Shabbat shalom,” Anthony Rose says, handing me a yarmulke. “Shabbat shalom,” I reply. I always thought I’d make an excellent Jew – I like books and kvetching and a nice kugel – and the snug way this yarmulke fits just confirms my suspicion.

Anthony’s hosting a Friday night Shabbat dinner for a few friends and family tonight on the verdant little patio behind his Toronto restaurant Fat Pasha. It’s no coincidence that we’ve all gathered here. Fat Pasha is perhaps the most personal of Anthony’s restaurants, the one most closely associated with the foods he grew up eating and, therefore, the one that hits closest to home. It might also be the restaurant he was destined to run.

“Fat Pasha was the first restaurant that came looking for us,” he says. “It was the legendary Indian Rice Factory for over 40 years, so it had a great history, and the owner, Aman Patel, was a fan of ours. He lived nearby, and we were talking one day and he said, ‘You should do something there.’”

Anthony immersed himself in cookbooks to find inspiration. Yotam Ottolenghi was dominating the cookbook shelves at the time – as he still does – with his version of Israeli cooking. The book struck a chord, and Anthony decided this was what the restaurant would be about.

“I forgot one thing, though,” he says. “As a Jew in North America, you don’t grow up with that food. We grew up with Ashkenazic food: latkes, challah, brisket. I mean, I’d made hummus once or twice, but I’d never made a shakshouka, for example. I’d played with some of those ingredients, but didn’t really know them. When I finally realized we could include the Ashkenazic in there, too, it was like the whole thing started to make sense.”

READ: GALA CELEBRATES 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF ICONIC COOKBOOK

Anthony’s mother, Linda, brought her tablecloths and silver candlesticks from home. Food writer Bonnie Stern, a longtime friend of the family, provided the recipe for the challah that plays a central role in tonight’s meal. She has also literally written a book on Friday night dinners, so she brings some pretty serious expertise on the subject to the table.

When everyone is settled with a white Negroni in hand, Anthony gives a little introduction.

“The idea for tonight,” he says, “is that I want to recreate my Sabbath that I grew up with at home with my beautiful mother over here and my gorgeous father. These are her candlesticks and prayer book, and her kiddush cup and the seven-year-old Manischewitz. Mom, you can get us started with whatever it is we do.”

“We drink a lot first,” Linda says, slaying the room.

“No, the first thing we do is light the candles,” she continues. When the candles are lit, she sings a blessing. “Good Shabbas, everyone,” she says when the prayer is over, then announces: “The Rose tradition after the candles is everyone kisses everyone.”

Much double-cheek kissing ensues.

Next, we all take a sip of Manischewitz, my first. “It tastes like Welch’s grape juice,” I say. A common assessment, it turns out. After, Bonnie and her husband, Raymond, break the challah. Then, and this comes as a bit of a surprise, they toss it around the table. “It’s tradition,” someone explains. “You didn’t know? This is a no-holds-barred Shabbas.”

With the formalities out of the way, it’s time to eat.

Sharp plates of pickles arrive along with butter-smooth hummus, bowls of blistered little cherry tomatoes with slices of garlic, smoky chopped eggplant with tahini, muhammara (Syrian chili sauce) with toasted walnut breadcrumbs and matboucha (like an Israeli salsa) with cranberry beans and smoked paprika.

“We don’t eat like this at Shabbas,” one of the guests exclaims.

It’s also my first time trying gefilte fish, and having heard nothing but horror stories about it, I prepare for the worst. Miracle of miracles, it turns out to be delicious. Smooth and smoky and just the right amount of salty.

A plate of crisp, dark little latkes is delivered. “That’s the apex of Jewish cuisine right there,” the lawyer sitting next to me asserts. Anthony’s version, extra-crisp and toasty, makes me think they might just be the apex of all cuisine. Here comes the cauliflower — the whole roasted head all covered in sauces, a steak knife jammed in its top, always turns heads.

Anthony’s now mixing up a bowl of something tasty: caramelized onions and radishes, boiled eggs, crisp chicken skin, and smooth pureed liver. “This is the chopped liver recipe they serve at Sammy’s Roumanian in New York,” he explains, “the greatest restaurant in the world. There’s no better version, so this is the one we serve.” I start out spreading it on challah, but am soon eating it by the spoonful. In fact, like everybody else, I’ve eaten so much that when Anthony announces he’s kiboshing the roasted half chicken and grilled salmon with leek relish he had planned to serve, it comes as something of a relief to the stuffed guests.

This is a common problem at Jewish family events, I gather. Rosh Hashanah, Passover seder, Purim — the results are the same. Everyone fills up so much on the first courses that no one has room for all the mains, of which there are many. Oy vay.

Anthony checks to see if I just want a taste of the salmon or a small piece of chicken.

I demur. “Anthony,” I say, “this dinner, this gathering, everything was geshmak. Mazels.”

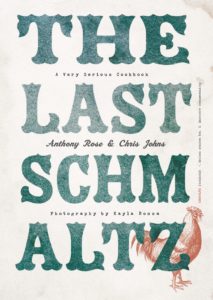

Excerpted from The Last Schmaltz: A Very Serious Cookbook by Anthony Rose and Chris Johns. Copyright © 2018 Anthony Rose and Chris Johns. Photography by Kayla Rocca. Published by Appetite by Random House®, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.