Everyone in Montreal seems to know Sheila Kussner and Hope & Cope, the charity for cancer patients that she founded. Her extraordinary accomplishments and the news of her death at age 91 on Aug. 6 elicited a shockwave and outpouring of love across Canada.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Kussner was “a dear friend” to him and his late father, Pierre Trudeau.

“Sheila Kussner was a remarkable Canadian and a steadfast advocate for people living with cancer and their families. Sheila had a profound impact on her community of Montreal and changed countless lives through her organization Hope & Cope.

“She truly embodied the values of tikun olam, and because of her leadership and dedication, Hope & Cope continues its transformative work improving the lives of those impacted by cancer and championing a compassionate and peer-based support approach to care.”

Kussner founded Hope & Cope in 1981 and it became a blueprint for cancer support around the world at a time when a diagnosis of the disease was still considered a death sentence.

Prior to her death she set her sights and succeeded in securing $20 million for an endowment to ensure the future of the organization.

Although the impetus to start Hope & Cope was her husband Marvyn’s battle with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in the 1970s, Kussner had already endured a shocking experience of her own. At age 14 she was diagnosed with a rare form of bone cancer and faced the amputation of her leg.

Kussner had a 5 percent chance of survival without the amputation and the odds hovered around 11 percent with the surgery. Initially she wanted to take the risk, avoid an amputation, and live her life as a young, beautiful teenager. A family friend who was also a doctor convinced her otherwise, telling her bluntly that it was a selfish decision and without the amputation she would die leaving her brothers and parents devastated.

Rabbi Adam Scheier of Montreal’s Congregation Shaar Hashomayim explained in his eulogy, “She knew life is a gift. By all statistics, she wasn’t supposed to live this long. She realized that she was here on borrowed time, and she was here for a reason. Being an amputee was not how she defined herself. It was not the focus of her life, it was just another challenge to overcome on the way to fulfill a meaningful existence.”

Kussner eschewed the accolades—it’s estimated that she raised more than $100 million for Hope & Cope—but told her friend Suzanne O’Brien, president of the organization’s board of directors exactly how she wanted to be remembered.

“She would say, ‘Hope & Cope is not about me. The more important principles of its success and future start and end with its staff, volunteers, healthcare colleagues, and donors.’ No one ranked higher in her estimation than those willing to give of themselves to others. Whether it be time or money or both.

“She was essentially a private person who would rather talk about others than herself.” O’Brien eulogized. “Sheila was a great believer that no one person can change the world but each of us has the capacity to change the world for one person, even if just for a short time.”

Her “sparkle and zest for living” which granddaughter Carolyn described, cemented her reputation as Montreal’s premier fundraiser. While her Rolodex included the ‘who’s who’ of Montreal who were wined and dined with a mission, the Kussners lived modestly in the same Mont-Royal bungalow that they purchased early in their 60-year marriage.

Daughter Janice described her father Marvyn to The CJN as “The wind beneath her wings.” Daughter Joanne added, “Her marriage was a fairytale filled with deep love and support. My mom didn’t achieve all that she did without a husband like my dad.”

He supported Sheila’s fundraising and founded PROCURE, a non-profit organization to provide men with information on prostate cancer after he was diagnosed in the early 2000s. He died in 2013.

Sheila Kussner was born in Montreal to Jack and Sophie Golden and was a younger sister to brothers Clifford and Ronnie. Her father’s family emigrated to Canada from eastern Europe in the early 1900s. Her father spent his childhood in Prince Edward Island before the family moved to Montreal where he became a successful insurance salesman. Her mother left Russia in 1908 with her family and settled in Montreal. Sheila attended McGill and met her future husband Marvyn at Camp Hiawatha in Sainte-Agathe.

Kussner’s energy extended well beyond Hope & Cope. She advocated for the ‘no’ vote in the 1995 Quebec referendum, worked tirelessly to help draw attention to the plight of refuseniks in the 1980s and raised $30 million to establish the Department of Oncology at the Faculty of Medicine at McGill University.

She also helped secure funding for the Jewish General Hospital’s Palliative Care Unit and other oncology-based programs. If she met someone whose philanthropic interests didn’t align with Hope & Cope, she would enthusiastically point them to another charity.

Her daughter Janice described her mother’s propensity for kindness at the funeral. “Mum was generous with gifts, gift certificates, and beautiful flowers to make others happy and her thank you and condolence notes which she would write till the wee hours of the morning.

“She taught us to approach every day with a heart full of understanding and a commitment to making the world a gentler place, just as she did.”

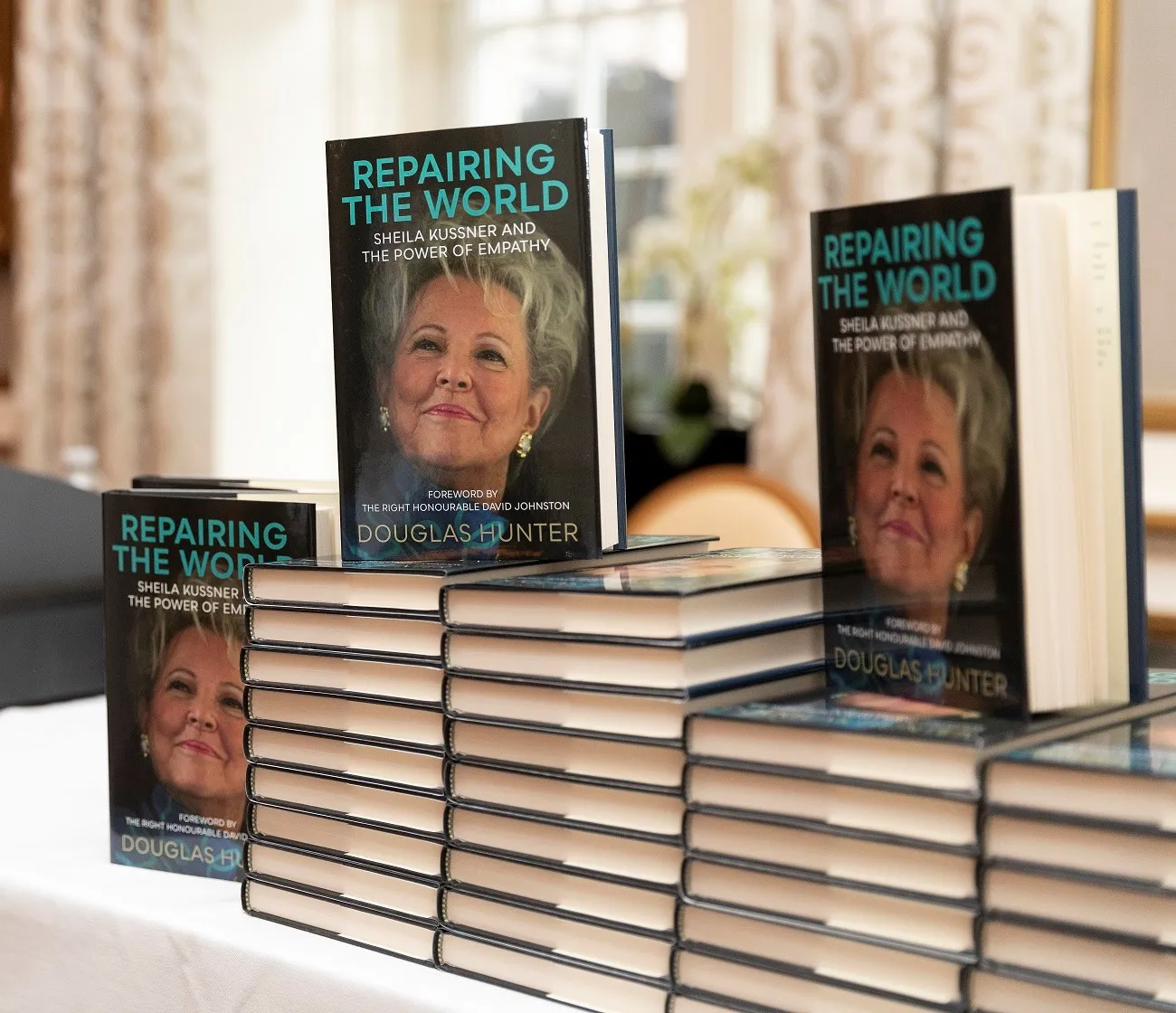

Douglas Hunter, the author of Repairing the World: Sheila Kussner and the Power of Empathy, her biography, was the recipient of many of these calls and notes. “We started writing the book in the summer of 2021. It was COVID. I came to Montreal several times and met Sheila in her kitchen. She really was a friend by the end of it,” he told The CJN.

“She called me early this month to let me know she finally had read the book and she loved it and was sending me a note. She wanted to check my address. I found out the following Tuesday that she died. The note showed up the next day with a gift card tucked in it.”

Hunter said that until the end, she was still seeing her ‘patients.’ “These were people she took care of unofficially and privately. She would make sure they had meals, she would arrange medical appointments for them—many were people she’d never heard of before.

“She would find out that someone was waiting for test results or an appointment with a specialist and she knew how to pull strings and would make calls. During COVID, if she found out someone was alone at home she would send meals to them. She was constantly looking out for people.

“She was still doing it to her last days.”

Sheila Kussner is survived by her daughters Janice and Joanne and grandchildren Carolyn and Justin. She was an Officer of the Order of Canada, Officer of the Order of Quebec and Commander of the Order of Montreal.