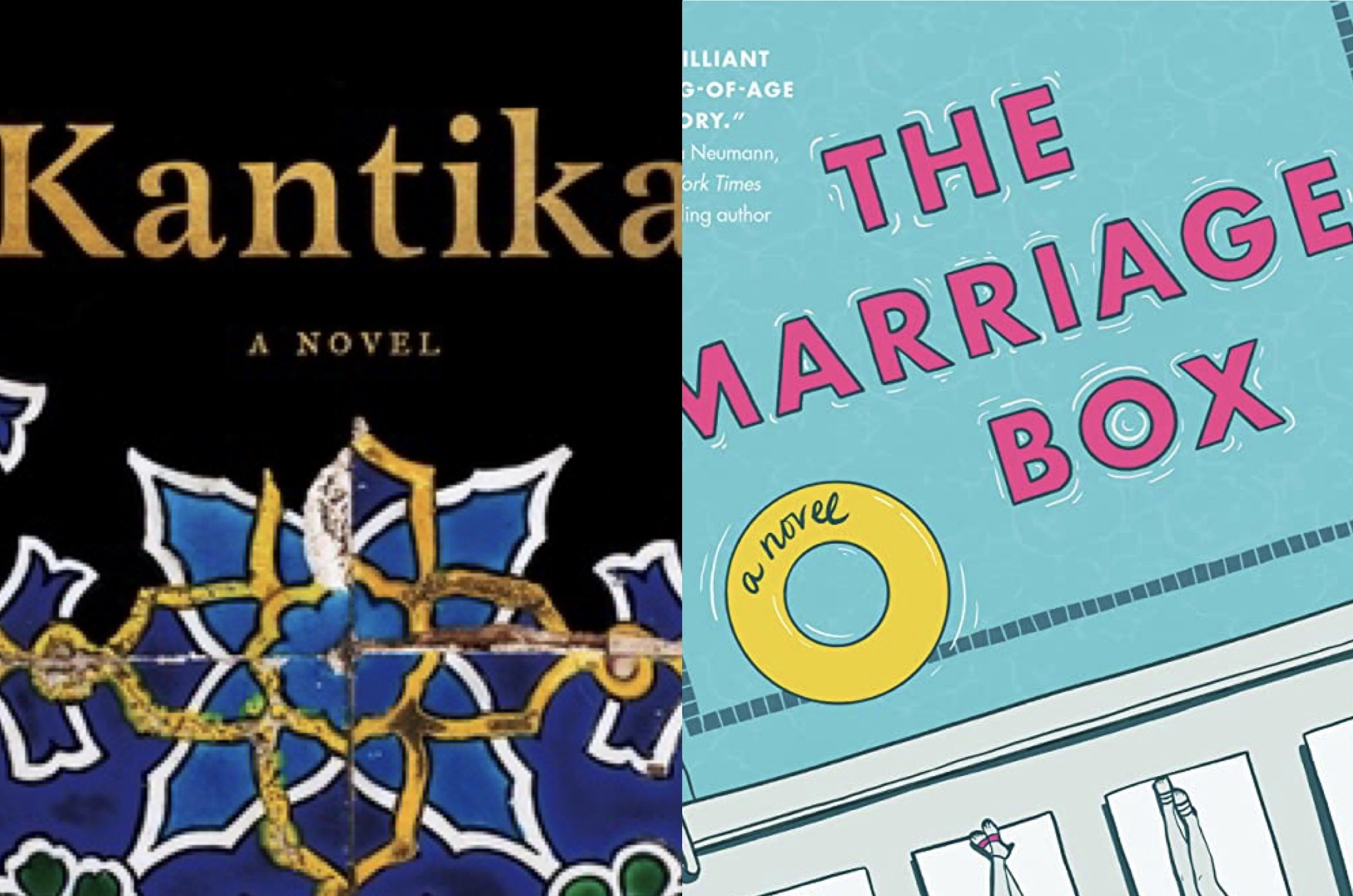

Kantika

Elizabeth Graver

(Metropolitan Books)

The Marriage Box

Corie Adjmi

(She Works Press)

When I think about the English-language Jewish literary landscape, I also notice what’s missing: the stories of Sephardi Jews.

Few people are aware that the very first Jews to come to North America were of Western Sephardic background. And yet, despite a centuries-long presence, there has been a notable absence of a Sephardic literary tradition.

Enter two recently released groundbreaking novels: Elizabeth Graver’s Kantika and Corie Adjmi’s The Marriage Box. Set in different segments of the Jewish community and in different time periods, these narratives shatter conventions by bringing to the forefront coming-of-age stories of Sephardi women. And, in the process, they have won my heart.

Kantika—meaning ‘song’ in Ladino—traces the life of strong-willed Rebecca Cohen from her childhood in Constantinople at the turn of the century, winding through to her adult years in America. Born into an upper-class Sephardic Jewish family, Rebecca’s childhood is almost charmed. Yet the tides change when her family falls on hard times, forcing them to leave their beloved city for Barcelona.

As the book unfolds, Rebecca’s life is continually upended by the turbulent events of the twentieth century and personal circumstances. Despite displacement, including from her own family, she proves adaptable and resilient.

Graver emulates the experience of flipping through the cherished photo albums of elderly relatives: offering an intimate glimpse into the lives of loved ones at a stage in their lives before we knew them. This photographic quality permeates the novel, which in fact draws inspiration from the life of the author’s own grandmother. In fact, the author includes photographs from the life of the “real Rebecca” at the beginning of each chapter. Through these evocative images, she imaginatively brings to life moments previously frozen in time.

Rebecca’s story raises thought-provoking questions about the enduring nature of cultural inheritances across generations, and the impact of migration and displacement. What emerges is the notion that these experiences merely colour one’s traditions, rather than erode them entirely. Rebecca’s own Sephardic identity—her kantika—may adopt new musical motifs, but the song itself remains unwavering.

Corie Adjmi’s novel takes place some decades later, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Marriage Box delves into the story of Casey Cohen as she teeters on the precipice of adulthood.

Trouble begins when Casey falls in with the wrong crowd in her hometown of New Orleans. In a fit of panic, her parents relocate the family back to Brooklyn, believing that immersing Casey in the world of their Orthodox Syrian-Jewish community will set her on a different course. Suddenly thrust into an unfamiliar environment, Casey finds herself in a tight-knit marriage-minded community, where it’s not uncommon for classmates at her all-female high school to drop out to wed.

Though initially resistant, Casey meets Michael, whom she marries when she is just 18. Torn between her intellectual aspirations, and the restrictions imposed by her husband, Casey is left to grapple with whether pursuing one direction would mean abandoning another.

The Syrian-Jewish community is portrayed in the novel as insular and patriarchal, yet it also exudes a profound sense of warmth and strong communal bonds. Adjmi skillfully walks a literary tightrope, presenting Casey’s story with honesty and authenticity without painting an entirely negative view of the community. The result is a nuanced and poignant novel that illustrates Casey’s journey to find her own voice.

In the novel, the ‘Marriage Box’ is a pool deck, where teenage girls lie around in bathing suits to attract potential husbands. It serves as both a physical location and a symbol representing Casey’s own marriage, characterized by profound loneliness and the stifling of her intellectual growth. Many scenes unfold within the confined space of her apartment, heightening the feeling of entrapment. While one might yearn for Casey to break free from the constraints of her marriage, she knows that leaving her husband could result in being ostracized from a community she has grown to love.

I cannot help but feel a deep personal connection to the stories conveyed in both these novels. As a Sephardi Jew, I have longed for literature which reflects my family background. (Much of my own family is part of the Syrian-Lebanese community—which is depicted in The Marriage Box.)

These publications fill a void in the landscape by skillfully capturing the complex inner lives of Sephardi Jewish women, set against a backdrop of profound love for their communities, but without shying away from difficult topics.

The Sephardi woman has finally entered the literary conversation. I hope she’s here to stay.