Ron Csillag, reporter emeritus with The Canadian Jewish News, offers a new special report we’re publishing in tandem with Holocaust Education Week: Nov. 4-10, 2024—featuring insights from Dr. Frank Sommers of University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

Like a stethoscope to the chest, Canadian medical schools are hearing the echoes of the Holocaust.

They are coming to terms with the solemn oath doctors take at the start of their careers, “First, do no harm,” and are teaching the unspeakable horrors their forerunners were capable of—and executed–in shocking violation of that oath.

It is still a matter of great mystery and revulsion that doctors in Nazi Germany were centrally complicit in the Holocaust, routinely trampling on their ancient Hippocratic Oath by conducting sadistic experiments on concentration camp inmates and murdering the weak and disabled, all in the cause of perfecting the “master race.” Society’s revered healers became killers who willingly, even enthusiastically, did the Third Reich’s bidding.

Why the perversion of medicine on such a scale and the lessons drawn from it has not been a compulsory part of medical education until fairly recently is also a mystery. But over the past few years, just about every medical school in Canada has put instruction about the Holocaust and its accompanying ethical issues if not on the front burner, then at least on the radar.

The resulting issues are especially relevant as campuses across the country have experienced spikes in antisemitism in the post Oct. 7 world.

Medical schools are also finding that exploring doctors’ roles during the Holocaust is opening the door to examine how other minorities, including Indigenous people, the homeless and immigrants, are treated by the medical system today.

The campaign to get Holocaust education into medical schools in Canada was spearheaded by Dr. Frank Sommers, a Toronto psychiatrist, professor at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine, and a child survivor of the Holocaust. Born in Budapest in 1943, just months before the Nazi invasion of Hungary, Sommers, his mother, brother and a few close relatives survived by hiding in the basements of bombed-out buildings in the city. The rest of his family was murdered in Nazi death camps.

The impetus for educating doctors-in-training about the Holocaust and its modern implications came from The Lancet, among the most prestigious medical journals in the world. In 2019, editor-in-chief Richard Horton published an editorial titled “Medicine and the Holocaust—It’s Time to Teach” that urged medical schools to integrate Holocaust education into their curricula as a way to explore ethics and leadership but also as a bulwark against antisemitism. “By including the Holocaust in the curriculum of health professionals,” Horton wrote, “medicine could do much to vanquish the evil that is antisemitism.”

Spurred by a longstanding passion for Holocaust education and that Lancet article, Sommers, who co-founded Doctors Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (DARA), wrote an “especially personal” motion to put before a meeting of the Ontario Medical Association in late 2019, calling on the OMA to add the Holocaust to medical education. “By passing this motion, hopefully unanimously, we are adding our voices, resolve and commitment to bring to life the words: ‘Never again—any time and place,’” Sommers read.

“I had no idea what kind of reception the motion would have,” he told The CJN earlier this year, when the subject acquired new resonance in the wake of reactions to the events of Oct. 7. “I had a seconder.” Here his voice broke and he paused. “There was no need for the seconder to speak.” The measure passed unanimously. “The room broke out in applause,” he recalled. “That was so heartwarming.”

University of Toronto

At the Temerty Faculty of Medicine, where Sommers teaches, all this was a call to action. Administrators tapped two young Jewish doctors, Ariel Lefkowitz and Ayelet Kuper, among others, to help guide the creation of a new lecture focused on Holocaust education. UofT thus became the first medical school in Canada to teach the subject.

A few weeks later, in 2020, Lefkowitz, the grandchild of Holocaust survivors, found himself preparing to speak to a class of second-year medical students on “Physicians, Human Rights, and Civil Liberties: Lessons from the Holocaust.”

In an online article from late 2020, he pondered what it meant to apply the lessons of the Holocaust to modern healthcare. “It’s more than simply promising not to commit genocidal acts. Dehumanizing discourse is a significant problem in Canadian hospitals, as certain groups of people are cast as less valuable than others or at fault for their misfortune, including the homeless, Black and Indigenous individuals, those with addictions, and those who don’t speak English.”

Since its launch, the Holocaust session was expanded from one hour to two, and has received positive reviews from students, Lefkowitz told The CJN.

Teaching the subject has “profoundly” affected Lefkowitz’s personal and professional life, in much the way he’d predicted at the start of the process. “Every day, I feel like I am applying its lessons to identify and challenge dehumanizing attitudes, especially towards marginalized patients.”

Whether it is patients with dementia, developmental delays, language barriers, or any condition that marginalizes them in the hospital, Lefkowitz strives “to ensure equitable care by confronting biases and fostering open discussions with colleagues and trainees.”

In the same vein, the concept of moral courage “resonates deeply in medical practice… I always try to advocate for [those] grappling with moral dilemmas and stand up for those in need.” Reflecting on these teachings “has helped me develop as a physician and as an educator.”

He noted a personal symmetry: Two weeks after his initial lecture, Lefkowitz’s daughter, Roey Belle, was born and named for his grandmother, Belle Feig, a Holocaust survivor.

Neither The Lancet nor Sommers were quite done with the subject. In January 2021, the journal launched “The Lancet Commission on Medicine and the Holocaust.” The 74-page report recommended that “Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust” be a mandatory part of health sciences curricula, partly to help medical professionals oppose antisemitism, racism and other forms of discrimination, but also “to embrace and defend our shared humanity in their professional roles as global citizens.”

Around the same time, Sommers launched a quest to spread the word in Canada by writing to the deans of every medical school in the country to “heed this call” by providing instruction in the Holocaust and its ethical lessons for doctors. The replies were almost uniformly encouraging.

***

University of British Columbia

UBC Faculty of Medicine said in a statement to The CJN it “strongly supports education on the Holocaust for learners in the medical and health professions.” This work is in collaboration with Vancouver’s Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC) and Dr. Robert Krell, a child survivor of the Holocaust, professor emeritus of psychiatry at UBC, and long-time proponent of Holocaust education in medical curricula. Last year, the faculty partnered with VHEC to launch a webinar, “It Starts With Us: Contextualizing and Educating about the Holocaust” to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27. For this year’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day, students, faculty and staff were encouraged to read the findings of The Lancet Commission on Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust; watch a webinar on the commission’s work; and view the “It Starts With Us” webinar. Going forward, the faculty plans to continue working with the VHEC on Holocaust education, including the development of a three-part “meta-curriculum” on “dehumanizing discourse” that will begin with lessons from the Holocaust.

University of Alberta

The College of Health Sciences, following a review, will be incorporating Holocaust education into its lecture on Research Ethics.

University of Calgary

Cumming School of Medicine last year expanded teaching in the area of health equity, anti-oppression, anti-racism, Indigenous health, and EDI (equity, diversity and inclusion), as well as specific “small group” sessions on genocide that include the lessons of the Holocaust.

University of Saskatchewan

The medical school’s newly-expanded Year 4 “critical ethics forum” now includes discussion around the role of physicians and scientists in the Holocaust.

University of Manitoba

Max Rady College of Medicine “is moving rapidly to develop an antiemitism and Holocaust education curriculum,” college dean Dr. Peter Nickerson said in a statement to The CJN. “We are engaging multiple stakeholders and anticipate rollout of several hours of curriculum” for this academic year, he added.

McMaster University

The Faculty of Health Sciences, in Hamilton, Ont., in a 2021 letter to Sommers, said it was “certain” to support the campaign to teach medicine and the Holocaust to physicians and physicians-in-training. But in an update to The CJN, the university said there are “active discussions to navigate additions to [its] medical curriculum in a trauma-informed manner, including antisemitism in healthcare. At this time, education about the Holocaust has not been added to the medical curriculum.”

Northern Ontario School of Medicine

NOSM in Sudbury, Ont., is where topics on medicine and the Holocaust are taught in a course called “Ethical and Legal Aspects of Medicine.” These include “medical abuses,” such as the Nazi experiments, the euthanasia operation and sterilization laws, as well as concerns about “misuse of new medical technologies.” Also explored are the creation of post-war codes of conduct and research protocols, including the Nuremberg Code, a set of principles for human experimentation; the Physician’s Oath (Geneva, 1948), which modernized the Hippocratic Oath; international standards on informed consent; and the patient’s right to refuse treatment. NOSM also looks at the looming question of how and why the medical profession in Germany supported and influenced the Nazi regime.

University of Ottawa

The faculty of medicine said it would again have a workshop on “the medical atrocities of the Holocaust” and was reviewing its curriculum with a focus on anti-racism.

Queen’s University

Queen’s Health Sciences in Kingston, Ont., “is dedicated to offering its students an inclusive, diverse and equitable curriculum and learning environment that emphasizes social accountability,” a statement to The CJN said. “A curricular review of the equity, diversity and inclusion content within our MD program is underway.” Further details were not available at press time.

Western University

The medical school in London, Ont., has medical ethics as a requirement of the MD program and students learn about ethics in a variety of contexts. Since last year, a session on medical ethics and the Holocaust has been included in the “Professionalism, Career and Wellness” curriculum for fourth-year medical students.

Université Laval

The faculty said although it is sensitive to the role the medical community played in the Holocaust, “we consider that our current curricular content in ethics meets our program’s pedagogical objectives.” However, officials say they will consider including explicit references to the Holocaust in the future.

McGill University

The medical school said in late 2022 that it was “actively working” on changes to its curricula “regarding the issue of genocide and the role played by physicians in facilitating and perpetrating crimes against humanity. As doctors notoriously carried out such crimes during the Holocaust, it is a major focus of our work.” In a later statement to The CJN, a spokesperson said medical students are exposed to examples of medical abuse from around the world, ranging from the Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis in Black men in the United States, to Nazi sterilization programs “to demonstrate how discrimination negatively impacts health outcomes for patients and population subgroups over history.” Also on the agenda are “basic principles of ethics as they relate to patients of diverse religions.”

Université de Montreal

Sommers received an especially substantive response in early 2023. Since the fall 2022 semester, during the first-year history of medicine course, a section is devoted entirely to incorporating lessons of the Holocaust and the role doctors played in it. Themes covered are eugenics and “hierarchy, obedience and power.” Last year, medical students were offered a conference titled “Medicine and the Shoah, What Relevance for Today?” Margaret Henri, director of the MD program, said the emphasis is not only on the role of medicine and doctors during the Holocaust, but also on “the social context that led to it.” Learning is through targeted readings, discussion workshops, and the writing of a “self-reflexive” text.

Dalhousie University

At the medical faculty, a new seminar entitled “Ethical Research Practice” was added to the syllabus last year. It addresses research ethics during the Holocaust, including considering the “problematic history of research on, as opposed to with, marginalized people.”

Memorial University

The school in St. John’s, Nfld., said its curriculum addresses medicine in the Holocaust “at various points” throughout the undergraduate Medical Education program. This “very important topic” is covered in sessions on the history of medicine and more so within sessions on ethics.

***

International medical schools

In the United States, only about 20 of the 140 or so medical schools, or 15 percent, teach anything about the Holocaust, and that may mean only a single lecture, according to the Houston, Texas-based Center for Medicine After the Holocaust.

Given universities’ current preoccupation with diversity, equity and inclusion, “the world is divided into oppressors and the oppressed, and Jews are the oppressors,” said a dejected-sounding Dr. Sheldon Rubenfeld, founder and executive director of the 14-year-old centre. These days, lamented Rubenfeld, teaching about the Holocaust at American universities “is a tough sell.”

One notable effort in the United States is the Center for Medicine, Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles. The program brings together international scholars “of all disciplines to expand knowledge about the activities of medical professionals before, during and after the Holocaust, and other genocides and human atrocities,” states its website.

One might think the Holocaust’s legacy is compulsory teaching at Israel’s six medical schools but that’s not the case, according to Prof. Shmuel Reis of the Center for Medical Education at Hebrew University’s Faculty of Medicine.

Only the Goldman Medical School at Ben-Gurion University requires study of the subject, in a semester course that began two years ago. Three medical schools, Hebrew University, the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine at Bar-Ilan University, and the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine at the Technion, offer just an elective course. Tel Aviv University’s medical school has but one lecture. The medical school at Ariel University has no dedicated teaching on the Holocaust.

Reis told The CJN that Israeli medical schools need to be brought in line with the recommendations of The Lancet’s Commission on Medicine and the Holocaust, which he co-chaired.

He noted that as well, there are about 30 nursing schools in Israel, with only two or three teaching “MNH”—Medicine, Nazism and the Holocaust.

***

Physicians’ participation in the Holocaust

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Germany, was the first country to enforce a mandatory ethics curriculum in all its medical schools, noted a past issue of the Canadian Journal of Physician Leadership.

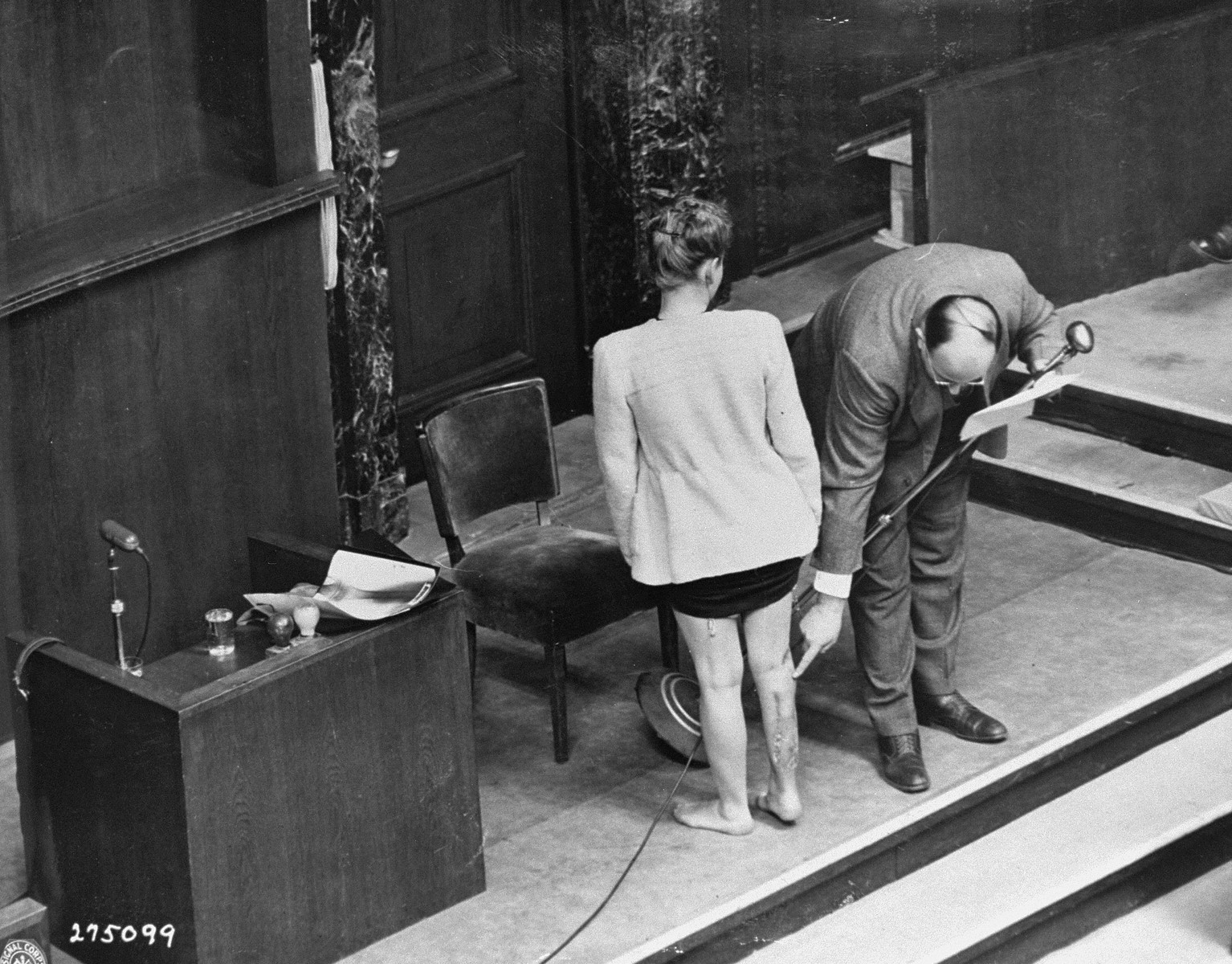

Two areas that medical schools will likely study are why Nazi doctors became such efficient killers and whether they got away with their crimes. The answer to the latter was seen during the postwar Nuremberg trials of Nazi officials.

In the “Doctors’ Trial,” 20 of the 23 defendants were physicians accused of involvement in human experimentation and mass murder under the guise of euthanasia. Seven were acquitted and seven were sentenced to death. The remainder received prison sentences ranging from 10 years to life.

The paradox of how healers became murderers is one for the ages.

Robert Jay Lifton, a U.S. psychiatrist and author of the gold-standard 1986 text on the subject, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide, offered a few possibilities, including that German doctors came to view mercy as weakness and were seduced into becoming “biologic soldiers” bent on strengthening the Aryan genetic strain and eliminating the undesirable. Visions of a pure, disease-free, robust Volk danced in their heads.

Or they just succumbed to the madness, as did millions of other “ordinary” Germans.

Dr. Timothy Holland, a leading Canadian bioethicist and head of the Department of Bioethics at Dalhousie University’s Faculty of Medicine in Halifax, also reflected on how and why German doctors became Nazi killers, in response to questions from The CJN.

“Physicians in Nazi Germany were not simply following orders out of fear. They were complicit in Nazi ideology. Physicians in Germany, as well as in Canada, Great Britain, the United States, and other Allied countries, were enthusiastic about eugenics, which significantly contributed to Nazi ideology. Some physicians saw eugenics as applying medical science to solve societal problems. This mindset could lead to a perversion of ethics, allowing them to commit horrendous crimes while believing they were doing important work to “cure” humanity.

“After the Holocaust’s atrocities were exposed, medicine faced a reckoning, leading to the patient-centered focus we see today. However, this was not the first or last time a shift in medical ethics led to disastrous outcomes. In Canada, countless crimes were committed by physicians who thought themselves ethical.

“Indigenous peoples’ experiences, including the sterilization of Indigenous women, illustrate how physicians can commit horrendous crimes. We must remain vigilant to our Code of Ethics and Professionalism to avoid repeating past errors. This is why it is crucial for medical students to study physician involvement in the Holocaust and other historical medical crimes.”

Sommers, now 81, who still has a busy psychiatric practice and who teaches at the University of Toronto, agrees that getting medical schools in Canada to pay attention to the Holocaust and its myriad lessons has been no small task, but the breakthroughs have been welcome.

“I hope that’s my legacy,” he said. “The least I could do as a child survivor was to push all (medical) schools to teach our future doctors the slippery slope of a fading moral compass. And it’s the least I can try to do for those who cannot speak for themselves.”