Hitler adored Mickey Mouse movies. For his birthday in 1937, Joseph Goebbels gave Hitler 12 Mickey Mouse films, including Mickey’s Fire Brigade and Mickey’s Polo Team. “He is extremely pleased,” the minister of propaganda wrote in his diary, “for this treasure that will hopefully bring him much joy and relaxation.” And meanwhile, as the Fuehrer was roaring with laughter at Mickey’s antics in his Berchsgaden lair, Stalin was clapping his knees with delight as he watched Charlie Chaplin films in his dacha.

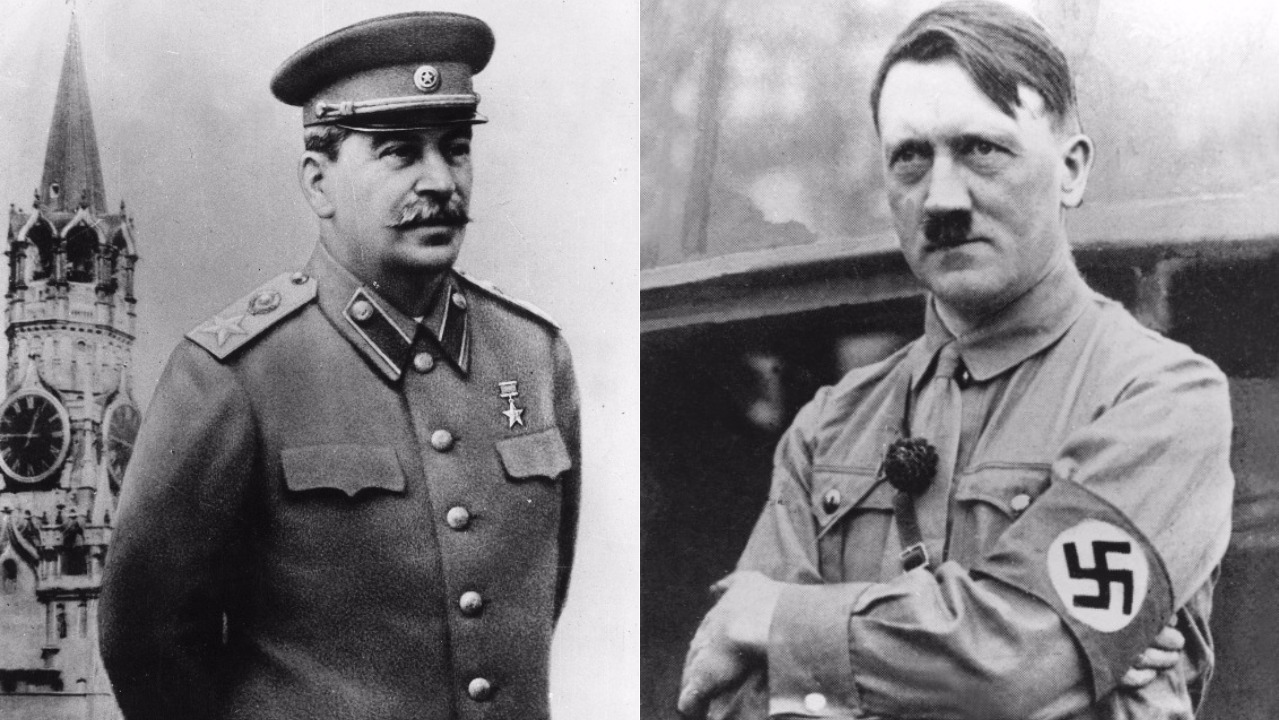

The two tyrants, who turned Eurasia into blood-soaked weeping meadows, had a great deal in common. Lord Alan Bullock, in his magisterial Hitler and Stalin Parallel Lives, draws attention to their narcissism. But it was in their infatuation with moving pictures as tools of propaganda and self-aggrandizement that their narcissism converged perfectly.

READ: THE DAY HITLER DIED DEBUTS INTERVIEWS WITH MEN, WOMEN IN HITLER’S BUNKER

Epic historical dramas on the silver screen exacerbated their larger than life self images as they transported themselves into the visual narrative medium, where superheroes changed the course of the world by performing impossible feats. They identified with their respective national icons depicted in historical films and conflated their destinies with the fates of mist-shrouded warrior knights whose epoch-making accomplishments were melodramatically magnified on the silver screen.

Seeing themselves as supreme actors on the global stage, both overlords stepped out of the darkened theatre and tried to mould the world in their own images with blood, iron and swords. Their enraptured “audiences” responded by adorning them with garlands and losing themselves in orgies of adulation. Hitler saw himself as anointed by Providence to save the German race while Stalin regarded himself as the ultimate personified manifestation of Dialectical Materialism ineluctably paving the way for the establishment of the first communist state in history.

One imagined that he was transfigured into a latter day Frederic the Great, the other reconfigured himself as a risen Ivan the Terrible.

As depicted in Andrei Konchalovsky’s film The Inner Circle, Stalin was a movie buff. He fervently believed in Lenin’s dictum that “Of all the arts, cinema for us is the most important.” Under Stalin, the Communist Party aimed at transforming the Soviet Union not only economically but also culturally under the aegis of a centrally planned cultural dictatorship where each image was scrutinized for its total conformity with socialist realism. Marx had once observed that revolution first started in the consciousness of the masses; Stalin was now determined to cement it with celluloid images engraved in the minds of the proletariat.

While Stalinism viewed Hollywood as the opium of the soul, it nevertheless saw a great deal of merit in films like Thief of Baghdad, Tarzan, James Cagney’s gangster thrillers, romantic musicals like the Great Waltz and John Ford movies. Like Hitler, Stalin supervised each Soviet film in minute detail: he, very much like his ultimate nemesis in Berlin, was at once censor, director, editor and, script writer. Stalin, in the same manner as Hitler, “suggested” films, chose subjects, selected the music, picked directors, intertwined actors, watched rough cuts, inserted and deleted whole scenes, ordered remakes and made or broke film directors, often killing those who deviated from the politically correct artistic “ism.”

In both cases, dictatorship begat a visual world which made mass murder both desirable and necessary. If the projected imagery of the Jew and the kulak is one of sewer rats scurrying like demented feral carriers of the Black Death or bats embedded in the flesh of the innocent, what could be more salutary for public hygiene than their total elimination? Demonization preceded the incandescent chimneys of Auschwitz and the frozen mass burial grounds of the Gulag.

READ: NETFLIX BUYS RIGHTS TO BORAT-STYLE COMEDY ABOUT HITLER

But it fell to one of Hitler’s first Jewish intellectual victims, Walter Benjamin, to discern a crucial difference between the two dictators’ approaches to cinematography. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin writes: “Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an esthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which fascism is rendering esthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.”

Benjamin committed suicide rather than live to witness the fulfilment of his prophecy.