Like Deborah Feldman, author of the current bestseller Unorthodox, French author Anouk Markovits also left a Satmar chassidic community as a young woman.

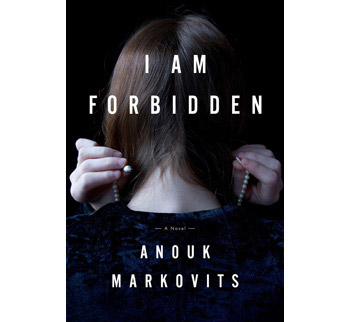

To be published next month, I Am Forbidden (Hogarth), her first English novel, examines the sheltered Satmar community she left behind. But rather than writing a memoir detailing her own experiences or a novel about a woman struggling to leave the community, she instead wrote a novel about a woman devoted to her life in the Satmar community of Williamsburg in Brooklyn.

I Am Forbidden is a respectful examination of the community from within. It spans generations, beginning in World War II Transylvania and ending in present time New York and Paris.

It begins with Zalman Stern, a yeshiva student in Szatmar, Transylvania, the birthplace of Satmar Chassidism. Zalman is an ilui, a wonder of Torah knowledge, and is said to have the most beautiful voice east of Vienna. During World War II, which he survives in Romania, he adopts Mila, an orphaned daughter of his yeshiva friend. She becomes very close with Zalman’s eldest daughter, Atara, who is around the same age.

After the war, Zalman also “rescues” Josef Lichtenstein, an orphaned young boy who survived the Holocaust by hiding with his gentile housekeeper. When he approaches bar mitzvah age, Josef is sent to the Satmar community in Williamsburg.

Zalman also leaves his home, now under the oppressive yoke of communism, and settles with his growing family as a cantor in Paris. He is a pious, deeply religious follower of the Satmar rebbe who escaped Hungary on the infamous Kasztner train (Israel Kasztner made a deal with the Nazis to spirit some Jews to safety at the expense of others) and settled in Williamsburg.

Zalman is unbending in his devotion to Torah and is saddened that even in the Marais, the Jewish quarter of Paris, he can’t find Jews who worship like him. He warns his children to be wary of “Jewish enlightenment” and “modernism” and rails against Zionism. When the girls are caught riding a bicycle in the Luxembourg Gardens on Shabbat, he gives Atara a severe beating while Mila watches in fear.

This is the first time that Atara, who is probably based on the author’s own life, considers rebelling.

Although they attend a Jewish school, Mila and Atara, in their long skirts and thick stockings, are ostracized by teachers and students, especially when they do not participate in celebrations marking Israel’s independence.

While Atara grows more independent and strong-willed, sneaking out to libraries to read “forbidden” books, Mila remains pious and devout. The two are sent to a seminary for girls in England where Mila is thrilled to be among the first generation of chassidic women studying Torah.

But Atara becomes disillusioned. She refuses to accept the school’s teaching that pogroms, and even the Holocaust, were the result of a lack of faith and that a person who fails to connect Jewish tragedies to sin causes further suffering.

Could she marry a chassidic man, one her father chooses, embrace an Orthodox life and raise children who were forbidden to read secular books?

She asks her father if she could leave the seminary and study medicine at a secular university. Her father flatly refuses, and so Atara runs away and Zalman curses her and banishes her from his sight.

Mila also doesn’t return to the seminary as she is of marrying age, and her father accepts a wedding proposal from Josef, now a yeshiva student under the guidance of the Rebbe.

The two settle in Williamsburg and have a seemingly loving relationship. There’s no doubt that unlike her sister, Mila is devoted to her faith, her husband and the Rebbe. She loves the chassidic enclave she lives in, where Jews are not afraid to be Jews.

She wants only to do her duty by giving her husband offspring and enviously watches the other women pushing prams and dragging a train of children behind. Mila dutifully keeps track of her permitted and not-permitted days, but month after month, year after year, she remains childless. (Markovits describes some of the more extreme practices in the chassidic household particularly when it comes to sex and bodily fluids.)

It is customary that after 10 years with no children, the husband can divorce his wife. Mila begs her husband to do a fertility test, thinking he might be the problem, but Josef refuses on the grounds that spilling his seed in vain is forbidden.

The novel races to the present when a secret Mila kept all this time threatens to banish them from the community.

Given that the narrative spans around 80 years, Markovits does a good job of keeping the story tight and concise (the book is just under 300 pages). It makes for a fast and engaging read.

And while there’s no doubt that the author is criticizing not just Chassidism but all rigid fundamentalism, she does it in a respectful and non-aggressive way. The heroine of the novel is, after all, Mila, who remains devout and faithful despite all that’s thrown her way.