He was not a man of letters in a style traditionally bestowed upon great scholars.

Joe Fishstein, who immigrated to New York City from his native Bessarabia (later Moldova) in 1910, was rather a long-toiling sewing machine operator living in the Bronx. He was a union man, a husband, a father and a grandfather.

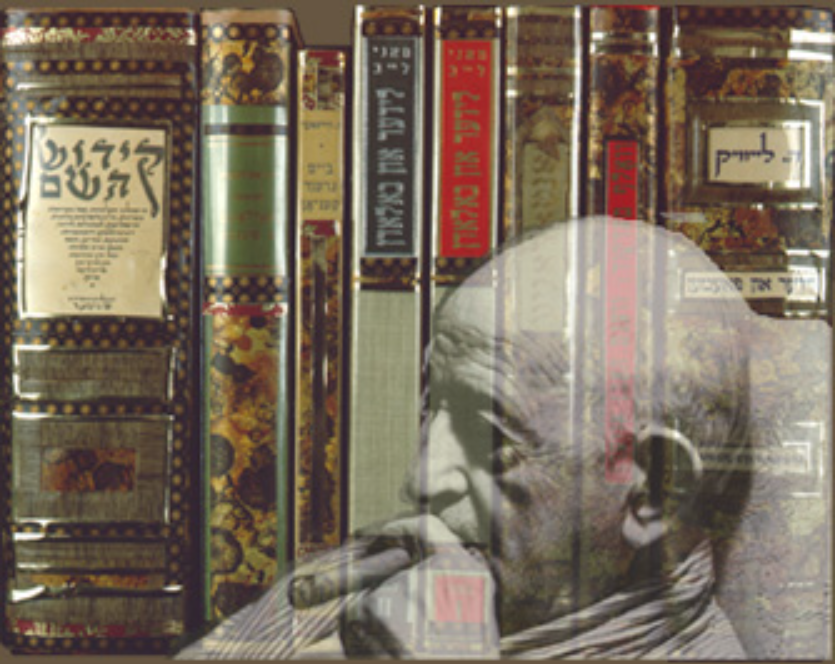

But as a lover of all things Yiddish, especially poetry, his lifelong romance with the mamaloshen and its centrality in European and global Jewish culture manifested in his meticulous collection of some 2,300 volumes that have stood the test of time and endured in hearts and minds of Yiddish speakers and literature lovers worldwide.

Born in 1891, he spent countless hours adorning his collection with beautiful handmade covers and cases that reflect his loving and protective stewardship. Montreal was the chosen benefactor of that careful attention to and passion for Yiddish literature, an indelible gift to the last century that keeps on giving.

Housed in McGill University’s Division of Rare Books and Special Collections at McLennan Library, the Joe Fishstein Collection of Yiddish Poetry is considered one of the finest private collections of its kind in the world. The catalogue was edited and curated by Goldie Sigal, a former Jewish Studies librarian whose 1998 exhibit introduced the collection to the broader community, 17 years after it was gifted by the family to the school.

Liaison librarian Ursula Carmichael says it has served as a treasure trove for researchers, students, and historians:

“Our mission is to support research, teaching, and learning,” she told The CJN, “and a big part of our work involves outreach, using our collections for learning and collaboration with the McGill community, the Montreal community, and beyond.”

As the name implies, it’s mostly poetry, but remarkable for several reasons—including the fact that it contains both rare and standard works of some well-known Yiddish authors like Sholem Aleichem, Itzik Fefer and Miriam Ulinover, along with publications featuring more than 400 illustrations by the great Jewish artists, including Marc Chagall.

While this proud acquisition is eclipsed in size by larger collections in New York City and elsewhere, Sigal wrote in the catalog that “its importance lies chiefly in the fact that it contains a surprising number of works seldom found elsewhere and that most of its volumes have been preserved in vintage condition.”

Something sparkly for tonight’s #Hanukkah gem – a small selection of handmade book jackets crafted by Joe Fishstein, using everyday objects like drawer liners. Learn more about Fishstein from the digital exhibit in his honour: https://t.co/e5gsuSWrsv pic.twitter.com/sp1YJgj05C

— McGill Rare (@McGill_Rare) December 7, 2018

Married with two daughters and five grandchildren, Fishstein was one of thousands of Yiddish-speaking immigrants, some aspiring artists, toiling in sweatshops and other trades. But literacy and culture in the early 20th century was so important to the Jewish immigrant experience that more than 150,000 people reportedly have attended Aleichem’s funeral in 1916—shutting much of New York City’s commerce for the day as the city and workers paid respects to the beloved scribe.

In addition to elaborate covers, he also fabricated bookmarks that he clearly used. “Many of the materials and the items in the collection are in really wonderful condition” said Carmichael, adding that shadow imprints of bookmarks are still visible in some volumes. “It connects us to him, the man who so adored these books and looked after them in so many ways.”

The imprints’ geographical breadth spans the globe, many published in Poland and the U.S.—particularly New York City—but also Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, China, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, South Africa, and Canada. “And all of it housed here at McGill in Montreal, including some books actually published here, which makes this particularly special.”

Chag Sameach to everyone who is #TogetherButApart in celebrating this year's #Passover

— McGill Rare (@McGill_Rare) April 8, 2020

[Image from the Joe Fishstein Collection of Yiddish Poetry: https://t.co/iffYpqqZuc] pic.twitter.com/ltR9wGEEXS

After the death of Fishstein in 1978, former McGill—and current Harvard—professor Ruth Wisse heard about the collection “and was blown away” on her first look, said Carmichael. Indeed, in her preface to the catalogue, Wisse—who facilitated the gift to McGill and was instrumental in establishing its Jewish Studies program some 50 years ago—recorded her first impressions visiting Fishstein’s home in the fall of 1980: “The place was being readied for a move, and most of the furniture was already gone. But around the room, on white bookshelves, stood a library such as I had never seen…”

Even before approaching the shelves, she felt that she had stumbled upon an intellectual goldmine: “Joe Fishstein had wanted his books to look as precious as they felt to him, so that their beauty should be palpable, the way they were in the great leather libraries of yore. He had transformed the modest room into a happy shrine… The sense of sanctity still permeated his home.” He had a standing order with Yiddish bookstores to collect every poetry title published anywhere and spent his Saturdays with what Wisse described “transferred religious awe,” reading, adorning his acquisitions, and copying favourite poems into a private album.

This week, Goldie’s granddaughter Claire Sigal, a historical Judaica embroidery re-creator who lectures on the intersection of textiles and literature, led a McGill workshop monogramming bookmarks in tribute to the collection, which also includes archival and ephemeral items like Fishstein’s wallet, and scrapbooks of articles, trade union memorabilia and other items reflecting his devotion to Yiddish theatre and the cultural life of New York’s early 20th-century Jewish community and wider social history.

Claire says Yiddish poetry continued its traditional romanticism in the diaspora, even while more modern and bittersweet, with “the hardships and also the sweetness of having this unique culture and the immigrant life and family. This still remains in much of Jewish literature to this day,” along with references and allusions to the needle trade in some of the works in the collection, including those of Ukrainian-born Mani Leib (1883-1953).

“So many Jews, when they came to Montreal and New York, they were working as needle workers. Some were allowed in Canada or New York simply because of their sewing skills, how well they could really sew for coming here. Sometimes they faked it, but in the end, we got here, and a lot of the times worked in these sweatshop conditions.”

“Poetry is the best illustration of history” Claire told The CJN after reciting “On the Other Side of the Poem” by Galician-born Rachel Korn (1898-1982), who only learned Yiddish in her 20s and emigrated to Montreal in 1948. “Nobody conveys feeling like a poet.”

To see the enduring interest and admiration for the collection, said Carmichael, “is an absolute joy. Honestly, it feels like a privilege to interact with these materials.” Balancing preservation and access is always a concern as the library aims to ensure items remain in good condition for future generations, while also ensuring that materials of literary, cultural, and historical importance are accessible for people to interact with, to experience the embodied reality of history and culture. “

The collection reflects layers of love, pride, and intellectual energy… through his collecting, decorating, and maintaining works, and his joy in recopying poems, we see a man’s devotion to literature and community.”

Fishstein’s legacy is a treasure that grows in value, says Carmichael, an active member of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union “working long hours under difficult conditions, largely self-taught with a passion for poetry, making his story resonate with many who find joy in reading and creative expression, regardless of background or socio-economic status.”

“It’s really special, because someone who was not of means, with demands on their time, a father, husband, and working in a sweatshop-like environment, carved out this time to spend with these materials and these works.”

Author

Joel has spent his entire adult life scribbling. For two decades, he freelanced for more than a dozen North American and European trade publications, writing on home decor, HR, agriculture, defense technologies and more. Having lived at 14 addresses in and around Greater Montreal, for 17 years he worked as reporter for a local community newspaper, covering the education, political and municipal beats in seven cities and boroughs. He loves to bike, swim, watch NBA and kvetch about politics.

View all posts