If there were ever a cause for fighting without moral ambiguity, it was the long, hard, horrible fight against the genocidal Nazis and their fascist Axis allies during the Second World War. The passage of nearly 80 years since the start of that war, however, has frosted the glass of time.

When young people today look back on the defeat of the Axis – if they look back at all – they usually see only a hazy outline of the blood, anguish and sacrifice from 1939 to 1945.

The cynical moral relativist quickly points out that the victors – not the vanquished – write our history books. But we do not surrender truth to moral relativists. It is not an overstatement to say that the very continuation of enlightened, progressive, humane Western civilization was at stake in the Second World War.

‘Unabashed and daringly audacious, pack deployed her stunning natural beauty, deep intelligence, crafty resourcefulness and hardened resolve’

And thank God the Allies ultimately prevailed.

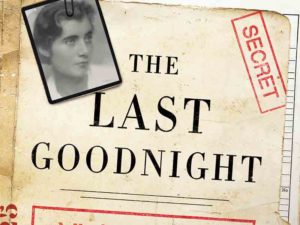

The historic backdrop for The Last Goodnight by Howard Blum is the struggle against the Nazis. The book tells the remarkable story, as the publisher writes, of “a heroine who deserves to be remembered, not only for what she did, but also for all that she sacrificed.” Everyone who fought against the Nazis, of course, deserves to be remembered. The Last Goodnight gives us a rich and rewarding opportunity to learn about, and marvel at, one courageous and uniquely dedicated fighter: Betty Pack.

READ: ON THE OPEN ROAD, FINDING MY WAY BACK TO GOD

Pack was an American who served the British Military Intelligence, the Secret Information Service and the forerunner of the CIA, the Office of Special Services. Her career as a spy actually began during the Spanish Civil War, in which, ironically, her sympathies – at least at the outset of that conflict – were with the fascist Nationalistas.

But there was never any doubt about her loyalty to democracy and freedom. She was a wholehearted soldier on behalf of the Allies, summoning all her strength, will and guile to fight the evil beast that had arisen in Germany.

Pack was a seductress. Unabashed and daringly audacious, she deployed her stunning natural beauty, deep intelligence, crafty resourcefulness and hardened resolve to exact secret information and wartime confidentialities from a wide array of “enemy” one-night stands and lovers.

The nature of her espionage was unquestionably implied in the instructions she received before a key assignment in Washington, D.C., that had vastly significant implications for the course of the unfolding war: “Get close to Lais (an Italian military attaché), get the ciphers and, for king and country, do whatever you must do to accomplish the mission” (emphasis mine).

Pack did not hesitate. In fact, she never hesitated.

Howard Blum.

HARPERCOLLINS

Blum carefully chronicles her exploits in Spain, Poland, Chile and the U.S. He is masterful in doing so. A veteran, award-winning investigative journalist, Blum is acclaimed for the depth of his research. The Last Goodnight is a compelling showcase for his research and writing skills. Blum relied on extensive wartime archives, publicly documented material and Pack’s own notes and diaries. It is a work of non-fiction, but it reads like a mystery thriller, suspenseful and tense throughout.

The book is also, at various times, a historic primer that provides context and reference points for the political or military urgencies that inspired Pack’s various assignments.

For example, of her time in Chile, the author writes: “Betty began, as she would later coyly put it, to snoop a little. Chile was brimming with cells of Nazi sympathizers, a fifth column of bankers, mine owners and landed gentry who brashly schemed with the Abwher (German military intelligence). The government remained officially neutral, but these men were covertly working for the day when Germany could get its hands on Chile’s treasure chest of oil and mineral deposits. They hatched plots galore, many fanciful, but some that sent shivers through the British embassy. It was Betty’s job to infiltrate this nest of renegades and to keep London informed about who they were and what they were up to.”

In a few effective words, Blum pointedly describes the extent of the calamity in Europe: “The dismal month of June 1940 saw a swift series of Allied catastrophes. Holland, Belgium and France had fallen. England was now preparing to make a last stand, rallying its forces and its people for what its new prime minister insisted would be ‘Britain’s finest hour’.”

For the United Kingdom and its people, before the United States entered the war at the end of 1941, the times were desperate and without guarantee of survival. Pack could not remain on the sidelines.

Blum speculates at length about Pack’s complicated, conflicted character. “I do not belong to you or anyone else, not even to myself. I belong only to the service,” she said to someone she loved, betrayed, married, then betrayed again.

“Betty’s talents were unique,” Blum told an interviewer. “She used the double bed as her operational battlefield. She coaxed secrets from the enemy. Her great gift – perhaps any spy’s greatest talent – was to believe whatever she was telling her targets at the moment she was saying it – and then in the next moment to have no compunctions about betraying them. Betty’s only loyalty was to the country and the spymasters she served.”

Blum’s speculations are, at times, a distraction from the raw tension and sheer suspense of the outcomes of Pack’s various escapades. Throughout the espionage narrative, he has woven a psychological assessment of Pack’s personality and motivations for her numerous daring exploits. But these speculations were superfluous to her actual intelligence operations and the far-reaching, positive results they spawned.

One of her spymaster superiors declared that Pack’s achievements “changed the whole course of the war.” He did not exaggerate.