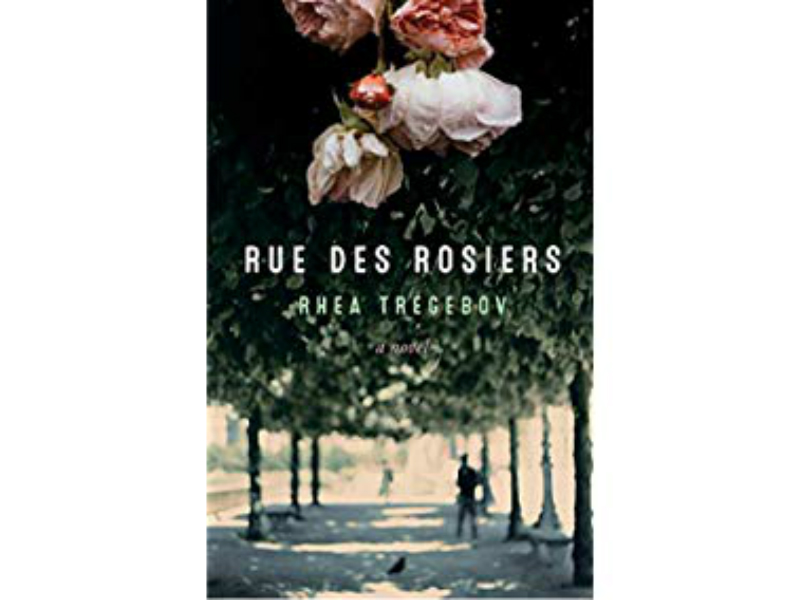

Paris’ Rue des Rosiers is in the news of late, but for reasons more benign than its purpose at the heart of Rhea Tregebov’s new novel, which bears its name. Like the rest of the Marais, a Jewish hub since the medieval period, Rue des Rosiers is under pressure by a familiar global phenomenon: gentrification. Increasingly, it is too expensive for anyone other than an international chain to afford to do business on its tourist-clogged blocks.

In Tregebov’s novel, Rue des Rosiers is the site of a terrorist attack that took place at Goldenberg’s Deli in 1982, which left six dead, many injured, and presented a template to be copied by the perpetrators of more recent massacres of Jews or political targets, such as the cartoonists of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo.

Rue des Rosiers opens before the 1982 attack, and, in shadowy ways, its readers can guess from the beginning that a disaster looms over the novel’s main characters. But Tregebov does an impressive job of moving backwards in time to place her main character, a young Torontonian called Sarah, at unknowing remove from events that lurk, unseen in her future.

Toronto readers in particular will appreciate Tregebov’s rendering of the city in its early 80s guise, from the point of view of women’s activist groups on Queen Street, to the experience of spartan rented rooms on a down-at-the-heels Palmerston Boulevard.

We meet Sarah at a low point. She has a knack for landscape design but works at a garden centre where dedication is not necessarily rewarded. Her relationship to Michael, a young lawyer, is similarly tentative. For reasons she can’t quite explain to herself, she prefers to abandon her partner asleep in his bed to walk the nighttime Annex streets to reach her own bed on Palmerston.

The sudden loss of her job and the coincidence of Michael’s firm’s needs in Paris allow them to break with routine. The book shifts from its Canadian to its Parisian setting.

The latter half of Rue des Rosiers contains a wholehearted literary love letter to the French city.

Sarah is the proverbial free woman in Paris, “unfettered and alive,” as the Joni Mitchell song has it. All the limitations and frustrations of her Toronto existence fall away as she has the opportunity to explore and make the most of her time abroad. A garden specialist tours her through the Luxembourg Gardens, where she takes the measure not only of the park’s design but studies the customs of Parisian leisure.

On her own, she seeks out the architectural treasures of the city, a pursuit which allow Tregebov, via Sarah’s inquisitive gaze, to present carefully detailed descriptions: “Place des Vosges. The heart of the heart of Paris. So much light. The square is big, much bigger than she remembered it. It’s early Saturday morning, so in the strict geometry of the place with its circles and squares, its precision gardening, there’s almost no one. The square is a perfect square, a model of symmetry, the same arcade running along all four sides, paths in perfect diagonals across the inner square. Lines drawn to let people in, not just keep them out. A space that can belong, at least temporarily, to anyone passing through: cleaning ladies, maids, the men in their bright green uniforms sweeping the streets with their sad brooms.”

Sarah’s freewheeling outings are interrupted by her recognition, one morning, of a new graffiti over a subway passage: “The words stop her. . . . Mort aux juifs. Then the English comes to her: Death to the Jews.”

Though Sarah does not witness the act of their writing, the reader does. And so too does Laila, a young newcomer from the Middle East who becomes a kind of secret sharer to Sarah. Through Laila, Tregebov offers another view of Paris. It’s through her that we recognize the city’s cultural and economic divides, as well as the ways in which North Africans and Arabs have changed the city’s character.

READ: PARISIAN BOMBING THE CLIMACTIC TIPPING POINT OF NOVEL

Tregebov’s first novel, The Knife Sharpener’s Bell, linked Winnipeggers with Ukraine. In Rue des Rosiers her past work as a poet contributes to the evocative rendering of charmingly mundane Toronto streets in contrast with Paris’ touristic sheen.

Rue des Rosiers moves expertly toward a dark denouement, but Tregebov leaves room for a kind of rapprochement between her two very different female characters.