In honour of Canada’s 150th birthday, The CJN presents 40 profiles of some of the most prominent Jewish Canadians throughout our history.

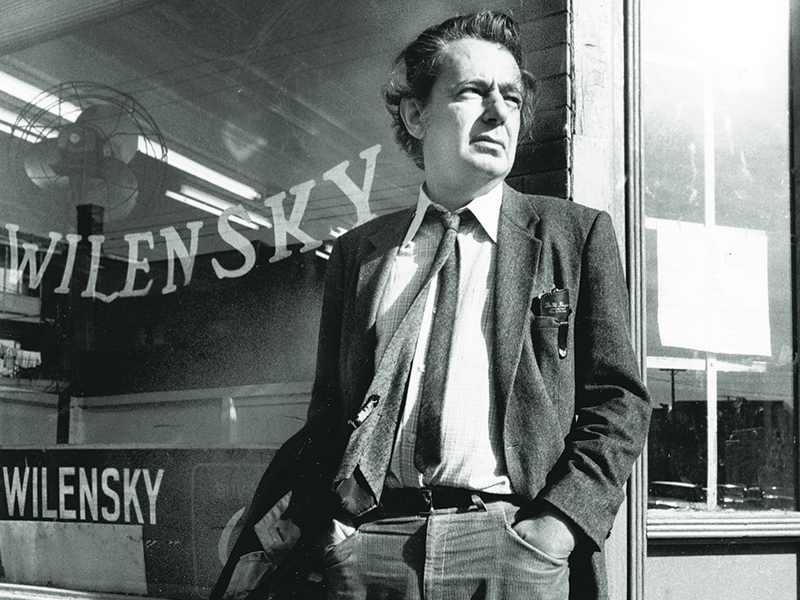

Novelist Mordecai Richler, creator of such memorable fictional characters as Duddy Kravitz and Solomon Gursky, immortalized the working-class Montreal Jewish milieu, in which he was born.

In his latter years, he turned increasingly to journalism, penning polemical essays excoriating Quebec nationalism, which earned him the opprobrium of many francophones and clouded his literary legacy in his home province.

Born in Montreal in 1931, Richler died in July 2001.

The son of Lily (née Rosenberg), whose father was an Chassidic rabbi, and Moses Richler, a scrap dealer, the author grew up on St. Urbain Street in the district now known as the Plateau and attended Baron Byng High School, locales that colour much of his work.

From early on, Richler exhibited a rebellious, iconoclastic nature, alienating him from his birth family and later ruffling the feathers of the Jewish community with his biting satire. He also chafed against the rigidness of the (anglophone) Canadian establishment of the time.

READ: THE CJN’S SPECIAL COVERAGE OF CANADA’S SESQUICENTENNIAL

Even before he waded into politics, Richler never hesitated to express his opinions bluntly, no matter whom he offended. He called it being “an honest witness to his time and place.”

An indifferent student, Richler dropped out of Sir George Williams College (later Concordia University) at 19 and headed to Europe, where he spent time in Paris and Spain. In 1954, he settled in London, where he would live for two decades and produce the majority of his 10 novels, the earliest of which were The Acrobats and Son of a Smaller Hero, both dark, serious works, quite unlike those he produced later on.

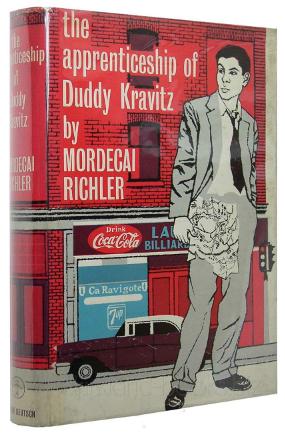

His fourth novel, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1959), established Richler as a Canadian writer of the first order, even as the book aroused mixed feelings. The story of a young Jewish man from a poor family in Montreal who was determined to make it no matter what it took, became a staple of Canadian literature. It has been adapted to film (Richler received an Oscar nomination for the screenplay of the 1974 movie starring Richard Dreyfuss) and the stage.

His other major novels include St. Urbain’s Horseman (1971), the sprawling saga Solomon Gursky Was Here (1989), which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and the uncharacteristically sensitive Barney’s Version (1997), his last novel.

His 1992 non-fiction work Oh Canada! Oh Quebec! followed on an article in The New Yorker, which mocked the Parti Québécois’s (PQ) separatist goals and language laws, while dissecting historical anti-Semitism among French-Canadians. It caused an uproar in the province and deep discomfort in the organized Jewish community. Richler cared little; he dismissed its leaders as “court Jews.”

Journalist Jean-François Lisée, the PQ leader today, said back then: “The contempt that he has for Quebecers, and for the facts … hurt me as a Quebecer.… It gave me an enormous headache to read this book, it stopped me from sleeping.”

Unbowed, Richler twisted the knife with the creation of the Impure Wool Society and the Prix Parizeau awards, to be bestowed annually on a non-pure laine Quebec writer. It ran for a couple of years, by which time Richler had made his point.

Exhibiting a softer side, the prolific Richler also wrote a children’s series, entitled Jacob Two-Two, named for the youngest of his five kids.

In 1994, he published the travel book, This Year in Jerusalem, a memoir of an extended stay in Israel. Richler reconnected with former members of Habonim, the secular Zionist youth group of which he was a part of in the 1940s, who made aliyah. He examines his own youthful idealism about the creation of the Jewish state, the complexities of modern Israel and what it means to live in the Diaspora.

On the 10th anniversary of his death in 2010, Montreal councillor Marvin Rotrand launched a campaign, with the support of Richler’s family, to have the city create a permanent memorial to the writer, such as renaming a street or park after him. The response largely ranged from tepid to hostile, an indication of the ambivalence, if not antipathy, toward Richler that lingered. The ultra-nationalist Société St. Jean Baptiste termed him “anti-Québécois.”

After much dithering and a change of administration, the city named the Mile End public library after Richler in 2015.

His abrasiveness aside, Richler’s literary talent was recognized with numerous honours, including two Governor General’s Awards, two Commonwealth Writers Prizes, the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour and the Giller Prize. In 2001, shortly before his death, he was appointed a companion of the Order of Canada.

Charles Foran, author of the award-winning 2010 biography Mordecai: The Life and Times, wrote that his subject was “from the start a complex and uncompromising figure, at once rejecting many of the formal tenets of his faith, while embracing its intellectual and ethical rigour.” The result was “an innately absurdist vision of life.”

There seems to be some softening in the attitude – or at least renewed interest – among francophones in the last couple of years.

‘He had an an innately absurdist vision of life.’

In 2015, Les Editions du Boréal became the first Quebec publisher in some 40 years to put out a new translation of a Richler work: Solomon Gursky. It has since been followed by Le Cavalier de Saint-Urbain, L’Apprentissage de Duddy Kravitz and Joshua.

Although Richler’s novels have been translated and published in France over the years, Boréal believes these local translations are truer to Québécois French, which is appropriate, given where the stories take place.

The publisher places Richler “among the greatest names in Canadian literature, and he is certainly, with Leonard Cohen, the anglo-Montreal writer who enjoys the greatest international renown.” It hopes the books will attract a younger generation of francophone readers.