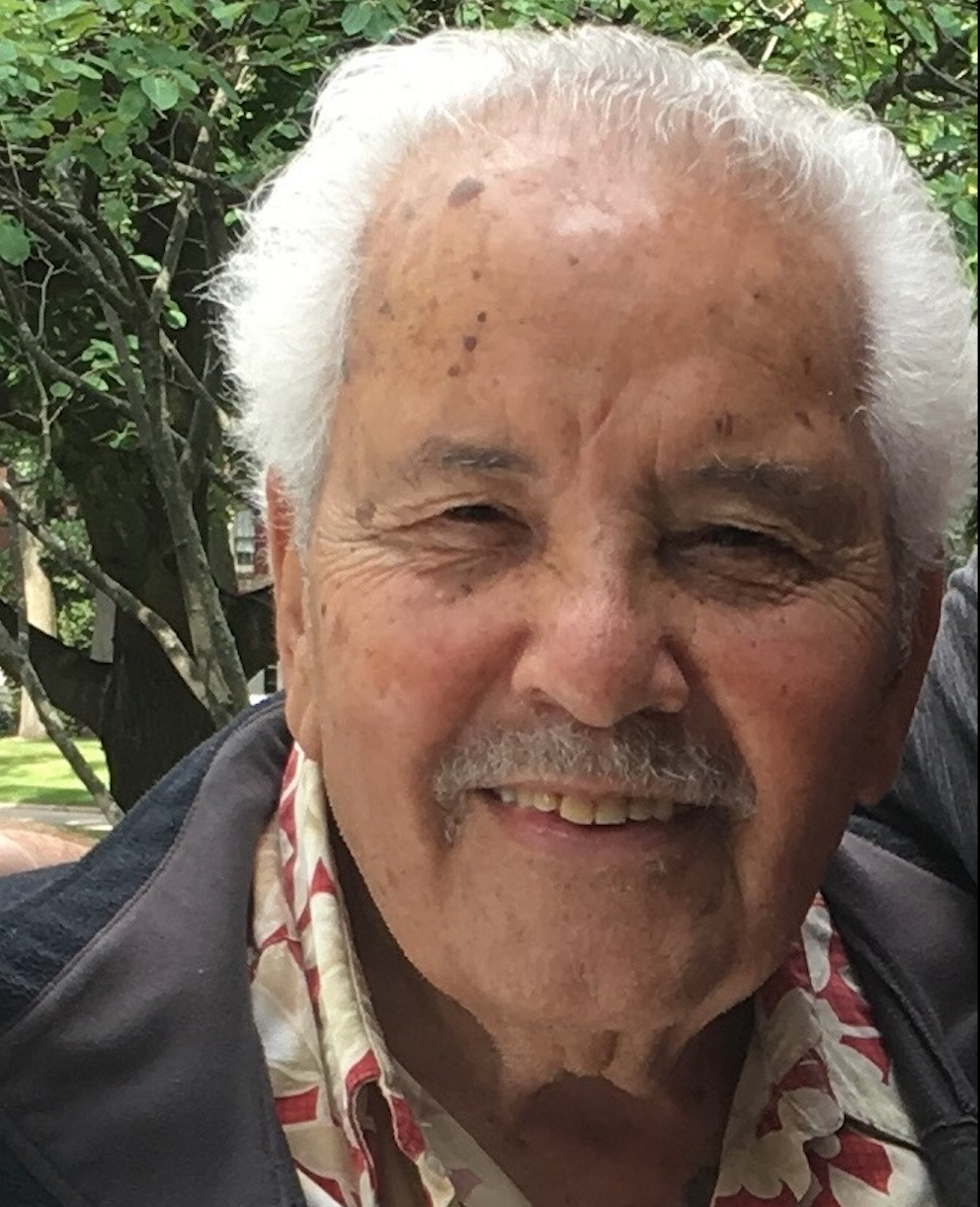

Ben Schlesinger survived the war through the ingenuity of his stepmother, his own faith and initiative and the help of Jewish organizations around the world that serendipitously came at the right time. He became a renowned professor of social work, applying his passion for family to those he helped.

He died in Toronto on July 10. He was 97.

Schlesinger was born in Berlin in 1928 to Abraham, who owned a clothing store, and Esther, who died four days after his birth. His father found a gentile family that was happy to informally foster Ben. On Shabbat he attended the Pestalozzi Synagogue with his father and paternal grandfather and observed Jewish holidays with his father, grandfather and maternal grandparents, aunts and uncles.

In 1931 Ben left the ‘foster’ family to live with his father, his father’s new wife Gizzy and his grandfather. Soon, his brother Joe was born.

As the political situation in Germany changed, Ben remembered much tension in the Jewish community with extensive discussions about the possibility and logistics of leaving Germany and getting visas. His parents considered sending him on the Kindertransport to Britain but changed their minds. “You couldn’t escape the fact that the Nazis were taking over,” he said in a 1998 interview for the Shoah Foundation.

On October 28, 1938, there was a knock at the door, and Ben’s father and grandfather were arrested. They were originally from Poland and were deported back across the border. Schlesinger remembered it was a ‘great shock’, but the family in Berlin initially received postcards that reassured them that both were alive and in their hometown of Bedzin. Ben assumed that they would be returning soon. Meanwhile, the atmosphere for Jews in Berlin was changing rapidly.

“On Kristallnacht, in November 1938, the windows on our store were broken. There were people outside milling around, a lot of glass and an SS man outside. We took out some of the clothing that was left – leather jackets and clothes, loaded the goods onto a truck and took them to a friend’s store.”

Meanwhile Gizzy focused on mastering the German system of paperwork, permits and visas. In late 1939 Ben, his stepmother, and his brother left Berlin for Belgium but soon found themselves fleeing through France as the Germans moved deeper into Europe. During the journey, Ben learned French, survived the bombing of a train that he was on, and admitted to enjoying Belgian chocolate, eventually stopping in Luchon, a spa town at the border of Spain and at the foot of the Pyrenees. Ben’s stepmother heard that the Portuguese consul in Marseilles was giving out visas for passage to Portugal. She procured them, and the family crossed the border and arrived in Lisbon in late 1940.

“There were Jewish refugees from all over Europe in Portugal. The American Joint Committee had a great organization. I was in a Zionist Jewish group for refugees that met every Shabbat, and we also met Portuguese Jewish youth. I enrolled in Lycée Francaise and I had my Bar Mitzvah at the Spanish Portuguese synagogue.

“The Polish government had a diplomatic office in Lisbon, and my mother, who spoke Polish, found out that we could get a visa to Cuba. Or to Mozambique which was a Portuguese colony. She also heard that soldiers’ widows were given preference to leave the country, so she told them her husband served in the Polish army and was killed. By that time, we had also received word that my father and grandfather had died in Auschwitz.

In 1941 Schlesinger’s mother learned that the Canadian government had 400 permits available for non-Jewish ‘Poles in exile’. She was able to get four permits – including one for her sister Bertha who had joined the family.

“The Jewish Agency got us tickets on a troopship, and we boarded the SS Excambion for Bermuda a week before Pearl Harbour was attacked. We arrived in Bermuda and by this time the war had started. We transferred to the RMS Lady Rodney and landed December 1941 in Halifax.

“I spoke German, French and Portuguese but when we got to Montréal I was enrolled in an English public school.” Schlesinger learned the new language quickly. “We registered with Jewish Immigrant Aid Society, and they arranged for us to live with a Jewish family in Montreal I think we were the first group of refugees that came during the war. By the time I entered the last year of public school my mother had started ‘peddling’ stockings door to door often on credit and I would collect. Eventually she opened a dry goods store.”

Schlesinger graduated from Baron Byng High School then pursued an undergraduate degree part time at night while working at an administrative job during the day.

Once he graduated, he found a job with Jewish Immigrant Aid Society as an untrained social worker. The director of JIAS, Joseph Cage, remembered the family and became Schlesinger’s mentor.

He was offered $21.50 per week to work with refugees from the camps. “I didn’t speak Yiddish, but Joseph said some of the refugees wouldn’t like to hear German. So, he suggested, ‘Just speak German with a Jewish accent,’”

His mentor encouraged him to apply to go back to university, and he was admitted to University of Toronto with a small fellowship in 1951. In 1953 he graduated with a master’s in social work and began working with Children’s Aid. In 1957 he was admitted with a fellowship to an intensive and prestigious training program at the Merrill Palmer institute in Detroit which is still at the cutting edge of research and training in child development.

“This program was probably the best thing that ever happened to me. Part of the program was to go through your own therapy. I began going twice a week for about 12 months. My therapist suggested that I talk to my stepmother about the tensions I felt being dragged through Europe. A lot of the time her frustration was let out on me. That’s what happens when you are a refugee and widow, and you’ve lost everything. I was a scapegoat in some sense. I visited my mother and talked about it. I don’t know if it helped her, but it helped me.”

“One of my professors thought I should take a PhD. He was a graduate of Cornell, and he wrote to the dean of child development and family relationships. I applied, thinking, ‘What have I got to lose’? I got the largest fellowship they had.

“Before I moved, I wrote to the rabbi at Hillel Cornell who wanted someone to do counselling with Jewish students in Jewish fraternities. And he wanted me to meet Rachel Aber – her father was a Rabbi at Hillel in Ithica. The first week I’m walking up the hill and next to me is Rachel. Then she turned up in my class. It was just before Rosh Hashana and Rachel’s parents invited me to join them. I started eating there and I kept going for two years and then proposed to Rachel. “

By 1961 Schlesinger and his wife had returned to Toronto and he joined the faculty of Social Work at U of T where he became the first social work professor in Canada to be elected as a member of the Royal Society of Canada.

“Dr. Schlesinger was a distinguished scholar, educator and author whose work profoundly shaped the field of social work in Canada and beyond. His commitment to advancing knowledge and supporting families has left a lasting legacy in the academic and social work communities,” Charmaine Williams, Dean of the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work told The CJN.

“I’m constantly interested in what happens to family life – Jewish and otherwise. I think it’s directly related to what happened to me as a refugee having lost my birth parents,” he said.

In 1988, the City of Berlin invited Schlesinger and his wife back as part of a program for former Jewish Berliners. After 49 years he returned to the city he was born in. And, for the first time he was able to visit his mother’s grave at the Jewish cemetery in East Berlin.

Colleague Bernard Katz knew Ben and Rachel through the Association for Canadian Jewish Studies where they were frequent speakers at annual conferences. He told The CJN, “He had a warm and bright personality and a sense of Yiddishkeit. The two of them were involved in all sorts of different things. My wife and I would go to the Toronto Jewish Film Festival almost every year and Ben and Rachel were volunteers. He was a real mensch.”

“Our father was the patriarch of our family – our hero, our guiding light and a true legend in our eyes. He was loved and respected by all who knew him and his kindness and wisdom touched many beyond our family. His legacy will live on through the generations,” his daughter Esther told The CJN.

“My first message to the new generation is don’t forget,” Schlesinger said. “View our testimonies. Go to Europe and visit some of these places, including the camps. Read. Study. Ask about your family roots. And mainly and above all, keep your Jewish identity. We are very few people – don’t destroy us.”

He leaves his wife of 66 years, Rachel, children Avi, Leo, Esther and Michael and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.