From licensed security agencies to uniformed volunteers and marked patrol cars, multiple groups are actively offering services designed to keep watch over Jewish areas and activities in Toronto.

But concerns about the nature of their operations have increased over time, especially now that UJA Federation of Greater Toronto spun off the Jewish Security Network (JSN), which operates as an independent agency.

Demand for increased protection has grown during a year of increased attacks and protests that have repeatedly targeted synagogues, businesses and events.

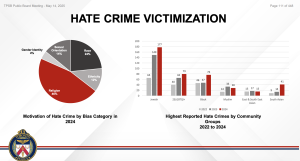

Plus, according to Toronto Police Service (TPS) statistics, suspected or confirmed hate crimes have disproportionately targeted Jewish communities. Since last Oct. 7, about 45 percent of hate-crime occurrences in police reports are antisemitic.

Antisemitism has remained the single highest-bias category, with the most common charges consistently being mischief (including graffiti), assault, and uttering threats.

Toronto Police spokesperson Stephanie Sayers told The CJN via email that it’s the prerogative of individual communities to take up, organize, and invest in their own unique security needs.

“TPS supports any community’s efforts to enhance its own safety and security, as long as those efforts comply with legal requirements and work in partnership with law enforcement,” wrote Sayers. “The safety and well-being of all Torontonians is a priority, and we recognize the role that private security agencies can play in contributing to this goal.”

Reactions to these security groups remain, predictably, mixed and prompt questions about what they are legally allowed to do to protect Jewish communities or others.

But critics have also branded them as vigilante organizations.

Police are collaborating with representatives of the UJA-backed JSN on community security efforts, Sayers confirmed via email, “as we do and have always done with various community-based security initiatives and similar organizations… ensuring that any private security measures complement public safety efforts, while maintaining open lines of communication.”

JSN director Jevon Greenblatt spoke about community-wide levels of alertness when he was introduced during a UJA webinar in September.

“The real security is done in vigilance, in awareness, in making sure that we are aware of what’s happening: We’re addressing suspicious activity around [Jewish gathering spaces]… We’re reporting that kind of stuff.”

JSN will take the lead on awareness training sessions for synagogues, schools and Jewish institutions, consult with Jewish institutions to improve security infrastructure at their buildings, including support for synagogues applying for federal grants.

But in addition to JSN, several smaller groups—unaffiliated with UJA Federation—have taken shape over the last few years in Toronto.

The CJN’s reporting below outlines the background of three of these organizations, concerns related to the legacy of the Jewish Defense League (JDL), and concern—along with questions raised—over their recent presence on local university campuses.

Shomrim Toronto

Shomrim Toronto is a volunteer group that has become more visible at large events like the UJA rally at Congregation Beth Tzedec in November 2023, and the Oct. 7 anniversary memorial event at the Sherman Campus of the Prosserman JCC. They have also been observed managing traffic at protests that occurred outside synagogues where pro-Palestine and pro-Israel groups clashed.

A spokesperson for Shomrim Toronto—who asked not to be named to protect their family’s identity—said the organization (founded in 2021) responds to calls from the community, and reports all potential safety concerns to police.

Shomrim team members are entirely volunteers. Their duties might include referring critical calls or incidents to authorities including police, looking for lost children, or accompanying Torah celebration processions along residential streets.

Magen Herut Canada

In recent months, security and surveillance teams established by Magen Herut Canada have separately begun to appear at public events, notably including a protest Sept. 6 that began at the University of Toronto campus where an encampment stood throughout the months of May and June.

Magen Herut Canada’s “surveillance team” leader, Aaron Hadida, has posted photos of himself with a body-worn video camera on his flak vest, similar to the one worn by police.

Hadida says in the weeks after the Hamas attacks on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, several neighbourhood-based WhatsApp groups formed to bring “extra eyes and ears” to Jewish areas of the city. He later formalized the operation, he says, through invitations to specific, capable people to join the safety patrols.

With the title of national director of security for Herut Canada, he disputes the “vigilante” characterization and says the group consists of nearly all licensed security guards. A registered charity, donations to Herut Canada via a Chesed Fund web page for the Magen Herut team go toward protective gear and security license fees for a few existing volunteers, says Hadida.

The group organizes free Krav Maga workshops in the community, and team members are required to train on Sundays at their teacher’s dojo.

Herut shows up when requested to secure events, Hadida says—although on Sept. 6, he says he attended to ensure the safety of Jewish students “after the year they’ve had.”

The fenced-in protest encampment at the University of Toronto downtown campus in May and June, led by protest group Occupy UofT for Palestine, saw both Jewish counter-protests at, and Jewish support for, the occupation of the grassy quad before an injunction from an Ontario Superior Court judge ordered it dismantled.

The encampment ultimately generated safety and hate speech concerns from a number of Jewish students and faculty at UofT, many of whom avoided that part of campus during the two-month protest occupation.

Hadida says he makes a point of coordinating with police or campus security (and deferring to, or assisting them, he says). “If there’s police, I walk up to the officer, let them know why we’re there,” says Hadida.

“Everything we do is above the board and lawful.” Hadida says he’s never caused a problem “on any campus,” and that he vets recruits carefully to keep out troublemakers.

“I’m a de-escalator. I’m a person that stops things, not initiates them.”

JForce Security

At the UofT protest scene, Magen Herut Canada partnered with JForce, a licensed security agency, which was registered as a Canadian business in March 2024. JForce’s security team posted photos of its members sporting JForce-branded tactical vests and walkie-talkies on the downtown campus.

JForce declined The CJN’s interview requests, saying the agency would take questions via email—but ultimately it did not respond.

Its presence at UofT on Sept. 6 was noted on its own Instagram account three days later, along with a screenshot of the positive attention its presence received from the Jerusalem Post, which cited a report from The CJN on what reporter Mitchell Consky observed that day.

On its website, JForce says the agency was “born of the need for a community aware, licensed, trained, insured and dependable team to turn to in times of need.” Its advertised services include safety assessments, event security, private investigations, and bodyguards.

The Sept. 6 demonstration, which began on the downtown St. George campus, became a procession for several blocks when demonstrators took over College Street, marching to the UofT Asset Management offices on Bay Street, where police kept demonstrators out, arrested one person, and used pepper spray.

After the crowd of protesters thinned out, two older women approached JForce members and asked them to walk the women to the nearest subway station, Consky reported.

“They said they felt unsafe and they just wanted an escort to get to where they’re going,” the member of JForce said, after four members escorted the two civilians. (JForce members have not typically offered their names when speaking to The CJN.)

Reactions at TMU

A back-to-school incident at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) reflects the mixed opinion on the role these community security groups play.

At TMU, after a Hillel tabling information event was disrupted by a loud protest, a community leader, who has been active in Jewish life on campuses, asked Hadida to send support for the next event. Magen Herut’s volunteer stood silently at a short distance from the table, which was not disrupted.

Hillel Ontario says it did not request the extra security for that event.

Malka Daniels, a law student at TMU and a past president of its Hillel chapter, says she relies on Hillel and the university to organize campus security, and feels more secure seeing the familiar faces of campus safety officers who recognize her, too.

“In my experience I don’t believe students have been seeking this additional security for things like tabling,” she says.

She encourages Jewish students to be strong in themselves “as opposed to [this] security presence, which draws more attention to the statements [protesters] are making.”

“[Students’] ability to be a proud Jew” shouldn’t require “external services to keep [us] safe,” she said.

However, Hadida says he usually only shows up where he’s been asked to provide security. The group was present in September when pro-Israel supporters silently protested at a Take Back the Night rally organized by the Toronto Rape Crisis Centre which ignored the rape, kidnapping and murder of Israeli women.

Hadida is often asked to consult on or provide security for a number of GTA synagogues, he says, an area he’s offered or volunteered for some years before the current Magen Herut initiative.

JDL’s yellow legacy

Critics taking issue with the presence of Hadida’s team and JForce on the UofT campus have attempted to link them to the presence of the Kahane Chai flag that was seen among counter-protesters at UofT on Sept. 6.

Kahane Chai (Kach) is listed by Public Safety Canada as a terrorist group, and its flag (in yellow and black) and the Jewish Defense League (JDL) logo both feature the Kahanist symbol.

A defunct far-right group that was focused on protecting Jews from antisemitism in their communities, it had been Kach’s paramilitary arm. JDL, which no longer exists by name in Canada, is considered inactive globally after 2015. Meir Weinstein, the former Canadian director who reportedly left the group in 2021 following a violent altercation in downtown Toronto—and is now promoting his advocacy efforts under the name Israel Now, and the Never Again Live podcast and social media account—still regularly counter-protests at pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Toronto.

Toronto Police would not comment on ongoing investigations around flags, nor on specific individual demonstrators, protest groups, or community security initiatives.

“We investigate every reported instance of hate, including at demonstrations, for hate crimes, or hate speech, or signage. This includes the presence of flags that promote terrorist organizations, as identified by Public Safety Canada,” Sayers wrote.

The charge of public incitement of hatred that can be linked to displaying terrorist flags or symbols requires a number of elements in addition to the symbol for charges to be laid, because, per the Criminal Code, the “hatred against any identifiable group” must also be one “where such incitement is likely to lead to a breach of the peace.”

Weinstein was personally banned from York University following his involvement, in 2019, in a chaotic protest where blows were exchanged over an event with an Israeli military reservist. (York University did not directly specify whether he is still prohibited in its emailed response to questions from The CJN.)

Hadida says he and his team have no links to that group, and refutes the conflation of his Magen Herut team’s presence with that of Weinstein and the Kahanist symbol on the flag.

Critics noted that a photo posted online shows Hadida in a JDL shirt—which he says is a picture from 13 years ago, and does not comprise a link to the group. Hadida says he met the group at counter-protests, but was never part of any organization.

“There was no such thing as members… they showed up to events or didn’t… there was never a form to sign… never a membership list. If you wanted to show up to a protest, they were the guys doing the counter-protests on Nakba Day or Al-Quds Day.

“Within the Jewish [community], if you [were] upset that something was happening… you were [at] an event, they were there handing out T-shirts, you took a free T-shirt… but I don’t walk around with a JDL T-shirt.”

Hadida has been with Herut Canada for a number of years before becoming its head of security. Though it was once a right-wing political party in Israel, Herut is now used as the name for an international network of advocacy organizations.

“We promote aliyah and support the right of Jewish communities to live and thrive throughout Israel, including in Judea and Samaria,” Herut Canada lists as one of its objectives on its website.

Aftermath at UofT

University of Toronto told The CJN that members of the public can generally access unrestricted areas of the campus, “as long as they abide by the law and university policies.”

The school also said no group has the right “to appropriate any part of our campus for their use to the exclusion of others,” and that “the university went to court to affirm this,” the university’s media spokesperson wrote.

“These principles are fundamental to our purpose as a centre of higher learning, discourse and scholarship.”

However: “Only police services and university Campus Safety officers have the authority to enforce the law on University of Toronto campuses.”

An academic perspective

Matthew Light, a professor of criminology at UofT, says one key issue with university campus spaces is that they are meant to be open to different views from a wider community, and have a mandate to promote dialogue and debate.

“There’s sensitivity of the university as a space where non-university security actors are involved in imposing themselves on the public, even if only in very limited ways… any kind of scenario where our particular institution is being contested in this way, I think is going to inevitably elicit more criticism and concern.”

Reports of surveillance, monitoring, harassment and intimidation around the encampment were well-documented in the UofT court injunction case, which led to an Ontario Superior Court justice ruling that the encampment violated university inclusion policies.

The court injunction decision noted that, while the specific, named defendants and encampment organizers were not proven to have expressed antisemitic views, Jewish community members who disagreed with the encampment certainly experienced harmful levels of antisemitism from it, whether or not it was distinguishable from anti-Israel speech.

The judge wrote that there had been “incidents of hate speech and physical harassment of people, predominantly but not exclusively directed at people wearing kippahs or some other indicator of Jewish identity in the general vicinity of the encampment.”

Post-encampment, that also becomes a precedent that’s hard to separate from the conversation, Light points out.

“Encampment organizers were keeping people out of the encampment, they were asking questions about people’s political views on the Israel Palestine dispute, and people were excluded… including by force,” said Light.

“I myself was told I was not welcome after I refused to answer the questions about the Palestinian movement that I was asked. Some Jewish professors, some Jews were told that they were not welcome. Some people who tried to enter without permission were assaulted…

“We need to recognize that, to some degree, the genie is out of the bottle, and that’s not the doing of the Jewish community, or any of these organizations.

“Our line as a community needs to be: ‘Security for Jews is not adequate right now.’ The university needs to better protect everyone equally, and to the extent that doesn’t happen, that doesn’t make it right for vigilantism to run rampant… but to some degree, the university itself opened the door.”

He’s careful to note the loaded term.

“If your political opponents are saying that they’re doing a safety patrol, you probably will find that offensive, and say that they’re [engaging in] vigilantism.

“Rather than throwing around the labels, I think we need to figure out the content of the intervention, who’s doing it, in what public institutional context, and make our judgments based on that.”

Light says that, at least in public spaces like campus—where neither a “surveillance team” t-shirt nor a keffiyeh worn as a face covering can be banned—such self-appointed security outfits might not serve the Jewish community’s best interests.

“If I were not Jewish, and I heard about [groups like Magen Herut and JForce attending the campus], I think I would say that the minimum I would expect [is] some kind of transparency from the university about why this is permitted… under what circumstances, and for whom is it allowed,” he said.

“The fundamental issue here is that the Jewish community probably does not want to get into an arms race with other members of the community of non-Jews about who is going to provide security on campus.”

Light explains that his concern relates to the presence of Jewish security groups in non-Jewish public spaces.

“I think the question should be framed in terms of the context in which the [security] intervention is happening. I think we can see that the involvement of Jewish groups in the security of [some] Jews is generating a lot of criticism and unease among non-Jews, not all of whom are hostile to us.”

Light says that unease ought to be “setting off some alarm bells” for Jewish Canadians, especially those uncertain about the community security groups.

“A good question to ask yourself as a citizen would be: How would I feel about some group that I strongly disapproved of doing the same thing?”

With files from Mitchell Consky, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Canadian Jewish News.

This article was republished on Oct. 20 to incorporate additional quotes and information sent to The CJN during a scheduled publishing break for the holiday of Sukkot—along with some minor clarifications and fixing a few typos.

Author

Jonathan Rothman is a reporter for The CJN based in Toronto, covering municipal politics, the arts, and police, security and court stories impacting the Jewish community locally and around Canada. He has worked in online newsrooms at the CBC and Yahoo Canada, and on creative digital teams at the CBC, and The Walrus, where he produced a seven-hour live webcast event. Jonathan has written for Spacing, NOW Toronto (the former weekly), Exclaim!, and The Globe and Mail, and has reported on arts & culture and produced audio stories for CBC Radio.

View all posts