When I first met the wonderful American Jewish poet Marge Piercy, she asked me about Shavuot and paper cutting. Someone had sent her a piece of paper cut art and the gift evoked old memories of her grandmother’s holiday observances. We both had vague recollections of the association of the spring festival with the folk art form, but it was not an active part of either of our families’ Jewish traditions.

There is an undeniable human impulse to beautify – to adorn and embellish things that we hold dear. We take pleasure in decorating our home, outfitting our children and setting a lovely table. In my counter-culture phase, I thought of such activities as materialistic and superficial. But I’ve come to realize that investing energy and resources to make things aesthetically pleasing can be deeply spiritual. We lavish attention on what we value and love – not only physical things, but intangible ones, as well – so that our values become visible from the outside.

In Judaism, we call this hiddur mitzvah, the beautification of a commandment. We see this in action when we look at the practice of adding decorative components to things that are dryly pragmatic in nature – for example, a ketubah (marriage contract) or a mizrah, which is used to indicate the western direction of prayer.

READ: A VERY JEWISH COLLEGE CAMPUS GUIDE

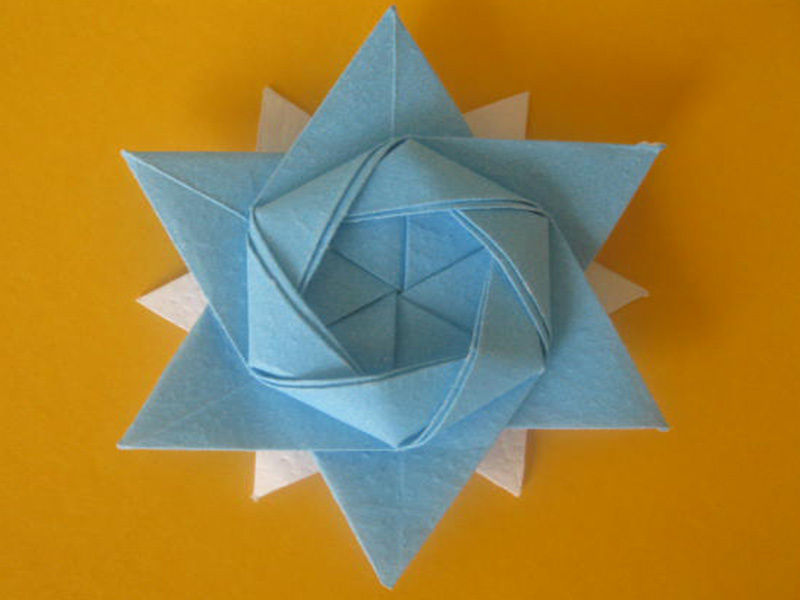

One way that Ashkenazi Jews beautified their homes for Shavuot was by creating and displaying paper cuttings. Called in Yiddish, shevuoslakh (or shavuosl) and royzalakh (or raizelach) – literally meaning little Shavuots and little roses – the paper cuttings were mounted on windows, so they would be visible both indoors and out. In her poem, Snowflakes, my mother called them, Piercy recollects, “Grandma tacked hers/ to the walls or on window/ that looked on the street/ the east window where the sun/ rose hidden behind the tenements” – with the rising sun evoking the rose of the Shavuot raizelach.

Paper cutting was not unique to Shavuot. It developed as a folk art form centuries ago, in both Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities. As art forms go, paper cut art is democratic: at its very basic, it requires relatively inexpensive raw materials – paper and some sort of cutting tool, and perhaps something to add colour. Old newspapers, wrapping paper and used writing paper may be redeployed for this purpose. Even people with little artistic talent could produce pleasing designs, and gifted artisans could dazzle.

But for Ashkenazi Jews, there was a particular link between paper cutting and Shavuot, which stems from an old practice of decorating homes and synagogues with flowers, branches, boughs and trees. In shtetl culture, cut flowers were a luxury – pricey and perishable. And Jewish culture was deeply literate, so paper – especially used paper – was always around and available for artistic repurposing. Some sources cite the objection of 18th century scholar Vilna Gaon to the Shavuot greening as another reason for the development of a Shavuot paper-cutting tradition. Because church decor involved cut flowers and pagan practices involved trees, the Vilna Gaon viewed such customs as inherently non-Jewish. Although most communities and religious authorities did not follow the Vilna Gaon’s ruling, paper-cut flora offered a good resolution of religious and economic restraints.

Most striking, however, is the disappearance of this Shavuot folk custom with the 20th-century movement of Jewish populations to North American – so much so that both Piercy and I had only fuzzy memories of the practice.

In addition to their deep textual roots, Jewish holidays reach back into family memory, into inherited and lost traditions. Our impulse to beautify, to craft art and graft it onto what’s most important, connects us with legacies we may have forgotten. Piercy reflects, “I had lost it all/ until a woman sent me a papercut … and then/ in my hand I felt a piece of the past/ materialize, a snowflake long melted,/ evaporated, cohering … once/ again … made of skill and absence.”