On a Sunday morning, the Jewish community centre in the northern suburbs of Toronto bustles with activity.

It’s a few weeks before Passover, and the classrooms are filled with children crafting Moses in the basket out of tissue paper and practicing singing the Four Questions.

Parents sit poolside watching their children’s swim lessons, while nearby, a trio of preteens devours french fries from the kosher café.

Next door, at the Jewish high school, hundreds more children are equally busy in Sunday schools run by local Reform and Conservative synagogues.

A casual observer looking at the spacious, modern buildings filled with hundreds of families would think Toronto is in the midst of a Jewish renaissance. The truth is more complex.

Come Monday, those same, expensive buildings will be half-filled, as some Jewish day school branches in York Region struggle to attract a critical mass of students.

Last month, the board of the Anne and Max Tanenbaum Community Hebrew Academy of Toronto announced that due to sharply declining enrolment, the northern campus was closing and the school was merging with the southern branch in Bathurst Manor. At the same time, UJA Federation of Greater Toronto announced that $15 million in donations had been earmarked so the school could slash tuition by one-third.

READ: STUDENTS AND PARENTS RALLY TO ‘SAVE OUR SCHOOL’

Meanwhile, the Leo Baeck Day School, a Reform movement school, has sold its building in York Region and is moving into what will be TanenbaumCHAT’s former northern campus next fall.

But travel a few kilometres south of the bustling campus and the picture is starkly different. It’s hard to see any signs of life on the expansive grounds where a Jewish community centre and theatre once stood. The Jewish community centre (JCC) on Bathurst Street just north of Sheppard Avenue was torn down in 2009, and plans to rebuild it have been repeatedly delayed by a lack of funds. Two buildings – one used for Jewish communal offices, the other housing a daycare and fitness studio – sit on the grounds. (Even further south, there is another busy downtown JCC, but it’s not on the radar for midtown families looking for a swim class, basketball league or even Jewish programming.)

Steeles Avenue, the dividing line between the City of Toronto and its northern suburbs, is also another informal border: south of it, day schools are stable, even growing, although many residents bemoan the lack of a fully equipped JCC. North of Steeles, there is a rapidly expanding young population and new buildings, but struggling schools.

◊

Adam Minsky, president and CEO of UJA Federation of Greater Toronto, who has been in the job for less than a year, says there is no connection between the challenges facing the Jewish day school system and the state of the community’s infrastructure.

READ: SURVEY OF YORK REGION JEWS AIMS TO BOOST ENGAGEMENT

“I agree that we’ve gone too long without a proper [midtown] JCC,” he says. “JCCs are vital community institutions, There should be one on this [midtown] campus, as there is one downtown and one in York Region, just as I believe Jewish education is something that should be afforded to Jews whether they live in York Region, downtown or midtown.”

Construction will start on a JCC in midtown Toronto this fall, if Minsky can raise $5.25 million, a goal he says is realistic.

Day schools’ competition

The education puzzle is more complicated. South of Steeles, Toronto public schools are perceived as being uneven in quality. Here, the biggest competition for day schools are independent private schools, and, to a much lesser extent, public schools, Minsky says.

But north of Steeles, day schools are competing with public schools that boast student populations that may be predominantly Jewish and offer high-quality education in newer buildings, he says.

Jewish day schools, especially TanenbaumCHAT, with its tuition of $27,000 this year, can’t compete. In the fall of 2017, TanenbaumCHAT projected that just 48 students from all Jewish day schools would have entered its Grade 9 program at the northern campus, compared with 119 at the southern branch.

Jewish education narratives in York Region

York Region, especially its northern edges, is home to the youngest Jewish population in the Greater Toronto Area, as well as a significant number of immigrants, according to an analysis of the 2011 census done for federation. About half of the Jewish immigrants from Israel – 9,030 people – and the former Soviet Union – 20,060 people – live in York Region.

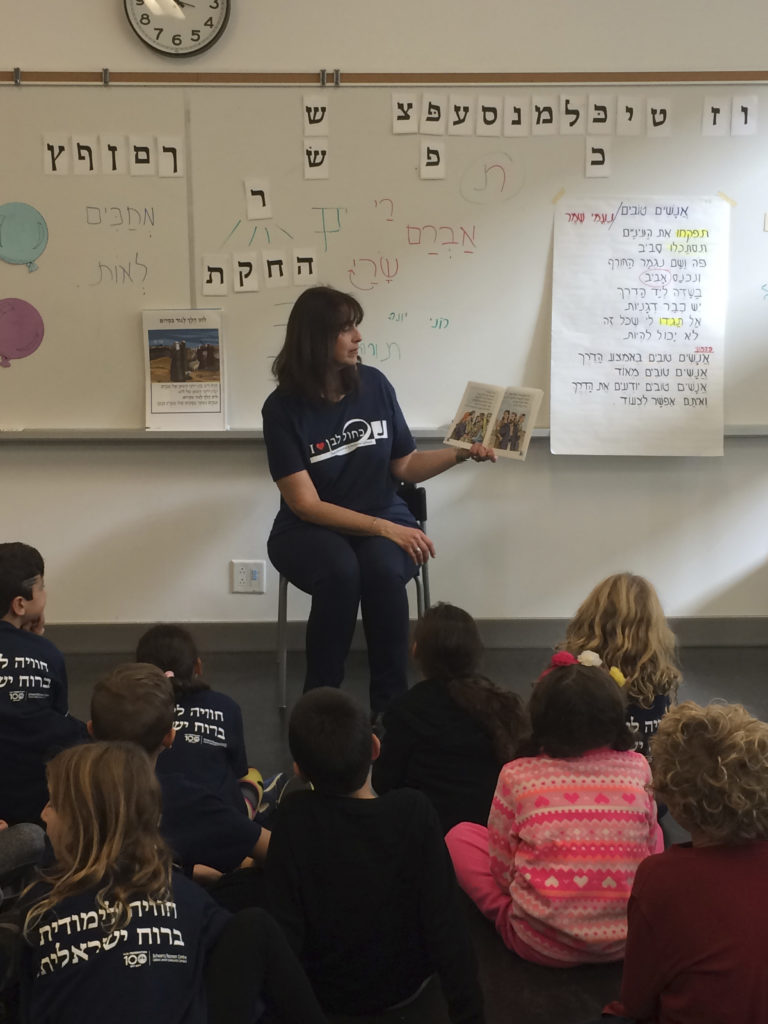

These are the families who support Kachol Lavan, a Sunday school for Israeli children, and J. Roots, a school that was started for children of Russian speakers, but has since broadened its reach. Both schools were launched less than 10 years ago by concerned mothers in their basements, which they quickly outgrew. Today, J. Roots has 400 students and Kachol Lavan has 240 children enrolled.

READ: LETTER FROM SCHOOL LEADERS: BUT COMMUNITY WILL BENEFIT FROM CHAT MERGER

The schools teach about the holidays, the Bible and Israel, but through a secular lens.

Eti Zeharia, a teacher at Kachol Lavan and parent of two girls, 8 and 10, who attend the school, said she was “devastated” when she realized that as a newcomer from Israel, she could not afford to send her children to Jewish school here.

“We really wanted to have Jewish education for our family,” she says. “I was really stressed over it. Thank God someone told me about Kachol Lavan.”

Her daughters enrolled in French immersion public school and speak Hebrew and celebrate Jewish holidays at home. If she were starting over, Zeharia says she would only look at the Sunday school for her daughters’ Jewish education.

These programs leave a bitter taste for at least one day school administrator, who argues that UJA Federation has invested in these programs without evidence that they actually foster a strong Jewish identity.

“There is a new narrative, that if you are Israeli or you are Russian, the community has created a half-day alternative program for you,” says the day school head, who did not wish to be named because of the sensitive nature of the topic.

“In the old narrative, the day schools would help acculturate families.”

The educator lays the blame on federation, charging it has abdicated its role of getting new immigrants’ children into the day school system.

Minsky denies this, pointing out that federation allocates $10 million for tuition subsidies annually.

“We are doing the same now as we did then for newcomer families,” he says.

It’s middle-income families who are having a harder time affording day schools, he says.

More than money

But it’s not only money that has kept Jewish children out of the region’s day schools.

Six years ago, Rabbi Erin Polansky started a Reform congregation called Neshamah in the northern half of the region. Neither Rabbi Polansky nor the majority of her congregants send their kids to day school. Many choose public French immersion schools, which are bursting at the seams in the region.

This year, for the first time, TanenbaumCHAT made a presentation to her school’s grade 7 and 8 students, but Rabbi Polansky says her congregants are not the school’s market.

“I don’t think it’s about the money. Our parents have chosen public schools because that reflects their values. We value public education, and diversity. It’s a values argument, not a money argument, ” she said.

“Public school is not a second-best default because I couldn’t afford private school.”

Jewish identity can be nurtured as effectively in the home and at Jewish summer camp as in day school, she says.

Neshamah, which holds some services at the North Thornhill Community Centre and Sunday school at TanenbaumCHAT’s northern branch, was designed to appeal to the region’s young families, who don’t want the expense of a shul with its own building and accompanying high dues.

“This is a neighbourhood where both parents are working, [and] there’s a lot of single parents working,” says Rabbi Polansky. “For this generation, building synagogues and paying for institutions is not in the works.”

Neshamah, which has a membership of 150 families, meets monthly in the community centre and members’ homes.

“My generation isn’t filling their Jewish needs with prayer,” says Rabbi Polansky, 42. “It’s more about events, celebrations and informal gatherings.”

The congregation hosts Friday night potluck dinners, Havdalah services that lead to an evening of bowling, and picnics in the park. But despite its family-friendly, cost-conscious approach, Neshamah has not attracted many immigrants.

“For a lot of first-generation Canadians, it’s not in their culture to pay for membership in a Jewish community or Jewish education,” she says. “We have a handful of Israeli families. They’ve been here for a long time, long enough to realize that their kids are Canadian and need to be part of a Jewish community in some formal way.”

Meanwhile, as housing prices continue to soar in the Toronto area, young Jewish families are moving even further north. At J. Roots supplementary school, students are now coming from Barrie, Bradford and Newmarket, says director Tova Hovich.

At a town hall meeting last month to discuss the imminent closure of TanenbaumCHAT’s Vaughan branch, families vented their anger at the federation, accusing it of turning its back on York Region and these burgeoning communities.

A wakeup call?

For his part, Minsky says federation is not going to get involved in making decisions about the operation of day schools, but it remains committed to funding summer camps, schools and community centres in York Region.

The closing, however, highlights that the way planning has gone on in York Region needs to change, Minsky said.

“York Region has been through an exciting period of growth where many different organizations have pursued their independent plan of how they want to grow,” he said.

“Some of the changes that are happening now have served as a wakeup call that we need to work together, federation and these organizations, to plan on a community-wide basis, so we don’t end up in situations with changes that need to be made that are negative for the community.”