Eighteen years after his death, Mordecai Richler is attracting fresh attention from scholars, publishers and, his admirers hope, the public.

A recent two-day conference at Concordia University brought together Canadian scholars, family members and others who were interested in seeing that the writer’s legacy takes its rightful place in the annuls of Canadian literature.

The title of the conference, Mordecai Richler Against the World, may point to why he is not as revered as some believe he should be. Indeed, the contrarian, often caustic nature that exhibited itself most acutely in his later essays on Quebec nationalism appears to have cost Richler the canonization of his memorable novels that uniquely capture the Jewish Montreal of the era.

To his knowledge, as recently as 2010, not a single Canadian university listed a Richler book in its syllabus, said Jason Camlot, the Concordia English professor who heads the Richler Library Project, which organized the conference.

Fellow English Prof. André Furlani said that, “Although he is so read and discussed and controversial, Richler’s popularity is not adequately registered in the academy itself. There is not a lot of academic interest.”

Questioned later on why that is, Furlani replied, “His satirical vehemence, he was just so controversial, and we so wish to avoid that in Canada.”

Camlot said that is changing at Concordia and elsewhere.

Richler’s literary executor, prominent Toronto entertainment lawyer Michael Levine, is trying to ensure that the author does not fade into oblivion.

He is the one who urged the Montreal publisher Editions du Boréal to translate Richler’s five major novels into French over the past five years, in an effort to reach a new audience, particularly in Quebec.

“The only thing the Jewish community and francophone community agreed on was that Mordecai was the devil incarnate,” said Levine.

The demonization of Richler reached a fever pitch after his scathing, sarcastic critique of Quebec’s language laws in The New Yorker in 1991, followed up by the book, Oh Canada! Oh Quebec!

A generation later, Levine thinks Quebecers’ animosity toward Richler has diminished. “Young francophones now see that he was violently anti-separatist but absolutely pro-French,” he said. “Mordecai simply called people to task for what they did.”

As for his literary legacy, Levine noted that, “Margaret Atwood spent 20 years in the wilderness. Now all of a sudden she is the most famous Canadian writer. My belief is that the quality of Mordecai’s work is so good and his message is so important that his moment will come.”

READ: MORDECAI RICHLER: PRIZED AUTHOR WHO DIDN’T CARE WHO HE OFFENDED

Along with Richler’s family, Levine is trying to develop a number of television and film projects, which he thinks could spark a widespread revival of interest in the author. But he said that it’s not an easy industry to get a foothold in these days.

Levine was joined by Richler’s wife, Florence, daughter Emma and, by video, his son, Jacob. The children, who became emotional reminiscing about their father, concurred that their mother was Richler’s first reader and confidante.

Emma Richler, a novelist living in London, said she could not find a biography of her father in the University of Toronto’s Hart House Library during a recent visit there.

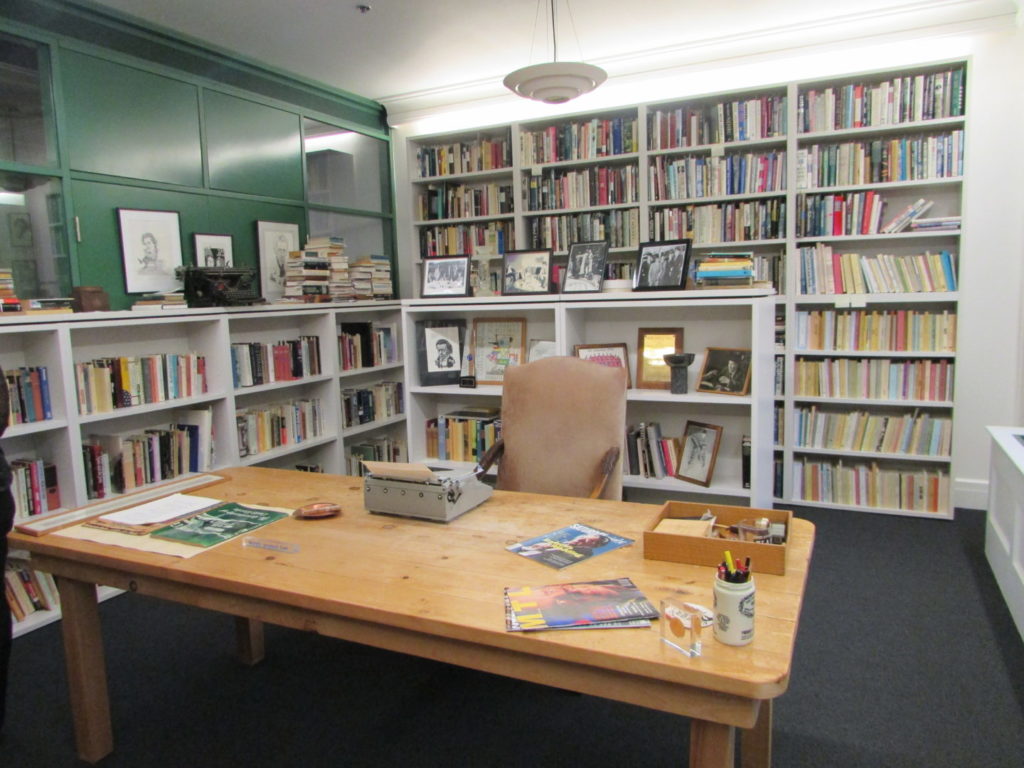

In 2013, the family donated Richler’s personal library – including books, as well as furniture, a manual typewriter and memorabilia – to Concordia. His study at the family’s Eastern Townships country home was recreated in one of the two rooms housing the collection on the sixth floor of the McConnell Building.

Librarians and graduate students have catalogued the collection, which came in 157 large boxes, and a searchable database and virtual gallery are now available online.

A national group of scholars is determining the significance of the items in the collection, supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grant. (Richler’s archives are at the University of Calgary.)

The Richler Library is not intended as a museum. It is used in various ways by students, faculty and researchers.

Katherine McLeod includes Richler’s last novel, Barney’s Version, in the course she teaches on comedy in Canadian literature. But incorporating the Richler Library into her classes is what excites her, even when his books are not on the reading list.

Being in the midst of the author’s working environment is stimulating the imaginations of her young students, who regard Richler, and even print culture, as distant, she said.

The Boréal series is actually a re-translation, because earlier translations done in France were thought to need improvement and a Canadian hand.

Paul Gagné, who translated the books with his wife Lori Saint-Martin, couldn’t say how well they have sold in Quebec, but Solomon Gursky was a bestseller in France when it came out in 2015.

Concordia French studies Prof. Sherry Simon believes Quebecers have “a great affection” for Richler, although Gagné is not so sure about that.

“Richler said bad things about everybody, but his intervention in Quebec politics in the early 1990s, even if he was right on some things, was not helpful at all,” said Simon.

Emma Richler observed that her father’s anger was directed at “small-mindedness. When a language is being policed, it’s a very dangerous thing. Any echo of proscription raised all kinds of spectres for him. Nationalism is a great evil. If there were restrictions on people’s thinking and speaking, he was going to show his porcupine quills.”

The conference, which was public and free, was sparsely attended, save for an evening lecture by Adam Gopnik, a writer for The New Yorker and a longtime friend of the Richler’s.

Gopnik contended that Richler should not be restrictively categorized among the Jewish-American novelists of his generation because his stylistic range is comparable to the storytelling of V.S. Naipaul, classic British satirists and even South American magical realists.