Members of Winnipeg’s Jewish community are welcoming the publication of new research by the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) into its entanglement with National Socialism before and after the Second World War. The MCC is the international humanitarian aid arm of the Canadian and American Mennonite churches.

“I’m pleased and impressed with MCC’s honesty, purposefulness and willingness to come to grips with its past,” said Daniel Stone about the research published in Intersections, the quarterly newsletter of the Winnipeg-based international humanitarian organization.

Stone, a retired University of Winnipeg history professor, was also impressed by the high calibre of the research.

“They have very high standards,” he said of the researchers, “and are willing to say what happened.”

Belle Jarniewski, executive director of the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada, feels the same way.

“I really applaud MCC for the research,” she said, adding “it is important for it to reckon with its past.”

Among the 12 essays in the newsletter is “MCC and Nazism, 1929-1955,” by Ben Goossen, a historian at Harvard University.

In it, Goossen noted that MCC “at best, kept silent” about its involvement with Nazis during that period, and “at worst, was involved in coverup and denial.”

During that time period, “MCC leadership made conscious decisions at many points to work with Nazis where they didn’t have to, and downplayed collaboration with Nazis by some Mennonite refugees,” he said.

Later, it developed a narrative about the rescue of about 12,000 Mennonite refugees from the former Soviet Union that “claimed Jewish suffering, that Mennonites had suffered like the Jews,” he said.

This prevented MCC from taking an honest look at its past, he went on to say, adding that prevented it from “wrestling in any meaningful way” with the Holocaust.

By evaluating the decisions of previous generations of MCC leaders, the organization can develop tools to navigate ethically challenging situations today, he said.

“Responding to evidence of institutional antisemitism within MCC’s history will benefit the organization’s engagement with Jews, specifically, and it will more generally strengthen MCC’s work in a variety of interfaith contexts,” he added.

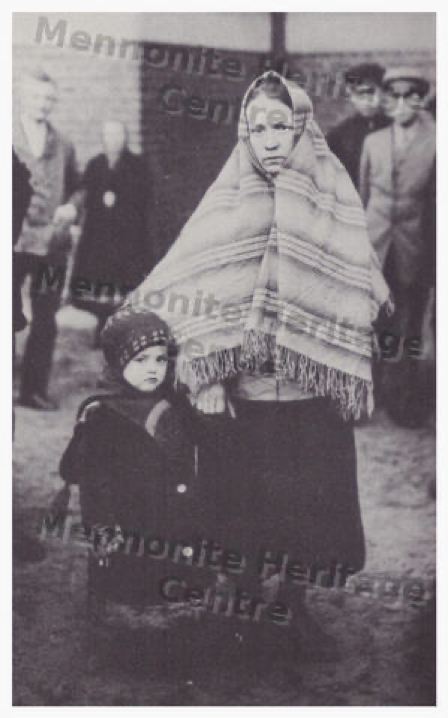

In her essay, “Defining the deserving: MCC and Mennonite refugees from the Soviet Union after World War II,” Aileen Friesen, who teaches Mennonite studies at the University of Winnipeg, noted that defining which refugees were deserving back then was “based on MCC’s own moral framework.”

Although “seemingly without intention to cover acts of atrocity committed during the Nazi period, MCC gave licence for Soviet Mennonites to minimize or erase the different ways they had collaborated with and benefited from the Nazis,” said Friesen.

By taking a hard look at MCC’s wartime past, the agency can “fully address” things that were once hidden and brushed over, she said, adding “We don’t have to be afraid of our past… covering it up is more detrimental.”

Friesen acknowledged for some, Mennonites and Jews alike, “these are painful memories from a painful time.”

But, she said, it can be an opportunity to discover what that experience means for today, and to develop good relations between the Mennonite and Jewish communities.

Mennonite church in Chortitza (mhsc.ca)

Two years before MCC’s public acknowledgement of its involvement with National Socialism, about 175 Mennonites and Jews gathered at Winnipeg’s Asper Jewish Community Campus in November 2019 to hear a presentation titled “Jews, Mennonites and the Holocaust.”

Sponsored by the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada, the event was about the terrible things that had happened 77 years earlier in the Ukrainian city of Chortitza, a place where Mennonites and Jews had lived peacefully for decades.

Then the Nazis came, and everything changed.

In 1941, before the German invasion, Chortitza was home to about 2,000 Mennonites and some 400 Jews, from a total population of about 14,000. A year or so later, all the Jews had been killed by the Nazis.

Did the Mennonites know what happened to their neighbours? And did some help with the killings? Those were the questions addressed that evening by Aileen Friesen and Hans Werner, a retired professor of Mennonite history, also from the University of Winnipeg.

Friesen began by talking about the massacre of Jews in the region in 1942 in the city of Zaporizhia, across the river from Chortitza.

About the same time as 3,000 Jews were being murdered, Mennonites—who were treated well by the Nazis because they were seen as ethnic Germans—were celebrating their newfound liberation from communist oppression at Easter church services.

“The image is stark,” said Friesen, describing how Mennonites benefitted under German occupation while Jews were subjected to “unspeakable violence.”

While most Mennonites didn’t participate in the genocide against the Jews, some did collaborate, serving as mayors, police or other officials. And some were members of local security forces that rounded up and murdered Jews.

For decades, Mennonite scholars “have struggled with the issue of collaboration,” Friesen said. But recent discovery of records from the former Soviet Union provide “concrete evidence” of Mennonite participation in the Holocaust.

Since much of the new material comes from Soviet interrogation records from after the war, it has to be “treated with caution,” she acknowledged.

But together with other historical records and recollections, it is “clear” some Mennonites aided the Nazis in killing Jews.

In his presentation in 2019, Werner dealt with the way the Mennonites have remembered their wartime experience in Ukraine.

Referencing memoirs written by Mennonites after the war, he noted that the Holocaust usually only makes cameo appearances. Most of them focus on Mennonite life before the 1917 Russian Revolution, the subsequent loss and displacement under the Soviets, and their own suffering during and after the Second World War.

These memories are coloured by how the German invasion of Russia was “a relief from Soviet oppression,” he said, adding they also fit neatly into the post-war “Cold War logic,” when the Soviet Union was seen as the enemy.

Some memoir writers who mentioned the Holocaust promoted a sense of “equivalence between the killing of the Jews and Mennonite suffering [under the Soviets],” he said, or blamed the Nazis for their deaths.

Fast forward a year to November 2020, when the American Jewish online magazine Tablet published “The Real History of the Mennonites and the Holocaust“ by Ben Goossen.

Goossen, who grew up Mennonite, detailed some of the ways MCC became entangled with Nazis while helping thousands of Mennonite refugees from the former Soviet Union escape from Europe after the Second World War.

This included employing a refugee and former Nazi supporter, Heinrich Hamm.

In the article, Goossen said if consideration was given only to MCC’s postwar reports about its refugee resettlement work, “we might assume that the denomination’s premier aid organization was acting in good faith—that [MCC’s] leaders were unaware of the Nazi collaboration of refugees like Hamm.”

This reading, he said, “cannot be supported” by research.

“A great gulf looms between the image of Mennonites as a peaceful Christian denomination engaged in humanitarianism and peace building around the world, including in the Middle East, and what historians have begun to reveal about the entanglement of a substantial minority of Mennonites with National Socialism during the 1930s and ‘40s,” he wrote.

“It has included influential leaders within the Mennonite denomination, including within its best-known humanitarian aid organization, MCC.”

A couple of months later, in January 2021, came the book European Mennonites and the Holocaust (University of Toronto Press), a collection of scholarly presentations made at a 2018 conference titled “Mennonites and the Holocaust”at Bethel College, a Mennonite school in Newton, Kansas.

At the book’s online launch, presenters spoke about how Mennonites in the Netherlands, Germany, occupied Poland, and Ukraine were witnesses to, and participated in, the destruction of European Jews.

In his remarks at the launch, editor Mark Jantzen of Bethel College noted that Europe’s 185,000 Mennonites during the Second World War were “neighbours to Jews, eyewitnesses to deportations, and in some cases, to mass murder.”

They were also beneficiaries, enablers and perpetrators of the Holocaust, he said, adding that some were rescuers “less frequently.”

The public memory of that experience, he said, has typically been to see Mennonites as victims and “moral heroes…on the right side of history.” That story is “terribly incomplete.”

Reflecting on the published research, Alain Epp Weaver of MCC, who edited the special issue of Intersections on the topic, said the organization is “very grateful to the historians for helping us understand how MCC was entangled with National Socialism.”

Through their work some “sobering facts have emerged and been heard,” he said, adding the organization is committed to being “open and transparent” about this episode in its history.

This includes how Mennonites at that time were “bound up” in the broader Christian experience of antisemitism.

MCC’s goal now, he said, is to assess what it can learn from that episode in its history, at the same time emphasizing it “firmly opposes antisemitism alongside all forms of racism.”

The organization is committed “to continued examination of its history and to discerning how to respond to this history in ways that are faithful to its grounding in the gospel of reconciliation.”

* * *

As that November evening at Winnipeg’s Asper Centre in 2019 was concluding, Dan Klass, a member of the local Jewish community whose parents came from the Chortitza region to Winnipeg in 1913, noted the similarities between that community almost 80 years ago and his home now.

As it was back in the early part of the last century, Winnipeg today is a mix of Mennonites and Jews, he said, noting relations between the two communities are good—despite their terrible history.

“We should celebrate and cherish this, and make sure Winnipeg is a place where it never happens again,” he said.

John Longhurst is the religion reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Information in this article is taken from stories he has filed to that newspaper about this topic. The full report about MCC and the Holocaust can be found at this PDF link.