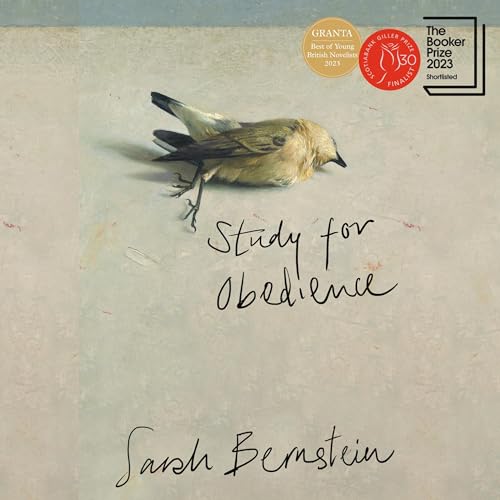

When the prestigious Booker prize announced its 2023 longlist in early August, Montreal-born author Sarah Bernstein’s novel Study for Obedience was among the selected works. The following month, it was revealed as one of the Scotiabank Giller Prize’s 2023 longlist selections.

It was ultimately named the $100,000 winner of the Giller on Nov. 13—Bernstein was then among more than 1,500 writers and publishers who signed an open letter calling for charges against anti-war protesters who interrupted the gala to be dropped—and made it as far as the Booker’s six-book shortlist, losing the top prize to Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song this past week.

This book is being noticed. And though it undoubtedly has universalist appeal, it also carries an undeniable Jewish undercurrent, a fact that has been largely overlooked by reviewers.

Study for Obedience centres around a nameless Jewish female narrator, seemingly raised in a Jewish community resembling Montreal’s. She moves to an unnamed European country, with which she has ancestral ties, to take on the role of caregiver to her recently divorced brother. Among her newfound responsibilities are dressing and bathing him, and managing his daily routines.

As the narrative unfolds, her life is revealed to be characterized by profound ill-treatment. She has sacrificed her individuality in the service of others, a survival instinct developed in her youth when she was made the family scapegoat.

Anticipating that any trouble will be blamed on her (and, somehow, it is), she strives to accommodate others by moulding herself to their needs. As a consequence, she has failed to form any meaningful connections in her life. Fittingly, she has found herself in a career as a legal typist, requiring meticulous attention to other’s voices while keeping her own hidden.

While initially reluctant to engage in town life, as the narrative unfolds she gradually tries—unsuccessfully—to connect with the locals. Despite her professed linguistic skills, she struggles to learn the local language, while also avoiding her native English to avoid appearing rude.

The locals, in turn, remain wary of her, seeing her as an embodiment of Old World superstitions. As strange events unfold in the town—an unexplained pregnancy in a dog, livestock going mad or dying, her brother falling ill—the hostile townsfolk link these to her presence.

The novel’s exploration of the impact of prejudice has universal resonance, but it is the protagonist’s Jewishness that anchors this point, even if the word “Jewish” is never mentioned. This avoidance, treating the word as taboo, mirrors the narrator’s struggle to find her voice. It hints at the fear of acknowledging one’s identity in the face of persecution, and highlights the complexities of being a minority in a hostile environment.

This hostility is reflected in the cold, unyielding natural landscape. Though never explicitly confirmed, at the edge of the town’s forest seems to lie either a mass grave of Jewish victims of the Holocaust, or the remains of a destroyed concentration camp.

The town’s history is conveniently ignored by the locals. The narrator’s presence, as a living manifestation of her ancestors who were not meant to survive, challenges the town’s collective memory and beliefs. This tension intensifies as her brother unquestioningly accepts the local narrative about the Holocaust, one that absolves the town’s non-Jewish residents from having participated in its horrors.

Though a complete peace with her surroundings is elusive, small acts of individuality break through over time as forms of resistance. Toward the end of the novel, following a dramatic confrontation, she seemingly sheds the burden of constant apology and subjugation. This journey raises questions about the true nature of Jewish shame and whether embracing one’s identity can lead to self-acceptance.

It is neither surprising nor undeserved that accolades continue to accumulate for this novel. Study for Obedience is a timely commentary on the complexities of intolerance and of the disenfranchisement of women, and will show the world the talent of the next generation of Canadian writers.

Hannah Srour-Zackon is a contributing book reviewer to The CJN.