Preservation of Yiddish songs and poetry of the Holocaust and pre-war Eastern European Jewry was the life’s work of David Botwinik, who died Feb. 9 at age 101.

The Vilna-born composer and music educator was a tireless advocate for Yiddish as a living language, and he used music to transmit its rich culture to younger generations.

His goal was not simply to document Yiddish music of the past but to revive it as an appreciated art form.

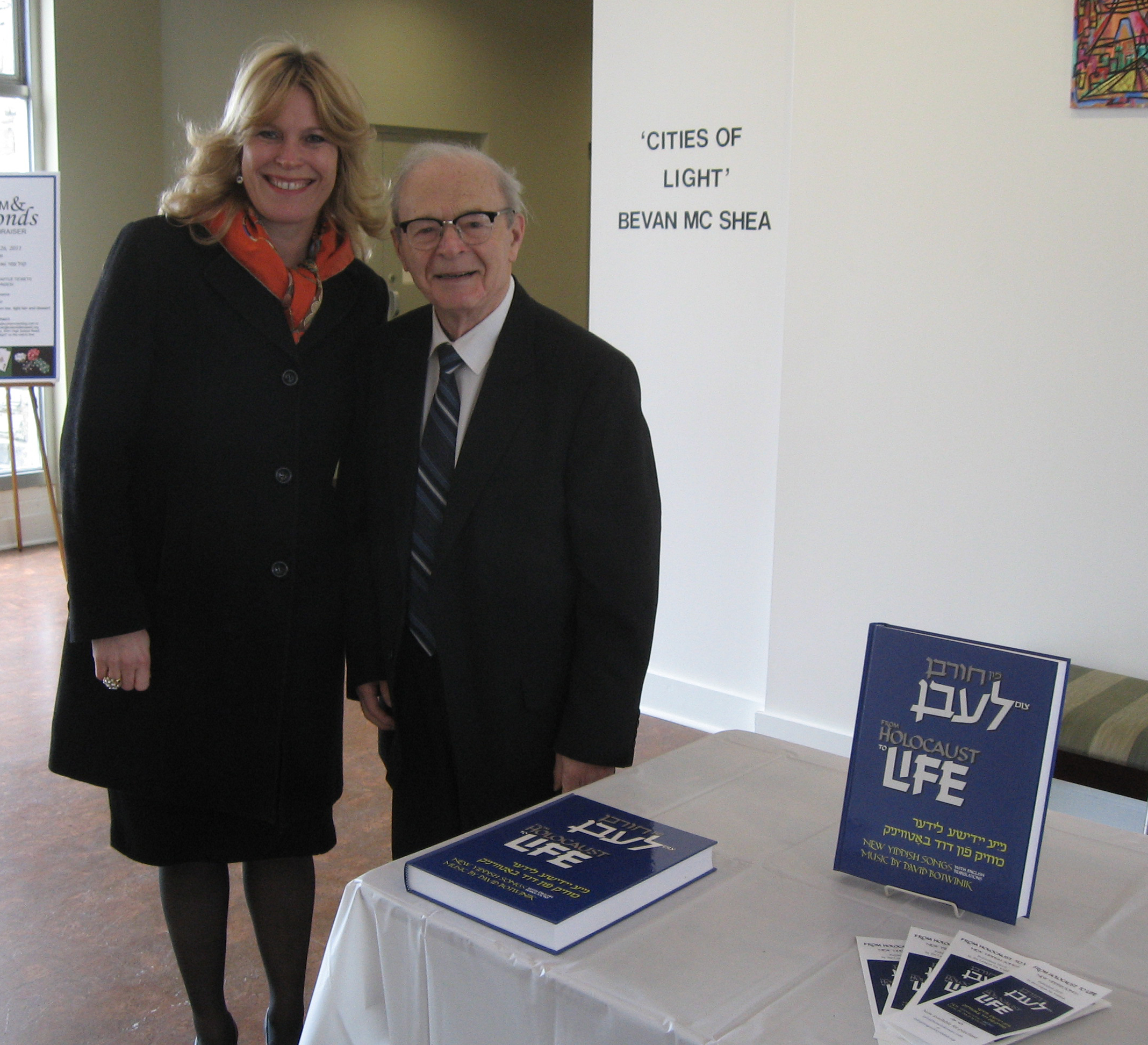

Botwinik’s magnum opus is From Holocaust to Life, a collection of his 56 original compositions based on the Yiddish poetry of such greats as Avraham Sutzkever and M.M. Shaffir, and 10 with his own lyrics, published in 2010 by the League for Yiddish in New York, with English translation.

Fifteen of the works were recorded in 2017, featuring the acclaimed American soprano Lisa Willson, among other international singers, in both solo and choral performances.

Immediately after the Second World War, Botwinik was engaged in retrieving little-known songs of the ghettos and camps that might otherwise have been lost, from art songs to children’s melodies.

Botwinik, whose parents, siblings and other relatives perished, immigrated to Montreal in 1956. He taught music and was choir director at United Talmud Torah and Jewish People’s and Peretz schools for 35 years.

His son Alexander, a lecturer in Yiddish at the University of Pennsylvania, was largely responsible for gaining wider attention for his father’s work and is now producing a second recording.

In the preface to From Holocaust to Life, Rakhmiel Peltz, founding director of the Judaic studies program at Philadelphia’s Drexel University, observed, “Through (Botwinik’s) productivity we learn to appreciate the extraordinary spirit of the survivor generation. He contributed to immortalizing the voices of that generation.”

Son of a watchmaker, Botwinik was born on Dec. 12, 1920 in what was dubbed “the Jerusalem of Lithuania” owing to its importance as a Jewish spiritual centre. He was exposed from the earliest age to the great cantors of the period, and was singing himself in synagogues from the age of 11.

His precocious talent was recognized, but the family was too poor to give him music lessons. On merit, he was admitted to the local conservatory at age 13.

After the war, in Lodz, Poland, Botwinik collaborated with the partisan and poet Shmerke Kaczerginski in interviewing survivors and transcribing hundreds of songs that were published as a book in 1948. Some made their way into the repertoire of prominent cantors, such as Louis Danto, also a concert performer.

Botwinik then went to Rome where he continued his studies at Santa Cecilia Conservatory. There he met his late wife Silvana Di Veroli, an Italian Jew who had survived the German occupation hidden in a church.

In a condolence, Murray Kurtz, a former elementary school student of his in the 1960s, recalls, “Even though we were just kids with little talent or attention span, (Botwinik) treated and instructed us as if we were serious singers and musicians. He demanded that we work hard and improve.

“We may not have appreciated it at the time, but we did so years later when we found out our teacher was in fact a famous composer.”

Botwinik never gave up his fight to see Yiddish once again spoken daily. In a 2011 interview for the Massachusetts-based Yiddish Book Center, the nonagenarian gave a forceful argument for the reinvigoration of his mother tongue, deploring that it was taught less and less in Jewish schools.

“First of all, we must be stubborn and… it needs to begin with the youth. This will determine if Yiddish will continue to exist. If, heaven forbid, something happens, that it is thrown away, then we are abandoning an inheritance.”

Predeceased by his wife and son Morris, Botwinik is survived, besides Alexander, by children Riva, Leon and Jack, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

David Botwinik Remembers Joining a Choir in Lithuania as a Young Boy

Becoming a Cantor at the Age of Eleven in Vilna, Lithuania

Antisemitic Violence in Poland after World War II