Online hate can predict antisemitic incidents in the real world, delegates to a two-day conference on antisemitism heard. The conference, organized by the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, was held in Ottawa Oct. 16-17.

Hamas’ Oct. 7 attacks on Israelis and the ensuing war, have made the focus on the online world even more important, said Joel Finkelstein, chief science officer and co-founder of the Network Contagion Research Institute at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Citing a study done by the institute of online hate in Canada in 2021 following conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, Finkelstein said the rise in online hate was “a predictor about real-world actions.”

“What we see on social media turns up in real life,” he said. The analysis by his institute of more than 100 million social media posts during the conflict in 2021 showed a relationship between online antisemitic remarks and actions against Jews a week or two later in Toronto and Montreal.

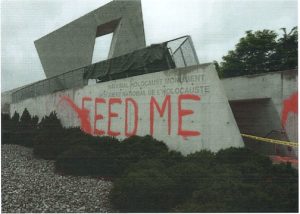

This included antisemitic activities such as chants of violent slogans against Jews during protests, vandalism of synagogues, hate graffiti in Jewish neighbourhoods, and other hate crimes.

Noting there has been a rise in hate speech directed at Israel and Jews since the Oct. 7 attack, Finkelstein said this was a “signal of what’s to come.”

There is, he added, a “looming anticipation of a similar surge in antisemitism in Canada. We have already started to see several similar trends emerging.”

How does it spread so fast? While content on social media is usually created and shared by ideological hate groups, it is then propelled by ‘bot farms’ and troll accounts operated by authoritarian regimes like China, North Korea and some in the Middle East, that “want to disrupt and destabilize western democracies,” Finkelstein said.

This is evident when social media accounts with fewer than a hundred followers suddenly get thousands of likes and shares, he said.

Through his institute, Finkelstein also tracks hate towards other minorities in the United States such as Muslims and Hindus, then reports the findings to law enforcement agencies, the FBI, politicians and others.

This includes reporting to social media companies to let them know what’s happening on their platforms. “We alert them so they can respond in good faith,” he said.

Finkelstein believes Jews in Canada could lead the way in helping to set up an early warning system in this country.

Such a system should not just be for Jews but for all minorities, since “community security must evolve in the age of information disorder to meet these threats with faster, real-time data collection,” he said.

Becca Wertman-Traub directs research for the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA). She agreed with Finkelstein that such an early warning system would be helpful in Canada.

“In 2021, we didn’t make the connection between social media and actions,” she said. “Now we are aware of the relationship between the two. It shows we can anticipate something after a spike in online hate towards Jews.”

Comparing such a system to one that warns people about impending hurricanes, watching for hate on social media can be a warning for Jews or others to get ready.

Currently, all CIJA can do is react since information about hate from Statistics Canada is a year old, based on reports from police across the country.

That, she explained, is like doing clean-up and recovery work after a storm instead of proactively getting communities, governments and police ready so they can be prepared and weather it better.

Plus, she added, police do not have a uniform way of reporting hate, so it is hard to see trends.

That’s why research is so important. “By tracking social media, we can get current data by the day, hour and minute,” she said. “We can act much quicker.”

Such a system doesn’t currently exist in Canada, but CIJA is exploring it as an option, she noted.