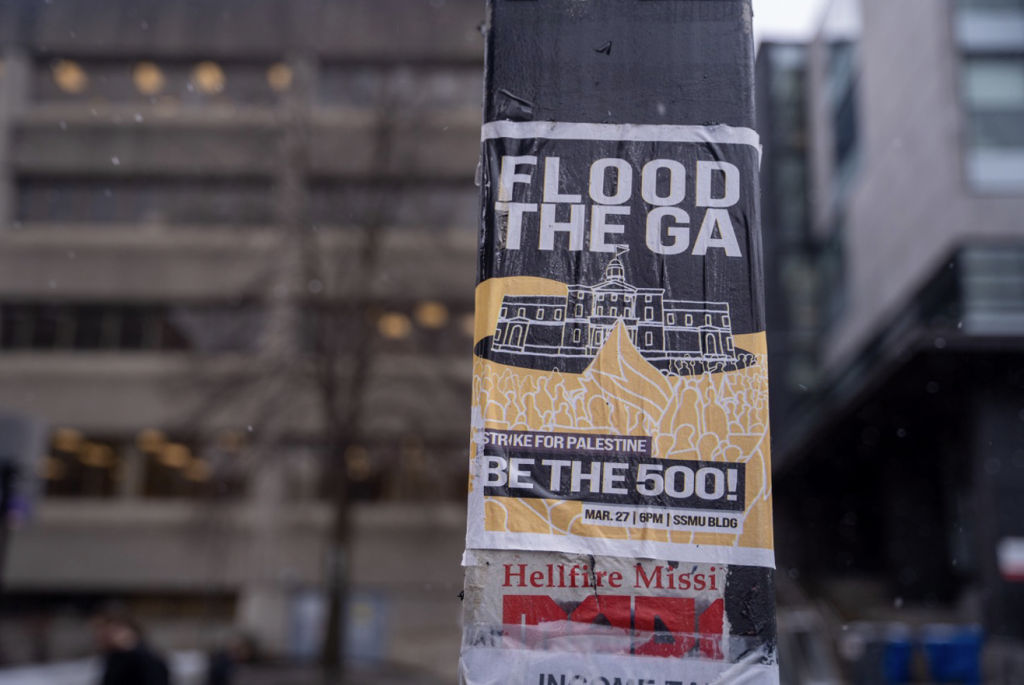

Large student groups tend to require low participation thresholds for quorum which make them very easy to commandeer. Just by showing up, tiny minorities of radicalized members can pass whatever motions they please. In this way, institutions are bent in allegiance to certain ideologies to which the majority of constituents may be ambivalent, or even find repugnant. I’ve seen this happen many times, most recently to the Student Society of McGill University (SSMU).

On April 7th, McGill began the process of severing its relationship with SSMU. McGill intends to terminate the contractual agreement which outlined responsibility to, for instance, collect fees from undergraduates, which could be distributed by SSMU to fund student clubs, initiatives, insurance, etc.—basic student union offerings that are ancillary to core university programming.

Why did McGill do this? SSMU held a strike vote in support of “Palestinian liberation” and, expressing a “desire for McGill to divest” from “companies linked to military actions in Gaza”. The vote passed and a strike was held spanning three days during which masked, keffiyeh-sporting students barricaded the entrances to lecture halls to prevent their peers from attending the courses they paid for. McGill is nullifying their agreement with SSMU because of these blockades and the vandalism implicitly supported by SSMU.

On the last day of the strike, protestors found their way into the Rutherford Physics Building, where they decided to barricade doors to an auditorium in which an eminent Jewish physics professor was lecturing. By chance, I was walking by as they rushed in through the main entrance to the doors, where they began to take formation. I asked them what they were intending to do, and they were quite clear about not letting their fellow students attend the lecture. I tried negotiating with them, but they would not yield. I told them they had no right to prevent their peers from attending their class but my words fell on deaf ears.

I asked them why they were doing this. They told me there’s an “ongoing genocide” and that “undergraduate students voted for a strike.” Does this mean the majority of undergraduate students wanted this? No, it does not.

For a student society purportedly representing over 24,000 undergraduates, quorum for a strike vote is met at only 500, or about 2%. Fewer than 700 students attended the general assembly to vote on the strike motion—less than 3%. For the strike to take place, though, a slightly higher barrier had to be overcome: an online ratification vote requiring at least 10% of the membership to participate. They managed to achieve this, with under 11% of the membership voting in favour and about 5% opposed—and 84% of the membership unresponsive.

This isn’t extraordinary. In 2023, Harvard’s graduate student union adopted motions to endorse BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) actions against Israel with a whopping 12% voter turnout and a 7.2% “majority” vote in favour. By comparison, voter turnout for US and Canadian federal elections is regularly over 60%.

Assuming the activists read and understood the bylaws constraining these institutions, they are savvy. They understand how they can leverage a tiny fraction of the membership to make the entire institution bow to their cause, thereby giving the illusion of consensus.

A similar thing happened to a population I know better. MGAPS is the McGill Graduate Association of Physics Students. Every physics graduate student at McGill—and there are about 180 of us—is necessarily a member of MGAPS. In early 2024, MGAPS published a “Statement on Palestine.” The document calls Israel an apartheid regime, states that Israeli actions in the Gaza Strip constitute genocide, and proclaims that MGAPS members agree with these statements. It also says, “physics graduate students voted nearly unanimously in favour” of publishing said statement. This is a complete lie. I was there—and most physics graduate students were not. Indeed, less than a quarter of us voted at all.

How can these motions pass if they’re supported by only a tiny minority of group members? Simple. Those are the rules. Only a minority of group members need to support the motions in order to see them passed. One should not assume consensus among members of a named group when it publishes a statement—even if it reads “a majority voted,” or “near unanimous,” or “78% agree.”

I don’t doubt there are more examples of large groups ascribing a belief to their membership when only a small fraction hold it. Reader beware: your group may be captured. If you find you’re not part of the supposed consensus, there may not be one.

Regan Ross is a graduate student at McGill.