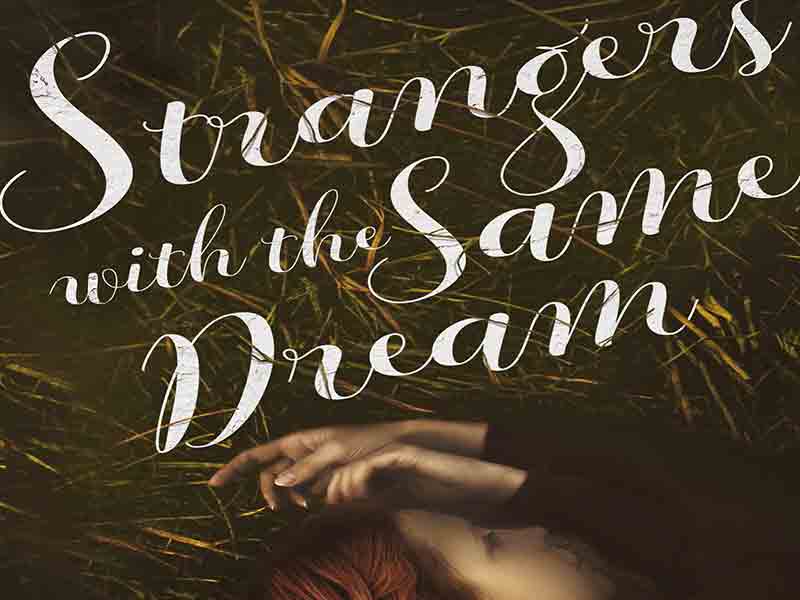

Toronto author Alison Pick, who fictionalized her great-grandparents’ victimization in the Holocaust in her award-winning novel, Far to Go, now turns her literary attention to the redemptive aspect of modern Judaism in her new novel, Strangers with the Same Dream (Penguin Random House Canada).

The book opens with a line of chalutzim, Zionist pioneers, moving across the mountainous landscape near Mount Gilboa and establishing their first armed camp near an Arab village. The first character we meet is an initially anonymous ghost who hovers above the group, providing ironic commentary on all they do. A former Zionist pioneer like the rest, her message, which is repeated endlessly, is that our idealistic acts will have dark and foreboding consequences.

‘Strangers with the Same Dream seems to reflect a level of political insight that has more to do with the present moment than the period it’s supposed to be describing’

Like a habitual wet blanket, the ghost is a seeming know-it-all who likes to second-guess just about everybody in the novel. “Far in the future lies the terrible bloom of what we planted,” she tells as the kibbutzniks are just getting started. “It is your bloom now. The future is a tangle I prefer not to visit.”

Ida, a young pioneer from Russia, feels that she is beginning a new life in this harsh, yet beautiful terrain, and opens herself up to the possibility of love when she shares an intimate moment with one of the group leaders, Levi. But the ghost applies her ironic 20/20 hindsight with the comment: “Later, it was her own blissful ignorance she would grieve for. She didn’t yet know what damage love could wreak.”

Soon the Arabs come out of their houses to gape at the line of chalutzim inching through the valley. David, another Zionist leader, confronts the village mukhtar, and the two face each other “like kings on a chessboard.” Then David raises his hand in greeting: “Salam!” he says, in what must be the most transparent opening gambit ever applied in fiction. “The Hebrew tribe is here to settle this valley.”

Although the kibbutz in the novel is entirely fictional, Pick has indicated that it was based on Ein Harod, the first big kibbutz in the Land of Israel, which was established in 1921. Ari Shavit wrote about Ein Harod extensively in his recent book, My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, a left-leaning book that Pick says deeply influenced her own vision of Israel and the Zionist dream. (She also credits the late American novelist Myer Levin, especially his books Yehuda and The Settlers, for helping her attain local colour.)

READ: JEWISH AND ISRAELI FILMS TO CHECK OUT AT TIFF

Pick is a talented writer and her narrative is infused with realistic descriptions of kibbutz life, overlaid with richly fragrant detail and imagery redolent of the Hebrew Bible. Thus, we get references to threshing floors, donating personal treasures for a superseding common purpose, planting seeds, lapping water from a stream and other familiar tropes, all in a landscape by the biblical Mount Gilboa. In this literary fashion, Pick pays sincere homage to the deep historic link between the Jewish People and the Land of Israel.

Unfortunately, despite their heroic quest, Pick’s pioneers seem mired in the trivial subplots of their daily lives. Ida, for instance, refuses to give up her valuable candlesticks for the collective good and wanders towards the Arab village to find a place to hide them. An Arab woman named Fatima becomes her sympathetic accomplice by offering to hold the candlesticks for her, providing the premise for a series of rising actions that unfortunately become increasingly less credible.

A strong feminist counter-theme runs through the novel, as if to say that Arab and Jewish men may be at each other’s throats, but Arab and Jewish woman can still find common cause. With her strong focus on motherhood and child-raising, Pick offers a neat feminist counterpoint to the prevailing Zionist struggle.

Pick is greatly skilled at breathing life into characters, but even so, in some scenes, her players seem no more than cardboard. And her ghost narrator, who’s always ready to provide ironic comments to the reader on how the characters will feel “later” and “even later,” often seems more of a parrot than a prophet.

Strangers with the Same Dream seems to reflect a level of political insight and consciousness that has more to do with the present moment than with the period it is supposed to be describing.

Political revisionism is the filter through which too many people view events in the Middle East these days. Among the left-leaning crowd, it’s fashionable to cast the Jews as colonizers and Arabs as victims. These attitudes seem embedded in many passages of the novel, such as the following:

“It occurred to Ida that these were the buildings the chalutzim would eventually inhabit if David got his way. But would the Arabs really go as easily as the man in Beirut had promised? This, Ida understood newly, looking at the village, was their home. The Jews needed a homeland, yes, but what right did they have to make the Arabs leave?”

Although written with undeniable artistry, Strangers With the Same Dream seems to offer nothing new or challenging, but it may confirm the prejudices of some readers.

To judge by the many books of the same subject and genre that already exist, the storied hills and valleys of the Holy Land have long been considered sacred terrain for the memoirist, as well as the novelist. Leon Uris’s Exodus is one of the most successful examples and is still famous enough after 60 years to be regarded as a classic. Many others, however, are justly forgotten, picked over even at garage sales, their uninspired plots and political outlook having lagged seriously behind the times and fallen out of the fashion of the moment.