Sherry Clodman was relaxing in bed, thinking about how in a few hours she was going out with her family to celebrate her 68th birthday, when the phone rang.

She heard a quiet, quivering, gentle voice and for a moment she thought it was a child calling, until she heard the news that changed her life.

“She said, ‘This is Elaine. I don’t want anything, I don’t want to cause any problems,’” Sherry recalled.

“I am your mother’s child. I was given up for adoption at birth through a Jewish adoption agency.

“In May 1942, your mother had a baby girl, and I’m that baby.”

With a shaking hand, Sherry wrote down the woman’s name, Elaine Chelin, and they agreed to meet for lunch in a few days, since they both lived in Toronto. Sherry called her sister Debbie Edberg, who was equally shocked. “Not mummy,” she said. “Not our mummy.”

Their mother, Ann Rodney, had died two decades earlier and she had never told them she had given birth to other children.

That call came three years ago. Last year, a fourth sister, Carol Greenglass, the oldest of all of them, was discovered. She had also been adopted at birth through a Jewish agency.

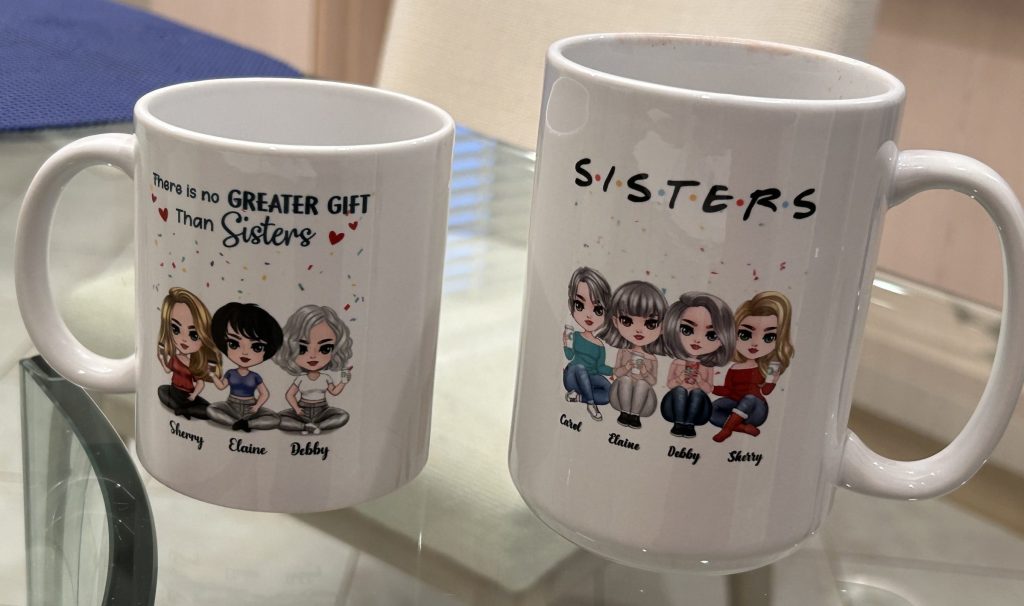

The four women, who all live just kilometres from each other in Toronto, are now between 71 and 85 years old and are rejoicing in their newfound kinship. At a time of life when social circles shrink, theirs has exploded, with newly found nieces, great-nephews and sisters. As Sherry said, “Even now when I say I’m having lunch with my sisters… it still gives me goosebumps.”

But their story is also one about a time of secrets, lies and shame. For decades, the details of the two adopted women were shrouded in sealed records and a heavy cloak of silence. In the end, it was their own courage, some sleuthing and modern technology that united them.

When the four women gather in Elaine’s home to meet with a reporter, they are comfortable with each other, joking about who makes a good brisket and who doesn’t and the differences between widows and widowers. They good-naturedly interrupt each other to disagree on details.

The two youngest are Sherry Clodman, 71, and her sister Debby Edberg, 73, who grew up together, with their mother. Then there are Elaine Chelin, 82, and Carol Greenglass, 85, the half-sisters who are the newcomers to the group. Elaine and Carol, both petite brunettes, take after their mother, Sherry suggests.

In yet another strange twist of fate, Elaine and Carol knew each other for years—they went to the same summer camp as children and belonged to the same golf club and even worked in the same real-estate office as adults. They were friends, long before they learned they were also sisters.

Elaine was the first to uncover some of her family’s secrets. She was an only child, adopted at birth. She had been told that her parents had been married and that her father had died in the Second World War and her mother had decided to place her with a family for a better life. None of it was true.

“In those days it was a shandeh. It’s not like today where people choose to have kids when they’re single because they don’t want to get married or never found anybody to marry,” said Elaine.

Many years ago, Elaine found her own adoption papers, and hired a lawyer to locate her birth mother. Elaine first confirmed with a parent finding agency that Ann was open to meeting her and they met once, in a public park. But Elaine was worried about disrupting her birth mother’s life, who was now married with two young daughters.

She was also concerned about being disrespectful to her adoptive parents. She never arranged to meet Ann again.

When Ann died, Elaine read the obituary in the newspaper and learned her sisters’ names, which were listed along with their husbands and children. Now that everyone was grown, she yearned to connect with them, but she still hesitated.

One Mother’s Day, she went to the cemetery where Ann was buried, arriving at 8 a.m. when it opened. She waited for hours near the grave, thinking that the two daughters would visit that day. She saw Debby, who was at the gravesite, but she had to leave before she would see Sherry. Debby recalls seeing someone near the grave that day as well.

The cemetery, of all places, was not where Elaine intended to meet her new sisters, she said, when they ask why she didn’t come and introduce herself then.

What finally changed Elaine’s mind was a result from 23andMe, the DNA-testing service that recently filed for bankruptcy. Her grandson had taken it, as had Sherry’s son. Sherry had posted on the company website that she would be open to meeting any half-siblings related to her father. Her father, who had been married previously before his marriage to Ann, had been stationed in England during the war and for a few years afterward. Sherry and Debby idly wondered if any children had resulted from that long stay. In fact, no children of their father’s have ever been discovered.

But Elaine read the message and was encouraged. Sherry seemed open to the idea of new siblings. Elaine had her daughter-in-law post an anonymous question on social media about whether she should approach Sherry (the answer was an inconclusive 50-50 split).

“The main thing was I didn’t want to do anything that harmed your mother’s image,” Elaine explained.

Finally, she made that fateful call and a few days later met Sherry and then Debby.

Not long after, one of Carol Greenglass’ granddaughters took the DNA test and turned up as possible match, but the families never connected. It wasn’t until Carol herself took the test—it had been given to her as a gift by a grandchild and she was reluctant to just throw it out—that the fourth sister was found.

When Elaine called Carol to tell her that the two of them had matched as having the same mother, Carol was shocked. She also learned that there were two more sisters in the wings, waiting to meet her.

“I’m not normally a person who’s quiet… I’ll tell you I’m not a person who’s at a loss for words. When Elaine said I think we must be sisters, I was dumbfounded. How is that possible?” Carol recalled.

“You (Elaine) told me in that first conversation that somebody at camp asked if we were related because they thought there was a resemblance and of course, you poo-pooed it, because like, ha ha, how could it possibly be?” Carol said.

“It was a lot to absorb at first. It took me a while to process it.”

Carol was also an only child, adopted at two weeks old, which is the day she celebrates as her birthday. She was 12 when she learned she was adopted and was told her father had been killed in the war and her mother had died in childbirth, or not long after. It never would have occurred to her to search for her birth family, given what she had been told as a child, she said.

Her father died when she was 10, and today she says she has reasons to believe he was also her birth father and had arranged the adoption so he could raise her.

There is only a confusing paper trail, which leads to dead ends. Carol’s late husband, a trial lawyer, had a connection in the courthouse who looked up her birth records, but the names had no connection to what she now knows. More than 80 years have passed since she was adopted. The Jewish adoption agency wouldn’t reveal if it even had a record of her father’s name.

Elaine has also had no luck learning her father’s identity. “Sealed is sealed,” she said, describing her attempts to find records about her birth father.

Sherry and Debby describe Ann as a person with “a heart of gold,” who was outgoing, loved people and was a fabulous cook. She had a great sense of fashion and worked in a few dress stores.

They knew she had been married before, but her marriage to their father was a long and happy one.

Sherry says her mother was the “modern one” who wasn’t afraid to call out right from wrong. “Our friends wouldn’t talk to their own parents, they would ask if they could talk to my mother.”

She thinks her mother would be elated to know her four daughters have finally met each other.

“She would be kvelling.”

Elaine isn’t so sure. “I think she would have been embarrassed,” she said. “She said she wasn’t going to tell you.”

Despite Elaine’s fears, the discovery of two older sisters hasn’t changed Debby’s view of her mother, at all, she says. Rather, it has enriched all of their lives.

“It was meant that we all find each other, it’s karma.”

The four women have started introducing their own, grown children to their new relatives. “My kids think it’s fantastic,” said Carol. “I thought my family was getting bigger when I had two great-grandchildren,” she said. “It’s mindboggling.”

All of them are keenly aware that it could have turned out differently. “Be careful what you look for,” said Elaine. She remembers coming home, after meeting Sherry and Debby for the first time, and telling her son how nice they were -and how relieved she was.

Sherry calls it the best surprise of her life. “These two people,” she said about her newfound sisters, “are, next to my child, the best gift I ever received. And better to have it late, than not have it at all.”

For @People I wrote about my mom finding three half-sisters later in life, including someone she'd known since she was a little girl.https://t.co/f23737KIXC

— Pamela Chelin (@PamelaChelin) February 22, 2025