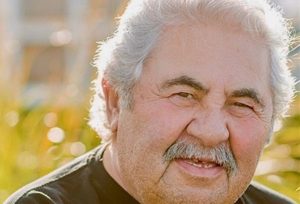

Yehudi Lindeman, who died in Montreal at age 84 on June 12, was well into middle age before he was able to frankly confront what it meant to be one of the youngest survivors of the Holocaust, and the responsibility that came with that.

The Dutch-born Lindeman was the founder and director of Living Testimonies, a video archive of survivors’ accounts of their experiences, one of the first of its kind when it was launched in 1989 at McGill University.

He came to realize that older survivors, who had the most vivid memories, were not going to be around forever to bear witness to history and their stories had to be preserved and made publicly accessible.

With a minimal budget and team of volunteers, Lindeman, a professor of English at McGill, conducted hundreds of interviews through the 1990s with survivors living in Montreal, which had the third-largest survivor community in the world.

Born in Amsterdam in 1938, Lindeman, an only child, was sent away by his parents in 1942 to be hidden in the countryside. He would be shuttled between at least 15 rural locations until the end of the war.

After liberation Lindeman was reunited with his mother, Bets, who survived by posing as a gentile. His father Nico, who was in the Dutch resistance, had perished, as did over 100 other family members.

Lindeman said his memory went “psychologically underground,” and for more than 40 years he never thought about his time in hiding, a repression he would learn was common among child survivors.

Of his time eluding the Nazi occupiers, he said, “The only sense of stability I felt was when another stranger—a courier working for the resistance, no doubt—would take me once again to a new place, usually on the back of a bicycle at night.”

After attending the University of Amsterdam, he pursued a PhD in comparative literature at Harvard and began teaching at McGill in 1971. He would earn a reputation as an accomplished scholar of Renaissance poetry, among other erudite topics.

In the early 1980s, the sight on television of women gathering daily in Argentina to plead for male relatives who had “disappeared” under the brutal military regime, he said, may have reawakened his buried childhood trauma and stirred a belated realization of the imperative of remembrance.

In 1986 he saw French director Claude Lanzmann’s monumental documentary on the Holocaust, Shoah, and the power of seeing and hearing survivors speak openly about what they had been through became clear to him.

Although Living Testimonies was based at McGill, Lindeman did not want to produce academic material, but rather capture stories that would bring the Holocaust to the general public in a way that touched them emotionally.

His research culminated with the 2007 publication of Shards of Memory: Narratives of Holocaust Survival, a collection of 25 particularly compelling accounts of loss and resilience. Elie Wiesel wrote the introduction and historian of the Holocaust Robert Jan Van Pelt hailed it, saying the book “frames and informs the emerging debate on the value of survivor testimonies in the post-survivor age.”

In his own video testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation in the 1990s, Lindeman stressed the importance of people of all backgrounds learning about the Holocaust, and for survivors to come forward, no matter how painful, to make that possible.

Until recently, he said, the past for him had been “a very dark place (he) did not want to visit,” but he came to realize it had a positive side as well.

“Most of all, through these stories we tell the world how fast we can go down to a space that is hard to escape from… (they) send out early-warning messages like the little bird.”

Lindeman described himself as “basically an optimistic person,” despite his being among the only 3,900 Jewish children in the Netherlands, out of a community of 150,000, to have lived.

“For my single survival 40, 60, 80 people contributed in some essential way,” he said. “To each one I owe my survival. As a result, I have a very optimistic outlook on humanity.”

Lindeman was a co-founder of the Federation of Jewish Child Survivors, an international network of child survivors—whom he called the “one-and-a-half generation”—in 1990.

The board of the Montreal Holocaust Museum, where Lindeman was formerly a volunteer, stated his “impact on Holocaust remembrance and oral history in Montreal is unparalleled…His profound impact and leadership at the Museum played a key role in influencing how we collect and preserve Holocaust survivor testimony today.”

Furthermore, his organizing of child survivors came “at a time when their distinct needs were not always well recognized or addressed.”

As numerous condolences attest, Lindeman is remembered as a kind and gentle man, gregarious and warm, who loved nature, never lost his wonder at the world, and continued on a lifelong spiritual search for healing and meaning.

Lindemann was also fond of travel and just before his unexpected death he had enjoyed more than a month in Israel visiting friends and family.

Lindeman is survived by his wife Françoise De La Cressonnière and his son David, from his first marriage.