Change has been a constant in Warsaw since the outbreak of war in September, 1939. Bombed by the Germans in early attacks, a quarter of the city lay in ruins as the war began. Occupation took its grim toll. In the spring of 1943 the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising led to the razing by fire and artillery of much of the city’s central neighbourhoods; then, the final catastrophe followed the summer uprising in 1944 by Polish underground forces. Defeat after 63 days led to Hitler’s order that the city be leveled, its survivors imprisoned, exiled, murdered.

In 1948, the first major monument to the dead and their efforts at resistance appeared. This was Natan Rapoport’s impressive granite marker honouring the Warsaw Ghetto heroes. The area around the monument – the once-Jewish neighbourhood of Muranów – has been reclaimed by the reviving city. Visiting Warsaw in the decade after the end of communism, one found a large grassy park with Rapoport’s monument at one end, surrounded by a trail of lesser monuments, low-key granite markers inscribed in Yiddish and Polish.

READ: WARSAW-BASED GROUP WORKS TO BRING JEWISH MEMORY BACK TO POLAND

More recently, the park at the junction of Anielewicz and Zamenhofa streets has undergone a sea change. This follows from the public-private partnership between the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland, the City of Warsaw and the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. This partnership, begun in the early ’90s led to the opening of the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews in 2013.

The Muranów park, once a meditative site dominated by Rapoport’s postwar friezes, is now among the major sites of Jewish commemoration, education and tourism in the world.

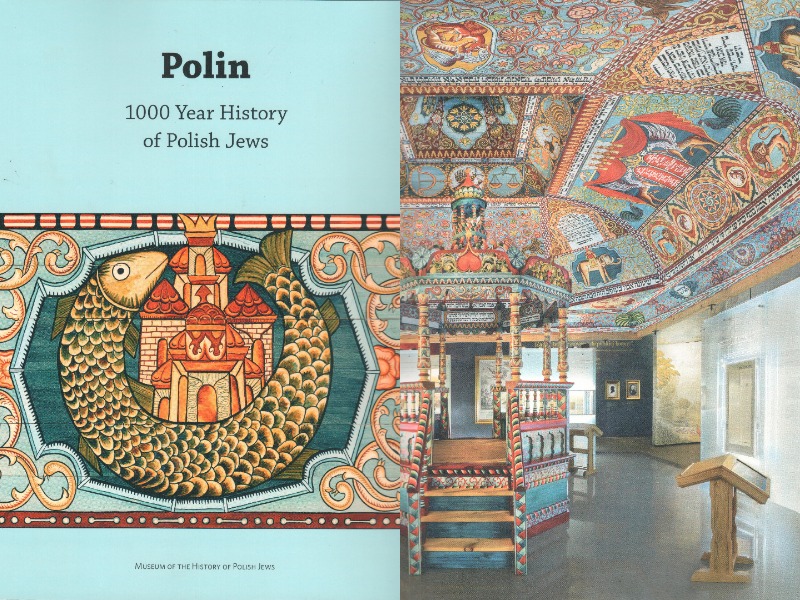

For those who don’t visit, there is an excellent and comprehensive book that captures key aspects of prewar Jewish Warsaw, its destruction by the Germans, and its recent renaissance as both a major European centre oriented toward the west and a site of substantial Jewish commemorative and cultural projects. This is the detailed, lushly illustrated catalogue based on the core exhibit of the Warsaw Polin museum. Called Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews, the catalogue is a ground-breaking text, eminently readable, deeply engaged with the Polish-Jewish past, while making an effort to convey how that past might be relevant to future generations.

The catalogue is a great breath of fresh air in the world of Jewish learning and memory. If enough copies make their way across the ocean, it should join the weighty works that sat on coffee tables in earlier eras, beckoning readers with a comprehensive or crucial tale about Jewish identity and culture.

The Polin catalogue is co-edited by Toronto-born curator and scholar Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and the American historian Antony Polonsky. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett’s introductory essay lays out the museum exhibition’s core principles.

She highlights its historical sweep, from earliest Jewish arrivals in Polish lands in the 10th century; the process of recognition of Jewish rights by royal decree and economic necessity; by the end of the medieval period “the centre of the Ashkenazi world” had shifted from German lands to Poland; while by the mid-1700s the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth was “home to the largest Jewish community in the world and a center of the Jewish world.” Disasters intervened in the course of centuries, leading to the Holocaust.

Included in the Polin catalogue is a curators’ “General Diagram” – a kind of architectural rendering of ideas related to this sweep of history – which plots the range of themes the exhibition and its catalogue aim to address. These include: first settlements, a “Golden Age,” the shtetl or market town, Chassidim, Haskalah, urbanization, der yiddisher gas, Polish-Jewish relations, ghettoization under the Germans and mass murder, followed by the postwar story of Jews in Poland.

With its numerous full-page colour illustrations, Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews conveys the museum’s highlights. Among these are artifacts of early settlement, such as 12th century coins struck in Krakow and Kalisz with Hebrew inscriptions, signalling Jewish involvement in minting. One of the examples of Jewish printing in Poland is a 13th century mahzor, which includes, inserted in its Hebrew letters, what is thought to be the earliest printed Yiddish sentence: “A good day will light up for him who carries this mahzor to the synagogue.”

READ: A SNAPSHOT OF A LOST PREWAR POLISH JEWISH COMMUNITY

A centrepiece of the exhibition and of its catalogue is the reconstructed ceiling, at 85 per cent scale, of the magnificent wooden synagogue at Gwozdiec. Polish and Lithuanian Jews built hundreds of wooden synagogues in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, drawing materials from the Polish forest lands and crafts-people from both non-Jewish and Jewish guilds. Most of these synagogues were burnt to the ground by the Germans, though the Gwozdiec synagogue was lost to fire during World War I. The exhibition catalogue conveys the process of handicraft, artwork and the community of international volunteers that led to its installation.

A major accomplishment of Polin and its associated projects, including the catalogue for its core exhibition, is to remove prewar Jewish Polish culture from the shadow of the German Holocaust and to let it stand, in its varied texture, in its own right. This is an important goal in present post-Holocaust Jewish cultural work. The editors of Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews place themselves at the forefront of these efforts. If one cannot visit Muranów to consider the garden of memorial culture at the corner of Anielewicz and Zamenhofa, a copy of the Polin museum’s catalogue offers a reasonable facsimile of such an adventure.

Norman Ravvin is a writer and teacher in Montreal. He last visited Poland – Warsaw, Torun, Mlawa and Radzanow – in the spring of this year.