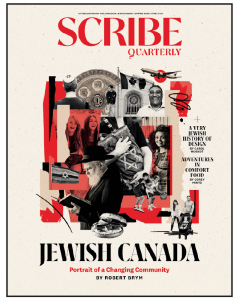

First of a two-part series on Community Advocacy

It’s been two years since Canada’s mainstream Jewish advocacy groups were amalgamated under the umbrella of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA).

As part of that process, venerable institutions such as the 90-year-old Canadian Jewish Congress and the Canada-Israel Committee (CIC) – which had both been effectively controlled by CIJA’s predecessor organization since 2004 – disappeared as independent entities.

The Quebec-Israel Committee, National Jewish Campus Life (Hillel’s parent organization) and the University Outreach Committee were some of the other groups that were absorbed by CIJA.

The aim of the changes, as stated by community leaders in 2011, was to save money and streamline pro-Israel and Jewish activities by speaking with one voice on both domestic and foreign affairs.

But is the Jewish community better off now than it was before?

Proponents of the changes pointed to a need to reduce overlap among existing groups and to “clarify and unify” Jewish advocacy here and abroad.

Shimon Fogel, CIJA’s CEO, told The CJN at the time that “the lines and distinctions between what they used to call ‘the domestic agenda’ and ‘the Israel agenda’ have blurred so much that it’s impossible really to tell one from the other. When is it anti-Zionism? When is it antisemitism? This is the nature of where things have gone internationally.”

Fogel said these distinctions had become “increasingly artificial,” to the point where it became difficult for Congress and CIC to determine which agency should respond to what issues.

“We had an opportunity to integrate and consolidate all the thematic agendas – campus, antisemitism, Israel relations, social policy agenda at the local community level – all of those things could be brought into one holistic institution,” he said.

Critics, however, said the changes were made undemocratically at the behest of large donors who wanted a greater say in how the community responded to a perceived increase in delegitimization efforts against Israel.

Many also bemoaned the loss of longstanding and highly respected agencies, particularly Canadian Jewish Congress, whose leadership was elected from among member groups from across Canada through regular regional and national plenaries.

The critics say the new CIJA structure doesn’t employ the same democratic process and note that CIJA’s board is appointed, not elected.

Sally Zerker, a professor emeritus at York University, is still angry about the way Congress was dismantled.

“It was a totally undemocratic process. Congress wasn’t shelved – it was destroyed. There was no foundation for the decisions [that CIJA] made. The problem for CIJA, as far as I’m concerned, is that they don’t represent the Canadian Jewish community,” Zerker said.

“CIJA has no basis to exist other than for some connected men getting together and making a decision,” she added.

“I have no objection to any group of people organizing any kind of organization and supporting it themselves. However, these organizers of CIJA speak as if they’re representing the community, but they don’t. There was a time, not long ago, when we used to vote for the head of Congress and its directors. That has gone by the wayside.”

Other critics, mostly on the left, argue that some pro-Israel voices are being excluded in the new environment.

Mira Sucharov, an associate professor of political science at Carleton University in Ottawa and a progressive Zionist, said CIJA has presided over a “narrowing in the type of dialogue” about Israel that is restricted to what the organization deems to be appropriate.

“My vantage point is college campuses, and there I see a disturbing attempt to police the kind of discussion that Jewish students may engage in within the auspices of their Hillel organizations,” she told The CJN.

For example, Sucharov said Jewish students at Carleton were discouraged from meeting with Peter Beinart, a controversial Jewish journalist and academic from the United States who favours a boycott of products made in the West Bank and is a harsh critic of Israel’s policies towards the Palestinians.

“A prime example of this was CIJA’s official ‘recommendation’ to Hillel organizations to refuse to engage with Beinart –who is undoubtedly one of the most prominent North American voices of his generation regarding contemporary Zionism and U.S.-Israel relations – when he came on a three-city tour of Canada last fall,” Sucharov said.

“The organizers of his trip – the New Israel Fund, Ameinu [a progressive Zionist group] and Canadian Friends of Peace Now – approached Hillel organizations to see if the students would like to meet with Beinart, and they were told no.”

Sucharov also believes CIJA has shifted the Jewish community’s official advocacy position to the right on the political spectrum.

“CIJA’s actions have made groups like the ones I mentioned above experience their form of ‘pro-Israel’ advocacy as outside the tent of official Canadian Jewish organizing,” she said. “And this, I think, is very unfortunate for the health and vigour of the Canadian Jewish community as it relates to Canada-Israel and Diaspora-Israel relations.”

CIJA spokesperson Steve McDonald categorically denied that his organization instructed Hillel to stay away from Beinart. “We don’t tell Hillels what to do. Hillels work out their advocacy programming locally in concert with their federation. We provide national support, particularly in the form of training, resources, and advice,” he said.

McDonald added that tour organizers asked multiple Hillels if they wanted to host Beinart, shortly after he wrote an article in the New York Times advancing his boycott argument. “Those Hillels in turn asked us for advice, to which we shared our own policy and encouraged Jewish communal organizations to adopt a similar policy. Our position that we don’t provide a platform for [advocates of boycotts, divestments and sanctions against Israel] – i.e., sponsor or host, and in turn use our communal resources to promote – is utterly different from ‘don’t speak to or engage with.’”

Harold Waller, a political science professor at McGill University and a longtime observer of Canada’s Jewish communal structures, says CIJA’s impact has been both positive and negative.

“There are undoubtedly some members of the community who believe that the present arrangement imposes excessive community discipline… [but] on the positive side, the community purportedly speaks with one voice to other Canadians and even those beyond Canada’s shores,” said Waller, who sits on the Canadian Institute for Jewish Research’s academic council.

“Presumably this enables us to husband our resources and deploy them in a more cost-effective way.”

Another benefit to the CIJA-led advocacy structure has been “the opportunity for a more rational allocation of resources devoted to advocacy and… presumably clearer statements of community positions,” Waller said.

As well, CIJA now has access to more federation resources and funds from “private benefactors,” he said.

But, Waller added, there’s been criticism about CIJA’s perceived lack of democratic accountability, as well as its “presumptions regarding being the main spokesperson” for the Jewish community.

Furthermore, there’s been a lack of “any forum or mechanism [within CIJA] to work out disparate points of view on the issues that we must address.”

In addition, Waller highlighted the lingering resentment among some community members who believe Congress was abandoned too easily.

“The advantage of Congress was that it represented a wide range of Jewish organizations, so it could speak authoritatively. CIJA basically comes from the federation movement. It can also claim to have wide backing from all the individuals who donate to their local [federation] campaigns, but that kind of representation is far different from what Congress claimed to have.”

CIJA could also do a better job in making itself known to the community, he said.

“I am sure that people in government and politics know what CIJA is, but I doubt that members of the general public really understand its significance,” Waller said, noting that the Jewish community likely understood how Congress functioned, given its longstanding role.

Still, he believes that most Canadian Jews are “satisfied” with CIJA so far, and that there are fewer dissenters today than in 2011, although they’re still outspoken, particularly those who are passionate about Congress’ legacy.

When asked whether Congress’ absence and CIJA’s ascendance have helped other community advocacy organizations carve out a more prominent role for themselves, Waller said he doesn’t think so.

He said CIJA’s only real rival is B’nai Brith Canada, but in his view, its efforts have been unaffected by CIJA.

“I don’t know of any other Canadian Jewish community organization [aside from B’nai Brith] with a truly national presence that can claim to be an alternative to CIJA,” he said.

Asked whether he thought the Friends of the Simon Wiesenthal Center Canada (FSWC) has had a greater impact as a communal organization since Congress’ demise, Waller said no.

FSWC “appears to be a small-scale operation with a limited range of concerns,” he said.