The name of Fl. Sgt. Joseph Rabiner was recently added to the RCAF Memorial Airpark at the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, Ont.

Rabiner was killed in action when his RAF Mosquito disappeared without a trace at the end of March 1945, on a night-time raid to Berlin. The young Montreal salesman was 21, and had been serving as navigator with the RAF 692 Squadron, out of RAF Graveley.

DONOR ISN’T EVEN RELATED

The story of how Rabiner’s name became part of the museum’s 12,000 Ad Astra memorial stones is unusual because the donor who arranged it isn’t even related to Rabiner.

But John Chisling, a resident of Wellington, Ont., has devoted many years to keeping the memory of the young airman alive, because he considers Rabiner “family.”

It’s complicated, but here goes:

Joseph Rabiner’s father had died before the war. His mother Rebecca died around the time that her son shipped out to England.

Rabiner’s older sister, Doris, still lived in the family home on 17 Villeneuve Ave. E., in Montreal’s old Jewish area. Her brother’s personal effects were sent home once the air force declared him missing.

Doris Rabiner married Harry Rubin. But the marriage was brief, and the couple divorced.

According to John Chisling, Doris moved to California to start a new life.

Harry then went on to marry again, to Jenny Chisling of Nova Scotia: John Chisling’s aunt.

And no one wanted Joseph Rabiner’s personnel effects, which is how he got them.

Dedication ceremony at National Air Force Museum of Canada in September

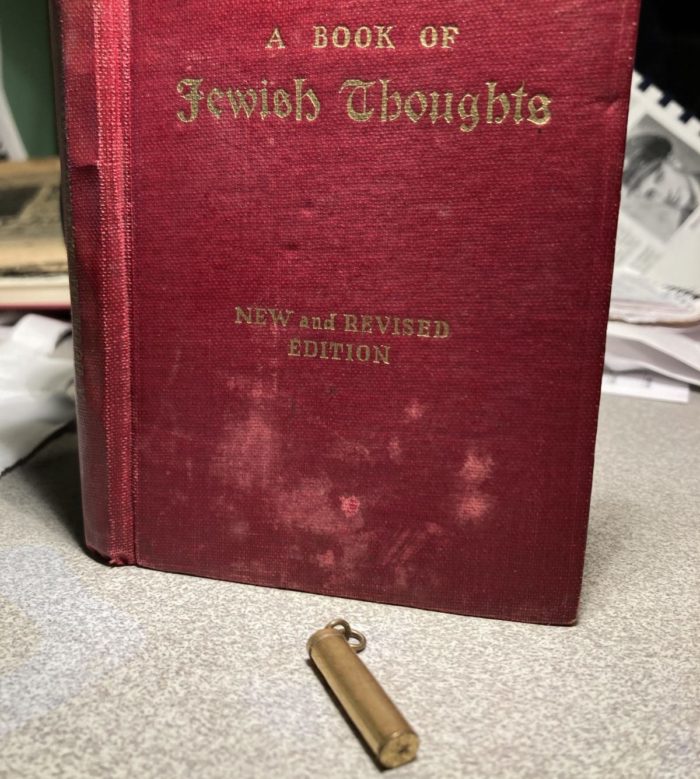

Chisling has lovingly kept Rabiner’s military-issue Book of Jewish Thoughts, handed out to Jewish personnel overseas by the corps of Jewish chaplains. This one was signed by chaplain Rabbi A.M. Babb, of Saint John, N.B.

Chisling also had Rabiner’s gold mezuzah, designed to be worn on a chain around the neck.

The dedication of the granite stone for Rabiner took place on the last Saturday of September 2022, as part of the National Air Force Museum of Canada’s annual Ad Astra ceremony.

The grey monument bears Rabiner’s name, the years of his birth and death, his hometown, and the RCAF symbol.

Trenton may be one of the few places in the world where the young man is remembered. His name is inscribed also at Montreal’s YMHA and on the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s Runnymede Memorial panels in Surrey, England, in tribute to 20,000 Second World War personnel who have no known grave.

WANTED TO SEE ACTION

Joseph Rabiner was born in 1923. His parents had come to Canada from Eastern Europe, but his father Aaron Rabiner, a tailor, died when his son was just 15. Joseph attended Montreal’s Baron Byng High School, but left early to work in the garment district.

When he was 19, he joined up.

He told the recruiters he would have done so earlier but as he was the only boy at home, with a sick mother, he “had to wait until he received his army call up.”

He admitted that his mother had wanted him to take a safer job with the RCAF, as ground crew. But he was determined.

“Very insistent on air crew. Wants to see action,” his military records show.

After 18 months of training in Canada, Rabiner was shipped over to England: he arrived in July 1944, shortly after D-Day.

More training in England was next, until February 1945. Then, he was posted to the RAF’s 692 Mosquito squadron, to work as the other half of a two-man crew.

Soon, he had flown nearly enough missions over German-occupied Europe to get away from the front lines.

Newspaper reports at the time of his death quoted a letter he’d written home:

“If all goes well, I should be home by the end of July.”

He talked about what it was like being part of a Mosquito crew: flying in the fastest combat aircraft in the skies, carrying 4,000-pound bombs and coming in low over the target, without defensive weapons.

“We fly in anything. We even have a song: ‘I walk alone-I fly alone.’”

How I came to have Rabiner’s possessions

Before the pandemic, in 2019, John Chisling came to one of my public talks, in Picton, Ont. I am a regular speaker about my book Double Threat which tells the story of the 17,000 Jewish Canadians who served in the Second World War.

Chisling made sure to bring Rabiner’s religious artifacts with him that day. He was eager to share the young man’s story, and detail his own search for any descendants of the Rabiner family.

The sister Doris remarried a man named Fifer, in California. They had a daughter, who Chisling would very much like to track down.

In July 2021, a parcel was left in my mailbox. It contained not only Rabiner’s wartime Jewish book, but also a gold mezuzah. And a 1944 letter from a friend of Rabiner’s, Lawrence “Sonny” Serchuk, informing him that his mother had died.

I knew that friend’s name: he was my grandmother’s cousin.

John Chisling didn’t know that eerie connection.

But he told me why he had decided to loan Rabiner’s possesions to me: he wanted me to display Rabiner’s personal effects every Remembrance Day.

“It’s comforting to me knowing you have the prayer book of a Jewish young man in his twenties, who died with another, hurtling through a night sky, at great speed, willingly, for a greater purpose,” Chisling wrote in an email.

Due to the pandemic, for the past two years we have observed Remembrance Day mostly virtually.

But this Sunday, for the first time, I will take both of Joseph Rabiner’s items with me to an in-person service to remember the Canadian Jewish veterans and honour those nearly 450 who didn’t come home.

The event is being held beginning at 9 a.m. at Kiva’s Restaurant, in Toronto, on Sunday Nov. 13. The service then moves to the Jewish cenotaph at Mount Sinai Cemetery at 986 Wilson Ave., beginning at 11 a.m.

Author

Ellin is a journalist and author who has worked for CTV News, CBC News, The Canadian Press and JazzFM. She authored the book Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military and WWII (2019) and contributed to Northern Lights: A Canadian Jewish History (2020). Currently a resident of Richmond Hill, Ont., she is a fan of Outlander, gardening, birdwatching and the Toronto Maple Leafs. Contact her at [email protected].

View all posts