Estrangement and tension have for decades characterized relations between Hasidic and non-Jewish, mainly French-Canadian, residents of Outremont.

In recent years, that uneasy co-existence has become more strained as the Hasidic communities continue to grow and Québécois become more determined to secularize public life.

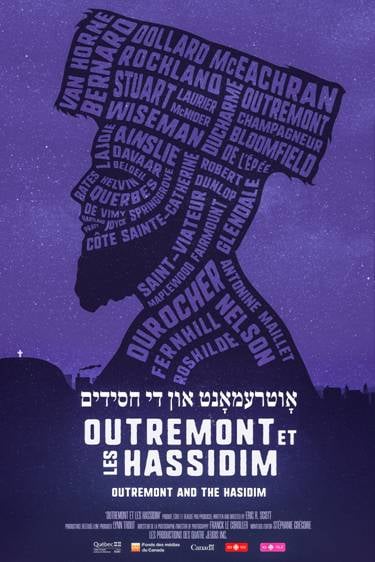

Yet, lately some on both sides have shown a willingness to be more open, especially younger people. That optimism is the theme of Outremont and the Hasidim by Eric Scott, which airs on CBC’s Documentary channel on April 6 and its digital video streaming service Gem for an indefinite period.

The film offers a rare insight into how these very different neighbours view each other. Despite the publicity their clashes have received, neither side has previously been so forthcoming: the Hasidim shun such publicity and francophones, as one older woman puts it, expect to be automatically labeled anti-Semitic.

Divided by culture and language, the interviewees think the other does not like them, nevertheless, they want to know each other better for the sake of a harmonious civic life. First though, they have to overcome awkwardness and lingering suspicion

Outremont, especially its higher elevations, has historically been home to the French-Canadian elite (Premier Francois Legault’s $5-million house is currently on the market). The various Hasidic communities began settling in its more modest sections after the Second World War and today represent close to a quarter of Outremont’s population.

The one-hour film premiered at Théatre Outremont in 2019, an event that itself spoke of a burgeoning rapprochement, and was shown on French-language Radio-Canada, Scott’s production partner, a year ago.

Scott, a veteran independent filmmaker who lives a block outside Outremont, notes that Outremont and the Hasidim, which continues to be streamed by Radio-Canada, is now the third-highest rated Quebec-made documentary on that service. This is testament to the fascination francophone Quebecers have with the Hasidim, which the pandemic has only intensified with the wonder at how – or if – these insular, ultra-religious communities could comply with public health rules.

It took Scott several years to complete the film; finding funding was difficult as was gaining the trust of his subjects. Scott, who is Jewish, is no stranger to the Hasidic world; an earlier film Leaving the Fold looks at young people who left these communities.

Outremont and the Hasidim opens with two longtime sparring partners trading accusations – surprisingly good-naturedly. Pierre Lacerte has long battled what he contends is the Hasidim’s chronic violation of municipal bylaws. Mayer Feig, a feisty, quick-witted community activist, calls Lacerte a liar or at least someone who “twists the facts.”

Exemplifying the newer, more conciliatory generation are two municipal politicians. Mindy Pollak, a Hasidic woman first elected a borough councillor in 2013 at age 24, articulate and personable in English and French, has been an unprecedented bridge-builder. Outremont borough mayor Philipe Tomlinson has struck a very different tone from his predecessors.

The bitter 2016 rezoning battle over a Hasidic community’s bid to open a synagogue on Bernard Avenue, a fashionable commercial artery, contrasts with the visit by the Belzer grand rebbe two years later.

The former episode brought to a boil long simmering feelings. The Hasidim felt they were being denied their basic rights and being driven out, while the many opponents claimed they were concerned with the economic vitality of the street. Lacerte is franker; he saw it as another step toward making Outremont a “larger and larger ghetto.”

By 2018, things had improved, the film suggests. The Hasidic community took the initiative of informing residents in advance of the huge celebrations surrounding the rebbe. That was appreciated, and the Hasidim were pleasantly surprised by Tomlinson’s appearance at the gathering.

“It made us feel human,” says one young man.

Three years on, Scott does not want to leave the impression that everything is just fine. The issue of new shuls is still not resolved, for example. “Synagogues are opening outside Outremont in (the neighbouring borough of) Plateau Mont-Royal. Two opened recently on Park Avenue.”

Some Belzers have relocated much further away, to Cote St. Luc, which is predominantly Jewish. Lower home prices are part of the reason, but not the sole one, he thinks.

“What is happening in Outremont speaks to the broader issue of how Western societies accommodate minorities that are not interested in assimilating. How are we going to make this work?” Scott asks.