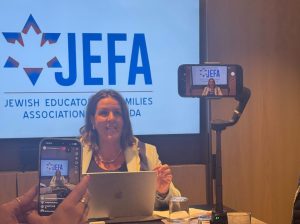

The verdict is in: identity politics is to blame for rising antisemitism in schools. At least, that was the conclusion of a report released last week by Jewish Educators and Families Association of Canada (JEFA).

What exactly does ‘identity politics’ mean? As I understand it, it is a criticism of the classical liberal theory that we should only see people as individuals, because that theory has failed in practice. Many today are more aware than ever of the role that group identity plays in life outcomes, regardless of individual characteristics.

Identity politics is a way to reckon with privilege. According to identity politics, privilege, not merit, is the ultimate social determinant. Therefore, we need to pay attention to which identities are more privileged than others so we can correct for it at both individual and societal levels.

Identity politics is best suited as a diagnostic tool, to call attention to the neglected role that identity plays in determining life outcomes. In its current iteration, though, it has become an alternative moral system.

This is how the JEFA report describes the impact of identity politics in schools: “These frameworks shift the focus of education from individual rights and merit to collective identity, power dynamics, and historical oppression. By emphasizing immutable traits such as race and ethnicity, they confer special status on certain groups of students while marginalizing others.”

So what does this mean for us as Jews, and the strategies we should adopt for combatting antisemitism?

Embracing identity politics can be tempting, but it has ultimately proven to be a race to the bottom. In a social framework that valorizes victimhood, people are incentivized to see themselves as oppressed, and to discriminate against supposed oppressors.

I am hardly the first person to make this claim. However, I do not think sufficient attention has been paid to this broader social context in our attempts to combat antisemitism. We are all aware that left-wing antisemitism is on the rise, but how is it connected to left-wing bigotry more generally?

For many years, I believed that the definition of left-wing antisemitism was using Jew as a synonym for an affluent white person. There are, of course, multiple issues with doing so: One, not all Jewish people are affluent. Two, not all Jewish people are white. And three, even if some Jews are affluent and white, we do not have the collective history of a wealthy group of white people.

Even though some people might look at the white, affluent subset of Jews and think of them as insiders to society, most Jewish people don’t feel like insiders. Hardly any of us feel the sense of safety and security from society that we assume other ‘insider’ groups (namely, well-off descendants of white Christian Europeans) take for granted.

I still stand by that analysis. But I realized that seeing Jews as affluent, white insiders does not amount to antisemitism on its own. What turns that false belief into antisemitism is the further belief that it’s permissible to discriminate against affluent, white insiders.

That comes from a certain modern left-wing mindset, which holds that privileged people do not deserve protection from discrimination. If anything, they deserve to be discriminated against–the privileged must be brought down to liberate the oppressed.

This contributes to antisemitism because, as my colleague Phoebe Maltz Bovy summed it up, the left is furious at Jews for “our unchosen roles as avatars for right-wing whiteness.”

This is the context in which antisemitism is on the rise. Although it by no means explains all of antisemitism today, I do believe it explains a significant portion of it.

Identity politics today is not about protecting all people from being improperly discriminated against because of their identity. Instead, the JEFA report shows, it has calcified into a hierarchical system in which some groups are always identified as victims and others as oppressors, and the statuses of groups are not subject to change.

The victimized groups will always be victims, the oppressor groups will always be oppressors, and the individual members of those groups will be treated accordingly.

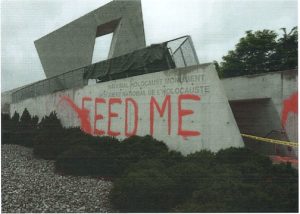

We might be tempted to play identity politics by de-emphasizing our privilege and playing up our historical oppression. Perhaps our favourite way of doing this is through Holocaust education. But in the context of today’s identity politics, we can see why that won’t work.

The fact that Jews were oppressed in the past does not automatically mean that we are victims now. People can understand that the Holocaust was wrong but deny its relevance for modern antisemitism.

The Jews who perished in the Holocaust—wherever they started out in life—were ultimately victims, oppressed members of society with no political agency. Today’s Jews, on the other hand, have been deemed oppressors. Our past as victims is irrelevant to our current privileged status. As long as we remain privileged, we do not need protection from discrimination.

The upshot of combatting antisemitism through Holocaust education also reveals the cynicism of identity politics. It implies that we only deserve protection from discrimination because of our history of oppression.

But the fact that we were victims in the past is not the reason why it’s wrong to discriminate against us now. It’s wrong now because it’s wrong to discriminate against anyone, regardless of the history of their group.

Identity politics cannot account for this simple truth, and so it fails to protect anyone that is not deemed sufficiently oppressed. According to JEFA, identity politics frameworks have led to discrimination against Christians, Hindus, Asians, and mixed-race students.

As JEFA co-founder Tamara Gottlieb put it, “This is systemic failure. This is not just a Jewish concern. It’s the canary in the coal mine. It’s a system that’s lost both its moral and academic purpose.”

If this problem affects more than just Jews, then we should not treat it as just a Jewish problem. Nor should we work alone as Jews to tackle it.

The way we need to respond is clear. We should not only attempt to address antisemitism directly. We must also address identity politics as a whole, and begin the work of articulating a new moral framework that can account for privilege while still respecting the individual, without reducing people to their group identities.

Alex Rose is a PhD student at the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology at the University of Toronto. He previously worked as a reporter for the Canadian Jewish News.