It was close, but Toronto synagogues Adath Israel and Beth David will remain separate entities after Beth David’s vote on amalgamation fell short of the required two-thirds threshold.

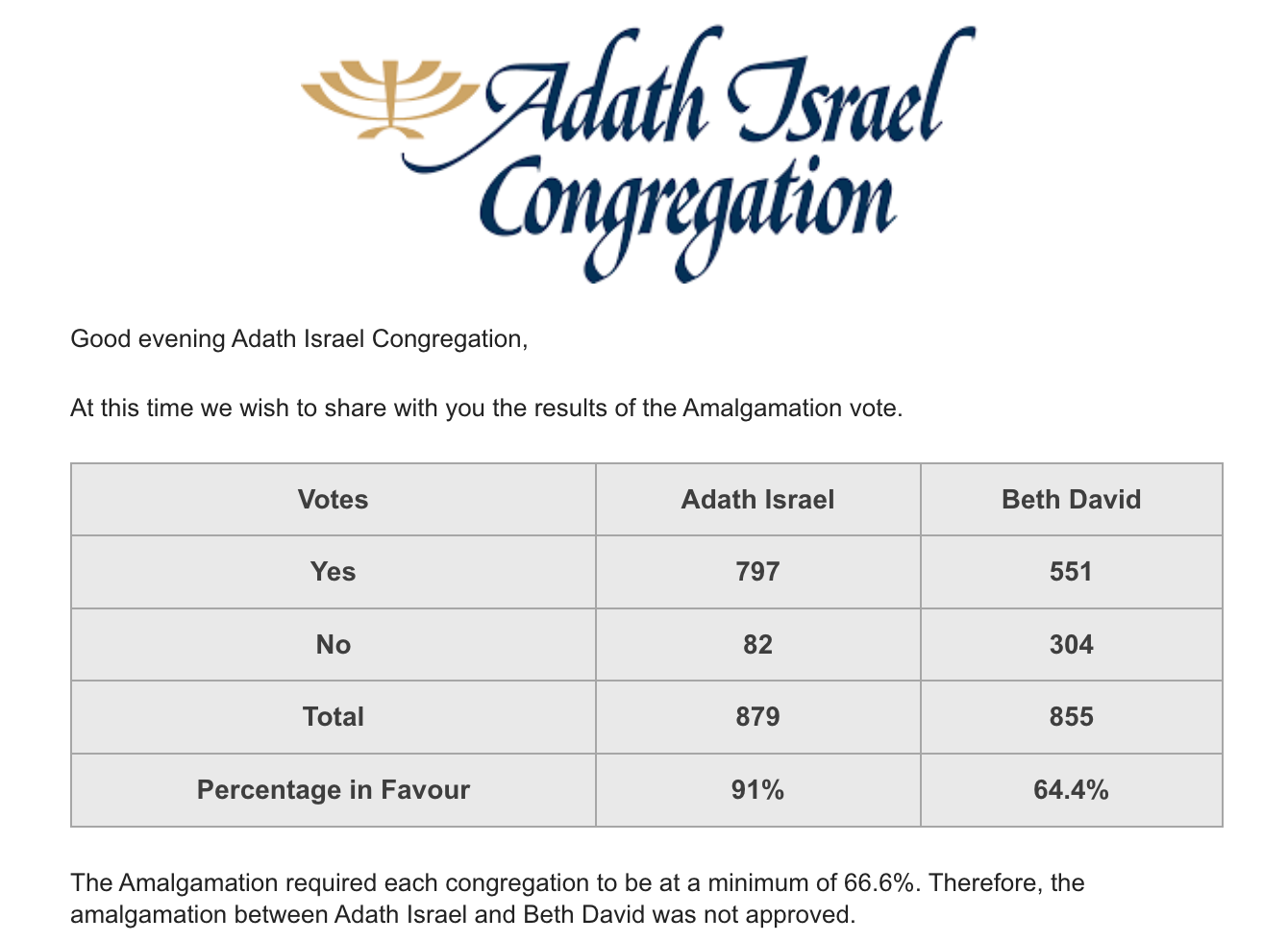

Adath Israel, the larger of the two Conservative synagogues by membership and facility size, voted overwhelmingly on April 14 to amalgamate, with 91 percent in favour. But Beth David’s members reached only 64.4 percent, 2.2 percentage points shy of the 66.6 percent threshold required from both sides for these major changes under Ontario’s Not-for-profit Corporations Act.

Beth David’s president, Silvia Lulka, told The CJN that more than 80 percent of the congregation’s members voted, with 855 casting their votes out of more than 1,000 eligible voting members.

The proposed amalgamation followed years of decreasing membership and increasing costs at Beth David, whose facility is older and requires more maintenance. Following board elections in June 2023, two committees explored both “evolving independently” and an amalgamation with Adath Israel.

The two congregations share a Toronto neighbourhood as well as a Conservative religious affiliation. Adath Israel welcomed the merger’s financial advantages and potential to ensure its future longevity.

Beth David also recognized a need to increase the number of younger members.

Members of both communities were enthusiastic to consolidate congregations, which would have meant sharing clergy, administration, and governance. Beth David would have also moved to Adath Israel’s larger, more modern building.

Lulka says there’s a lot of reflection going on today among members.

“More than 80 percent of people voting tells you that this really mattered to people, to the people who voted… 64 percent of a community is a fairly large number of people in that community,” she said.

“We didn’t quite meet that [two-thirds] threshold, although it’s a very significant number.

“The sense I have from all of [the members who voted] is that they really wanted to look at how we build a new future together.”

She says those who voted to amalgamate “did so because they had a belief in a community that is stronger when combined.”

Of the two synagogues, Beth David’s facility is the smaller and in need of more maintenance, and the amalgamation would have involved moving into Adath Israel’s larger building. Lulka says some people wanted to stay put.

“I think the people who voted no generally had a sense of not wanting to leave the building, and leave how they have to find their community,” she said.

In Toronto, diversity of options has become more of a consideration, says Lulka.

“The reality is that all shuls are going through this. We were built on a different model” from 70 years ago.

“I often used the analogy of coffee to say if you drank coffee in the 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s, you drank coffee or you had Sanka. That was it. You didn’t have choices.

“If you were Jewish in Toronto in the 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, you belonged to a shul… Conservative, Orthodox, Reconstructionist, Reform. If you want coffee today, and 10 years ago, there’s more variety than you and I can make,” she said.

“If you want to be Jewish in Toronto today, you can go to Chabad one day… Darchei Noam (a Toronto Reconstructionist synagogue) another day, and never step foot in the synagogue where you’re required to pay membership. The model has changed. What we need today is different,” in terms of ways to adapt how the synagogue operates.

“I think it’s important for us to regroup and recognize that while it’s not the outcome we had hoped for, because we had endorsed the amalgamation, it’s still a significant number of our members who are supporting,” merging with Adath Israel, she said.

The Beth David community that was thriving, before COVID, used to offer three prayer services a day.

“We had two in the morning and one in the evening. Now… we have one in the morning and that’s it,” she said. “We used to have a thriving Hebrew school. This year we didn’t get enough enrolment.”

Lulka says the demographic shifts in the community have led to fewer members in recent years. Any thriving community, synagogue or not, needs two major elements.

“You need the financial resources to make it happen, and you need the people to make it happen. And on our own, we really don’t have enough of either to fulfil our vision. And so that’s part of what we need to look at now is to say: ‘Where do we go from here? What is the future? What does the future hold for us?’”

Beth David has been running a deficit to keep up with maintenance costs for the older building as revenues from memberships decreased.

The need to “shift the thinking of our model and how we how we operate,” says Lulka, led to two committees forming to explore an amalgamation, or “evolving independently.”

Previous discussions about an amalgamation with Congregation Beth Tikvah, two years ago, were called off when Beth Tikvah decided against it. Subsequent explorations of amalgamation led to the discussions with Adath Israel in 2023, which brought the two congregations to the April vote.

“Every idea that was brought forward was explored,” in Beth David’s committees, Lulka said. “Now we need to regroup and see where we go.”

For his part, Shaul Dwosh, the president of Congregation Adath Israel, says he’s disappointed, but grateful for the amount of work that teams at both synagogues put in.

“I’m not sad. I’m not angry. But people worked hard, and it’s just a sense of disappointment,” he told The CJN in an interview. “In our lives, I guess we learn to experience disappointment, and you can’t always get what you want.”

Dwosh received messages and emails from surprised members, many of whom expected the amalgamation to go through.

While Adath Israel’s current situation is strong, says Dwosh, with 1,400 members and balanced books, the future is uncertain “in terms of demographics.” The congregation largely saw amalgamation as an “opportunity to secure our future.”

“We really thought this was a great thing for the Jewish community as a whole,” he said.

“The amalgamation would have given us the financial resources and the critical mass to kind of ensure long term sustainability.

“There shouldn’t be struggling congregations. There should be vibrant, thriving congregations. And this was a way of creating that.”

While Adath Israel voted 797 Yes to 82 No to amalgamation, it was Beth David’s 551 Yes and 304 No votes that fell short of the threshold. But he understands the factors that went into the vote results.

“Beth David had a much higher hill to climb, in that when you’re at a congregation 60-plus years, to get up and leave your building, your home, takes a lot,” he acknowledges.

“That’s a much, much more difficult proposition. This past Sunday, they weren’t there yet,” he said. “They had 64-plus percent, but it wasn’t what the legislation requires for a decision like that… we respect that, for sure.”

Similar to Beth David, Adath Israel has had to adjust the number of prayer services to ensure a full minyan of 10 Jews.

Since the Hamas attacks on Israel on Oct. 7 and the ensuing war in Gaza, “Jewish connection has become more important… you see that throughout the community. And I think as part of that, I think there’s been just a newfound emphasis on the role of synagogues in the lives of Jews in our community.”

“I’m at the shul every day, so I see it up close each and every day,” said Dwosh. “And it gives me really immense hope.”

He thinks the amalgamation conversations might enter the picture again down the road.

“I don’t think this is the end of shuls amalgamating and merging. I speak regularly with the other presidents of all the Conservative shuls,” he said, mentioning that he and Lulka will be on an upcoming monthly call among congregational leaders where they might be asked to share tips or takeaways from the experience.

“This wasn’t the first talk of mergers, and it won’t be the last talk of mergers, with Conservative shuls in our city, I think, in the next 10 years.”

Author

Jonathan Rothman is a reporter for The CJN based in Toronto, covering municipal politics, arts and culture, and security, among other areas impacting the Jewish community locally and around Canada. He has worked in Canadian online newsrooms and on multimedia creative teams at the CBC, Yahoo Canada, and The Walrus. Jonathan's writing has appeared in Spacing, NOW Toronto (the former weekly), and Exclaim! magazines, and The Globe and Mail. He has also contributed arts, music, and culture stories to CBC Radio, including an audio mini-documentary report from Brazil.

View all posts