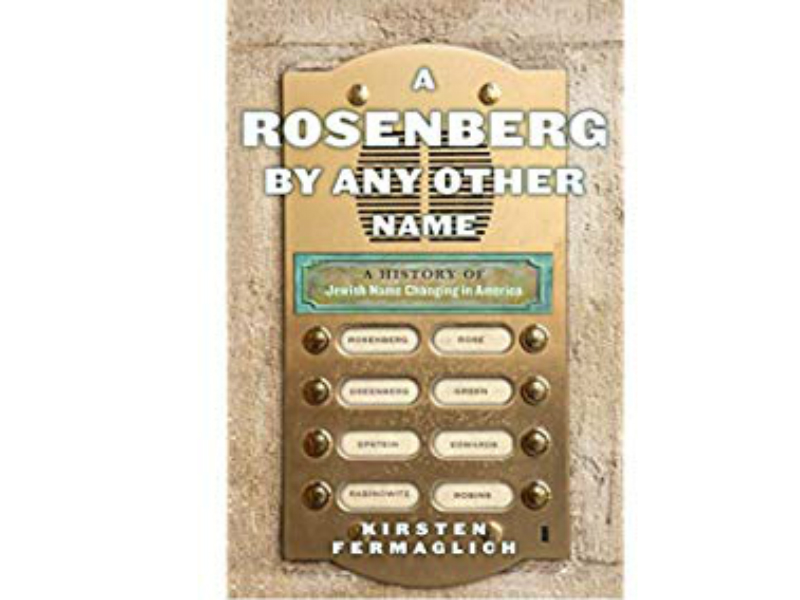

Although Jewish name-changing was widespread throughout the United States and Canada throughout much of the 20th century, no one has studied this interesting phenomenon at book length until now.

Kirsten Fermaglich based her study on thousands of name-change petitions that she found in the records of the New York City Civil Court, dating from 1887 to 2012. The documents include statements listing petitioners’ ages, residential addresses, occupations, nationalities and other details.

In New York state, one did not have to file legal papers in order to change one’s name: all you had to do was use a new name consistently and without any intent to commit fraud and one’s new name was legal. Still, many people sought to petition for official registration of their new names.

Fermaglich quickly debunks one of the most persistent myths of Jewish genealogy – that Ellis Island border agents capriciously changed the names of arriving immigrants. “Ellis Island officials were explicitly prohibited from changing immigrants’ names, and there is almost no evidence of official Ellis Island name changing,” she writes.

Most of the countless immigrants who changed their names in America were Jews. In New York in 1942, the proportion was about 66 per cent, followed by Slavic immigrants at 11 per cent and Italians at 8 per cent. The high proportion of Jewish name changers persisted until the 1980s.

Fermaglich cited a Canadian sociologist, Erving Goffman, who observed that Jewish name changers sought to avoid drawing attention to themselves; many faced repeated episodes of confusion, embarrassment and inconvenience because of their names. She found that most of the Jewish petitioners “darkly hinted” at the discreet anti-Semitism that often prevented them from advancing in the work world.

One applicant, Dora Sarietzky, a stenographer and typist, testified, “My name proved to be a great handicap in securing a position … In order to facilitate securing work, I assumed the name Doris Watson.”

The frustratingly long search for work before a name change was typically the most significant factor that applicants cited. Melvin Applebaum finally obtained a position, but only after he changed his name to Edmund Cronin. Bertram Levy became Bertram Leslie because his name “had been a hindrance to him in his efforts to gain an entrance to various firms and to secure business from them.” Lawrence Lipschitz, a traveling salesman, became Lawrence Lipson because “people out west” found it hard to pronounce or spell his name, leading to embarrassment and ridicule.

For Eli Simonovitz, who already had a position, it was his employer’s requirement that he post his name on a wooden plaque on his desk that motivated him to become Eli Simmons. “A name change allowed petitioners to go about their daily business without having their stigmatized names present troubles in every social and work interaction.”

Even after anti-discrimination laws came into effect, private institutions such as hospitals, universities, employment agencies and professional boards used application forms, which asked extensive questions about nationality and ancestry, in a covert attempt to identify Jews.

Questions may have included “What denomination are you?” and “Of what clubs, social or church organizations are you a member?” But less blatant questions, about the applicants’ place of birth and his parents’ full original names, also did the trick.

In the early 1950s a Jewish woman filed and won a lawsuit purporting she was passed over for a position as a direct result of such a questionnaire. The court astutely observed that discriminators “will not openly announce their intentions but will instead employ discriminatory practices in ways that are devious, by methods small and elusive.” The case, Holland v. Edward, set an important precedent and was subsequently quoted in many legal cases involving incidents of discrimination.

READ: MATTI FRIEDMAN IS A NATURAL-BORN STORYTELLER

Fermaglich presents numerous obscure and interesting articles, such as “I Changed My Name” (Atlantic Monthly, 1948) written anonymously by a New York Jew who jettisoned his name in favour of another that sounded less Jewish. The article struck a deep chord, sparked a provocative debate, and was republished in Reader’s Digest. Some respondents accused the anonymous author of abandoning, even betraying, the Jewish people.

For the article “Name Changing and What It Gets You” (Commentary, 1952) Alvin Kugelmass interviewed 25 subjects and was surprised to observe that none of them had any intent to pass as Gentile. “In no case could I sense even the remotest inkling of a wish to abandon their Jewishness,” he reported. Although there was some effort toward concealment of their Jewish background, the interviewees generally went to some lengths – outside of the workplace – to demonstrate that they were still Jews.

The author also unearthed a list of 106 distinctive Jewish names that psychologist Samuel Calmin Kohn developed in 1942 to help the Jewish Welfare Board conduct a census of Jews in the armed forces. Her survey on the subject even included Jewish name-changers in the fiction of American authors such as Philip Roth and Herman Wouk.

Ironically, while the Steinbergs became Stantons and the Greenbergs became Grants, these and many other name-changers overlooked the obvious fact that first names can also sound “too Jewish.” The comedian Lenny Bruce – formerly Leonard Alfred Schneider – once lampooned American presidential candidate Barry Goldwater (of the family Goldwasser) by observing, “Where is there a goy with the first name Barry?” But Bruce should have realized he could easily have been made the butt of the same joke. It was left to the American comic Rodney Dangerfield – formerly Jacob Cohen – to turn the tables by observing, “What kinda goy has a first name Lenny?”

Both entertaining and enlightening, A Rosenberg By Any Other Name comes up smelling, well, like a rose.