Quebec high school teachers now have a guide to discussing genocide, thanks to a decade-long effort by the daughter of Holocaust survivors who believes educating students about this complex topic is more critical than ever.

Heidi Berger, who was motivated by what she saw as a profound ignorance among students she spoke to about the Holocaust, is the driving force behind the new pedagogical resource Étudier les genocides.

The guide was produced by the Foundation for Genocide Education, a non-profit organization she created in 2014, and is supported by the Ministry of Education, which is making it available to all high school teachers in Quebec.

Berger found that many educators wanted to teach about genocide but lacked the materials or the confidence to address a subject that is so fraught and overwhelming.

“This is ground-breaking,” said Berger, who regrets that genocide receives “little more than a paragraph” in the mandatory world history text.

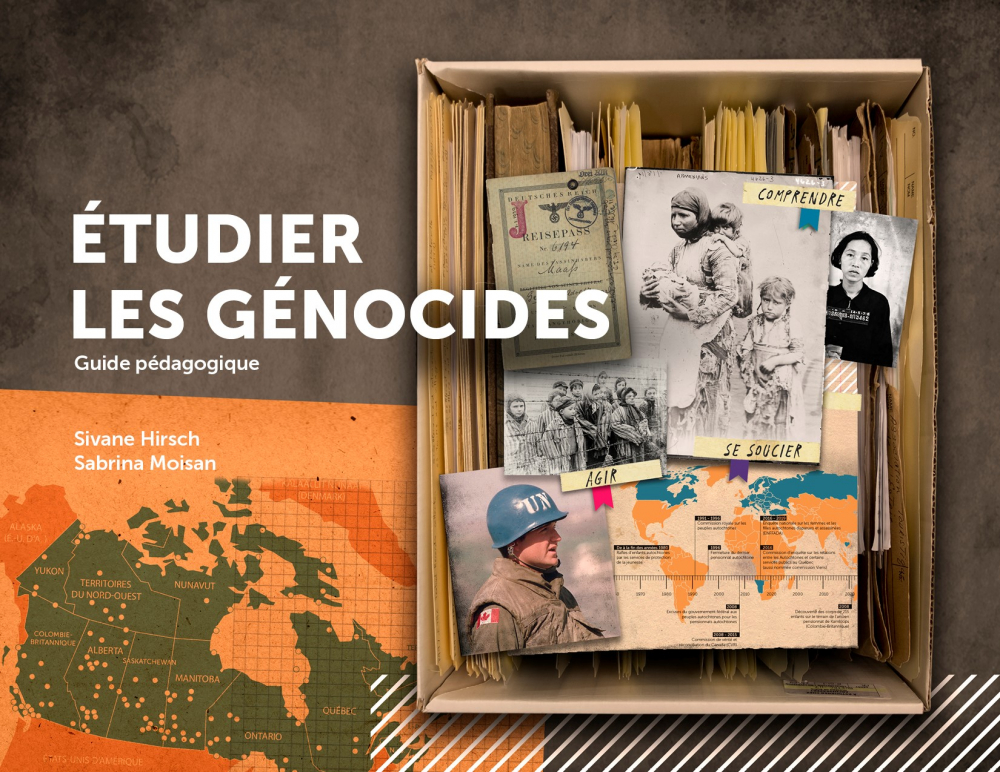

Written by education professors Sabrina Moisan of the Université de Sherbrooke and Sivane Hirsch of the Université du Québec à Trois Rivières, the guide covers nine genocides of the 20th century. They were supported by an inter-disciplinary team of experts and community groups affected by genocide.

Besides the Holocaust, the genocides are those against minorities in Namibia, Cambodia, Rwanda, and Bosnia; the Ukrainian Holodomor, the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, the Nazi murder of the Roma and Sinti, and, perhaps controversially, the Indigenous peoples of Canada.

The guide was launched in April as part of Genocide Remembrance, Condemnation and Prevention Month, which encompasses Yom ha-Shoah.

It is available online to teachers in Quebec’s 800 high schools, who reach over 343,000 students. An English version is forthcoming.

The package also includes teaching plans, reference documentation and instructional videos. Recorded testimonies by survivors or their descendants living in Canada today will also be offered. Teachers can participate in workshops on how to use the guide effectively.

It will be up to teachers how they incorporate genocide. An obvious choice is the contemporary history course senior high school students take, but it might fit into ethics and religious culture (soon to be replaced by a new civics course), or second-language instruction.

“Ignorance often translates into hate, and we believe that an essential part of the solution to end hate begins with education,” said Berger. “We believe that this guide will help students develop critical thinking skills to allow them to recognize the signs of intolerance and racism, and equip them to speak out against hate wherever they encounter it.”

Berger spent years lobbying successive education ministers and meeting with numerous civil servants to persuade them of the need to address genocide. The Foundation for Genocide Education raised funds privately to underwrite the development of appropriate pedagogical materials.

Although she believes genocide education should be mandatory, Berger says no educator should be forced to teach such a fraught and overwhelming subject without the right support. The materials were piloted in a number of schools last year.

“To address as sensitive a topic as genocide in the classroom, teachers need to be well equipped,” said Hirsch, one of the authors. “(The guide) will become a true reference for teachers who may feel uneasy about the subject or the right ways to educate students about these tragedies, their causes and their impact on the history of the 20th century.”

Berger noted that this is the first pedagogical module addressing the subject of genocide in such a systematic manner in Canada.

“A lot of people told me it couldn’t be done, but I just never took no for an answer,” said Berger, a film producer who has taught at Concordia University. “Any resistance we encountered just made us more resolute in our mission.”

Berger began making presentations on the Holocaust in schools in 2008, following in the footsteps of her late survivor mother Ann Kazimirski who spoke frequently about her experience.

Having grown up in Ste. Agathe in the Laurentians, Berger’s fluency in French allowed her to reach a broader audience. Using her communication and film skills, she toured her one-woman show around the province anywhere the door was open.

The guide offers more than a chronology of historical facts; it focuses on what leads to attempts to annihilate a people, which typically starts with dehumanizing them, Berger said.

“I like that the guide includes an action plan that shows the students how to address discrimination and hate in their own lives,” she said.