His father was a tailor, all his uncles were tailors, and he was determined not to be a tailor.

But being a tailor not only saved Irving Leibgott from almost certain death during the war, but also served as his passport to a new life in Canada as part of The Tailor Project.

Leibgott died in Montreal on July 1 at age 100—making him one of the longest-living members of that group of Holocaust survivors.

Leibgott was born in Plock, Poland. His mother, Chaya, looked after Irving and his sister Sonia. His father, Avraham, owned a lucrative business making suits.

“My father always said it was a big deal. He had people working for him. It was a little factory,” Irving’s son Jeffrey told The CJN.

Leibgott worked part time at his father’s company—but when war broke out, all tailors were sent to a nearby factory to make and repair German uniforms. By 1941 the factory closed, the local ghetto was liquidated and Leibgott’s family was transferred to the small town of Sucanev where there was no work and little food.

Leibgott’s father left Sucanev to seek work in Starachowice, a larger city nearby, where he found a tailor from Lodz who custom made uniforms for German officers. Irving soon joined him.

Several months later, the Nazis rounded up the Jews and asked those who were working in factories to step forward. Avraham pushed his son forward, convinced that whatever was going to happen might increase their chances of surviving. It was the last time Irving saw his parents.

Irving was sent to a munitions factory but soon, the tailor from Lodz persuaded the Nazis to release him so he could help in the uniform factory. By the end of 1943 Irving was forced to leave the uniform factory and eventually he was sent to a sawmill where his sister and her husband worked. Soon all the Jews there were packed into trains and sent to Auschwitz.

He was young and healthy and was assigned to an easy job of stuffing burlap bags with clothing to use as boat bumpers. He managed to survive and as the Russians advanced, Auschwitz was liquidated. In April 1945 after marching to various camps with little to no food, he arrived in Dachau and on April 30 he was liberated.

Leibgott and his brother-in-law Heniek were together in the camps and after liberation and a month-long search they found his sister Sonia who had spent the end of the war in Bergen-Belsen.

From 1945 to 1947, the family of three stayed in the small village of Kaunitz with a group of other survivors trying to forge a path forward. “They were applying to different places, Israel, Canada, the United States, waiting for papers to come through,” daughter Karen Baron explains. Then he heard about The Tailor Project.

Historian, researcher and author Paula Draper told The CJN how the plan came to fruition.

In 1948, Canada was not interested in letting Jews into the country. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s government made it clear that ‘none is too many’. But there was a great need for labourers in Canada.

“People were coming over who were doing manual labor, working in the forests, in mines, and on farms and these projects were bringing over large numbers from DP camps but they were not bringing in Jews. The Jewish community looked at this and said, ‘Let’s approach the government with something that will bring in a lot of Jews,’” Draper said.

Because there were so many Jews in the garment industry, community organizations identified Jewish-owned garment manufacturers who were willing to cooperate. The Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Labor Committee devised a program called the Garment Workers Scheme which became The Tailor Project. They proposed to C.D. Howe, the minister of reconstruction, that 2,000 workers and their families be admitted to Canada. They would work for manufacturers in Montreal, Winnipeg and Toronto and costs would be shared by their employers, the Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society.

A five-person delegation was created to visit the DP camps in Europe and interview applicants. “They thought 90 percent of the people they brought in would be Jewish but as soon as they got approval for this, the government woke up, realized that they didn’t want so many Jews in Canada and reduced it to 50 percent.” Draper explained.

The contingent adopted a ‘half a loaf is better than none’ attitude and departed for Europe. Eventually the government approved admitting 2,136 tailors.

“There were posters advertising that the Canadian government and the unions needed tailors, so I applied.” Leibgott explained in an interview published in The Tailor Project. “The test was a little nothing. They just wanted to see if you could hold a needle and thimble and sew a little. It was very easy.”

“The idea was to get them in and help them get a foothold in Canada, but the community wasn’t organized in terms of helping survivors and they didn’t understand them,” son Jeffrey told The CJN. “The Jewish community who came over before the war spent years trying to assimilate and be accepted. And here come all these ‘greeners’ with their accents and their customs. There was almost an embarrassment. After surviving the Holocaust and finding their way to Canada their own Jewish community didn’t exactly welcome them with open arms.”

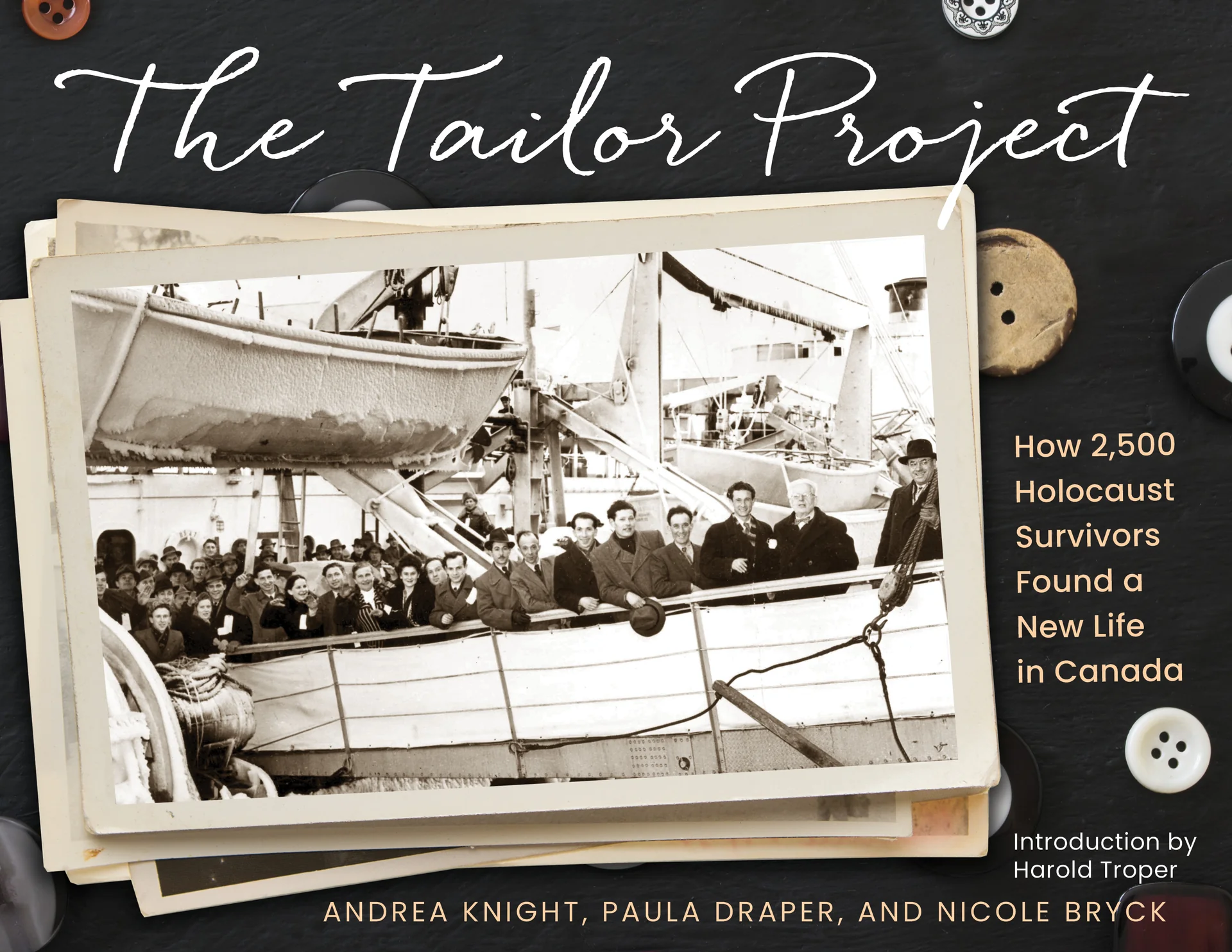

“I didn’t know anybody when we started out from Kaunitz, but I met someone just before we went on the boat who became a lifelong friend. We ended up opening a valet tailoring service and worked together in Montreal for 40 years,” Irving Leibgott told the authors of The Tailor Project.

He arrived in Montreal on a Friday and the following Monday started work in a men’s clothing factory.

“You came to Montreal with $10 in your pocket, one month lodgings paid and a factory job you hated. You couldn’t speak the language and only knew the people you met on the ship, some of whom became lifelong friends,” daughter Karen eulogized. He earned $25 a week and saved to bring Sonia, Heniek and their new baby to Canada.

Eventually Irving and his partner bought a valet tailoring service. Over the years it grew and moved to different locations but settled on Stanley Street, in downtown Montreal, where it flourished for more than 20 years. “We didn’t become rich, but we were making a better living and had a better life than I would have had in the factory,” Leibgott said in an interview.

He met his wife Mary through a friend who was a furrier. “Her parents, Sarah and Sam Pinkus embraced my dad. They were Polish but arrived in Canada before the war and wanted to know every detail of what my dad went through. It was almost part of their courtship,” Karen explained.

“My father didn’t live in the past. He didn’t brood. He lived a long, beautiful life. He was a realist. And he was resilient. He had to be.”

Irving was pre-deceased by his wife Mary. He is survived by his children Jeffrey, Karen and Brian, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

According to Paula Draper, Jewish survivors comprised just 10 percent of the 165,000 displaced persons who arrived in Canada between 1947 and 1953. Including dependents, approximately 6,000 Holocaust survivors came to Canada through The Tailor Project. Watch a nine-minute documentary on the project below: