Anti-Semitism, with the slurs and stereotypes that stem from it, is not a new concept. From the middle ages to present day, the types of anti-Semitism have changed dramatically, but it is no less prevalent today than it was 1,000 years ago. Likewise, Russia and the countries that made up the Former Soviet Union, are no exception to this.

However, in modern-day Russia, anti-Semitism is something that is really prevalent in everyday life. Recently, President Vladimir Putin suggested in a speech that Jews could have been the ones who manipulated the 2016 U.S. presidential election. He also stated that the election interference could have been done by Ukrainians or Tatars, or people with a Russian citizenship. His apparent insinuation that a Russian Jew is not really Russian sparked particular outrage amongst Jewish groups, reminding people of Russia’s long and notorious history with anti-Semitism.

History has shown that anti-Semitism has been a big part of the Russian-Jewish experience, and has affected many generations of Jews living within the Russian Empire.

READ: THE HOLIDAY WITH TEARS IN THE EYES

“Some scholars today argue that anti-Semitism is as old as human history, and as the Jewish people, but it’s quite clear that in different times, anti-Semitism meant different things,” said Queen’s University Jewish history professor Vassili Schedrin. Though the prejudice against Jews has been around for centuries, the term “anti-Semitism” only became popular in 1879, when it was coined by German agitator Wilhelm Marr.

According to Schedrin, anti-Semitism during the middle ages was based more on the religion itself, often referred to as “judeo-phobia.” Jews typically lived separately from the rest of society, and were very isolated. In medieval times, Jews lived in exile, or diaspora, and formed closed autonomous communities and as a result, outsiders were suspicious of this group of people because of their different behaviour.

“In medieval times, most of the people’s lives were framed by religion, so you cannot exist beyond this religious infrastructure and religious thought. The Jewish religious world was separate,” said Schedrin. “It was incomprehensible to others, so the popular perception of the Jews was based on the idea that Jews and Judaism were essentially anti-Christian.”

However, because of several writings done by church fathers, Schedrin says that Jews were considered to be an integral component of “the last days,” and were necessary for the second coming of the messiah. Therefore, on the basis of the church doctrine, Jews were to be tolerated. “This toleration did not mean their integration into Christian society, because the religious difference was such a barrier at that time, you can’t overcome it until you convert,” said Schedrin.

Throughout the centuries, as more countries in western Europe started to grant emancipation to their Jewish populations, Jews were able to become more integrated into the overall society. Many thrived under this new system, and became very successful in all sorts of fields, allowing them to progress socially and economically. However, Schedrin said that a key distinction between western and eastern Europe is that emancipation was not granted to the Jews living in eastern Europe.

“Some European thinkers started to develop the idea that emancipation was a mistake, and led to the rise of the Jews and demise of Europeans, this is how they explained the ‘crisis,’” said Schedrin. “The emancipation violated and destroyed the balance – they are being dominated by the minor foreign element, which was the Jews.”

Later on, during the times of imperial Russian, the various czars did not give the Jews much freedom and required them to live in the Pale of Settlement, which included: modern-day Belarus; Lithuania; Moldova; much of Ukraine, eastern Latvia; eastern Poland; and the western border of Russia. This area existed, with varying borders, from 1791 to 1917, and was created by the Czarina Catherine the Great. For Jews, these years were plagued with pogroms, which were attacks on Jewish shtetls, as well as many other restrictions and problems that prevented them from rising up in society.

In the 1880s, Russia finally began to work on having a capitalist economy and the process of industrialization. “To create a capitalist economy, there are a lot of money-hungry projects, mainly for infrastructure, such as railway building. This was the largest, and fastest growing business in Russia until the First World War,” said Schedrin.

When the Russian Revolution came around in 1917 and overthrew Czar Nicholas II, effectively ending the Romanov family’s 300-year reign over the Russian empire, Jews were finally given the right to leave the Pale of Settlement and settle across Russia.

However, the persecution of Jews did not stop after the revolution, and in many ways, things got worse before the got better. Though Stalin promoted Yiddish culture and encouraged the proliferation of Yiddish plays and schools, anti-Semitism was still rampant in this time. Judaism, along with all other religions, was outlawed, and synagogues were destroyed. Stalin also ordered the murder of prominent Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels, and was also behind the anti-Semitism campaign known as the Doctor’s Plot, which accused a group of well-known Jewish doctors in Moscow of conspiring to assassinate Soviet leaders.

Even after Stalin’s death, Russian Jews were continuously persecuted. The Communist regime published anti-Semitic books and executed dozens of Jews in the 1960s and 1970s.

Interestingly, under the Communist regime, there was no official anti-Semitism, and in fact, if someone where to be caught being openly anti-Semitism, it would be considered as a criminal offence. In reality, however, this was not the case. Many different types of career paths were closed for Jews, and certain universities would not accept students merely because they had a Jewish last name. The same thing would happen with employers, as many did not hire people who had the word “Jew” written in their documents.

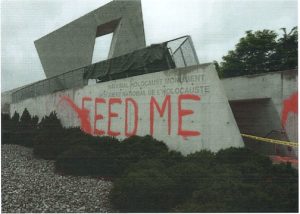

According to an annual study of contemporary anti-Semitism and racism done by the Kantor Centre at Tel Aviv University, found that in post-Soviet areas, particularly in Ukraine, there has been an increase “both in violence and all other types,” though they estimate that their actual numbers are higher, since many Jews do not report anti-Semitic incidents.

Across the rest of post-Soviet areas, there was a low average of cases, however “the attempts to exonerate and glorify nationalist leaders who actively cooperated with the German anti-Jewish policies of persecutions and murder during WWII, intensify due to the renewed nationalist aspirations in eastern Europe.”

Though the former Soviet Union is by no means the only place that has a long history of anti-Semitism, the effects of this prolonged history is still seen today in many people’s dialogues.