TORONTO — After five years of research, reading hundreds of documents and writing 440 pages, Joseph B. Glass last month became the first Canadian to receive an award from the Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre last month.

TORONTO — After five years of research, reading hundreds of documents and writing 440 pages, Joseph B. Glass last month became the first Canadian to receive an award from the Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre last month.

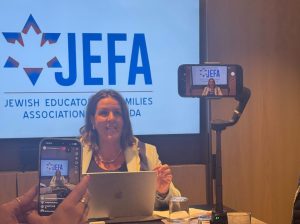

Joseph B. Glass [Rita Poliakov photo]

Glass, along with co-author Ruth Kark, received about $10,000 (US) this past December for their book Sephardi Entrepreneurs in Jerusalem: The Valero Family 1800-1945, which explored the development of banking in Ottoman Palestine by telling the story of the Valero family, who, in 1848, developed the first private bank in what is now Israel.

The competition, which recognizes academic research on Turkish banking and economic history, was run by the Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre, the European Association for Banking and Financial History and the History Foundation of Turkey. The award ceremony was held in Turkey.

For Glass, who teaches Canadian studies and geography and tourism at Centennial College in Toronto, and Kark, a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel, the award came as a surprise, mainly because of the timing of their submission.

“If we take the timing of how Turkey and Israel relations deteriorated a little bit [in 2008, when the entry was submitted], we thought, ‘Well, maybe just because the book talks about Israel, they’ll overlook it,’” Glass said. “I hope [the award] is an expression of their academic freedom.”

The book itself, which took Glass and Kark about five years to write, looks at the history of Sephardi Jews in Jerusalem, a side of Israel’s history that many researchers ignore, Glass said.

“There are things that, in history, they sort of get lost,” he said, adding that this is often the case for the Sephardi families he’s studied and written about.

“This whole group of Sephardi families were a fascinating study that had been overlooked. Usually, when it comes to history… whoever writes it, write what they want,” he said.

According to Glass, the research was hindered by Israel’s Labor government several decades ago, which “followed certain ideological directions when it came to Sephardi Jews.”

Kark, who met Glass when he was her PhD student at Hebrew University, agrees that more research needs to be done on the subject.

“It’s a topic that is neglected, especially by Jewish researchers and scholars. It is important, it has an international [importance],” she said.

When entering the competition, the authors hoped the fact that their research was unusual would be recognized.

“There was the hope that they’d pick up on the uniqueness of telling the story of a bank,” Glass said. “[The judges said] they found the intermingling of social and financial history to be fascinating.”

Glass and Kark originally started work on the book after being approached by the Valero family. They were given access to bank statements, personal diaries and letters that had never been published. The authors found out that the Valero family dealt with the finances of visiting royalty and that they had their own synagogue, which still exists in Jerusalem.

This book is one of several projects that she and Glass have worked on together, Kark said, adding that 20 years ago, Glass was her teaching assistant at Hebrew University.

“He learned a lot about the local things [in Israel], the local history. He was a wonderful student,” she said.

“Joseph also had a wonderful character, which probably comes from Canada. He’s very considerate and a very nice person, apart from being a talented scholar.”

Glass, who is currently working on a new book about Canada and the Holy Land, will use his part of the award money for his research, while Kark is considering adding it to a fund she keeps for her master’s and PhD students who need financial support.