There are many reasons to see the production of Man of La Mancha at Ontario’s Stratford Festival this year, not least of which are some that are distinctly “Jewish.”

For example, some scholars suggest that the Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes, was a “Converso.” Indeed, some scholars see in Cervantes’ legacy work, Don Quixote, a coded treatise infused with references to and content from the Kabbalah.

The connection between Don Quixote and Kabbalah, in fact, is the theme of the recently re-released book, Don Quixote: Prophet of Israel, written by French author Dominique Aubier in 1996. In 2009, Nathan Wolski published an article in Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, titled “Don Quixote and Sancho Panza Were Walking on the Way,” in which the author extensively explores “shared themes, motifs and literary strategies” between Quixote and the Zohar, the seminal text of Kabbalah. Cervantes – his life, times and works – has exerted a significant magnetic pull on Jewish scholars. He continues to do so.

But apart from intriguing “Jewish” reasons for seeing this production of Man of La Mancha the many compelling artistic merits of the play warrant the trip to Stratford.

Written by Dale Wasserman, with music by Mitch Leigh and lyrics by Joe Darion, the story of Man of La Mancha is a sophisticated telling of a play within a play that centres on a triple layering of three distinct characters in one person. Played effectively with straightforward elegance and power by Tom Rooney, the writer Miguel de Cervantes is thrown into a dungeon to await trial by the fearsome robed prosecutors of the Inquisition.

Before he is summoned to trial, Cervantes is forced to present his case to his fellow inmates, an unsavoury, unruly and unfriendly group. He does so by devising and performing a drama in which he plays the role of an aging landowner Alonso Quijana. Quijana, however, has an alter ego, the amusing-pathetic, brave-foolish knight errant, Don Quixote de la Mancha. Cervantes’ servant plays Quijana/Quixote’s servant, Sancho Panza. Together, they set about charging after worthy causes. The thugs, cutthroats and miscreants in the jail are given key roles in the play devised by Cervantes.

The lucid-addled Don Quixote is swept off his feet by Aldonza, a rough, forlorn barmaid and harlot whom he sees only as the beautiful and pure-hearted Dulcinea. “A knight without a lady is like a body without a soul,” he tells her. And thus she inspires his chivalry and gallantry.

Robin Hutton is superb in the role of the abused Aldonza. She creates a fiery character that rails with rage and contempt against the prisoners cast by Cervantes as guests at an imaginary inn, always wary of their leering menace. Aldonza seethes with disgust and disappointment at the bitter, hopeless life she leads. Though somewhat uncomfortable with singing notes in the higher register, Hutton effectively conveys her venom and spite toward the men who mistreat her and toward the apparently delusional old man whose frothy, unrealistic myths about her merely compound her misery.

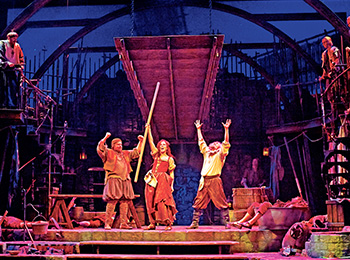

The production is a very physical one. The players seem to be constantly in motion despite the grit and grime of the confined, close quarters of the dungeon they inhabit. Like vermin in a small, tight space on whom harsh light suddenly shines, the prisoners often scurry across the stage in complicated interactions that pointedly convey the mordant, vile conditions of their lives. Marc Kimelman, who choreographed the players’ movements, deserves special commendation.

The shadow of a large windmill dominates the backset. Its huge broken blades, only partially visible, scrape noisily through the wind and the bleak sky. Don Quixote sees in the windmill’s movements the embodiment of an evil enemy. And so, with lance and shield held high, he “tilts” at the windmill, charging inanely at its turning blades, trying to slay a dangerous giant.

When Quijana/Quixote dies, Aldonza/Dulcinea proclaims “that a man is dead.” But his idealism, she implies, is not. The idea is eternal, the man finite.

As if to underscore the message, stars suddenly emerge behind the windmill. The bleak gray sky changes into a sparkling canopy of countless points of light. The import is unmistakable. “The unreachable stars” of Quixote’s credo are somehow less impossible to reach. The blades of the windmill also stop turning. The ogres, villains and monsters of Quixote’s questing mind have been vanquished – at least for him.

As evidence of Don Quixote’s utimate “triumph,” the rough and cynical prisoners – the very antithesis of idealism and honour – take up his theme song, The Impossible Dream. They sing it to Cervantes and his servant as a rallying cry, offering courage and hope to the two men as they are led away to confront the terrors of the Inquisition. Even these human beings cast into the lowest realms of life can be inspired to reach heavenward toward the stars, the playwright suggests. To emphasize the point, Aldonza/Dulcinea becomes the keeper of Cervantes’ work and thus, the custodian of his dream to nourish hope for mankind and the revolutionary belief that human life is sacred.

In this dream, we also hear the echoes of Jewish yearning and faith through the ages.