Since her debut The Secret of Gabi’s Dresser—the story of her mother’s own survival during the Holocaust—was published in 1999, celebrated Canadian author Kathy Kacer has gone on to write dozens of novels, largely for younger readers.

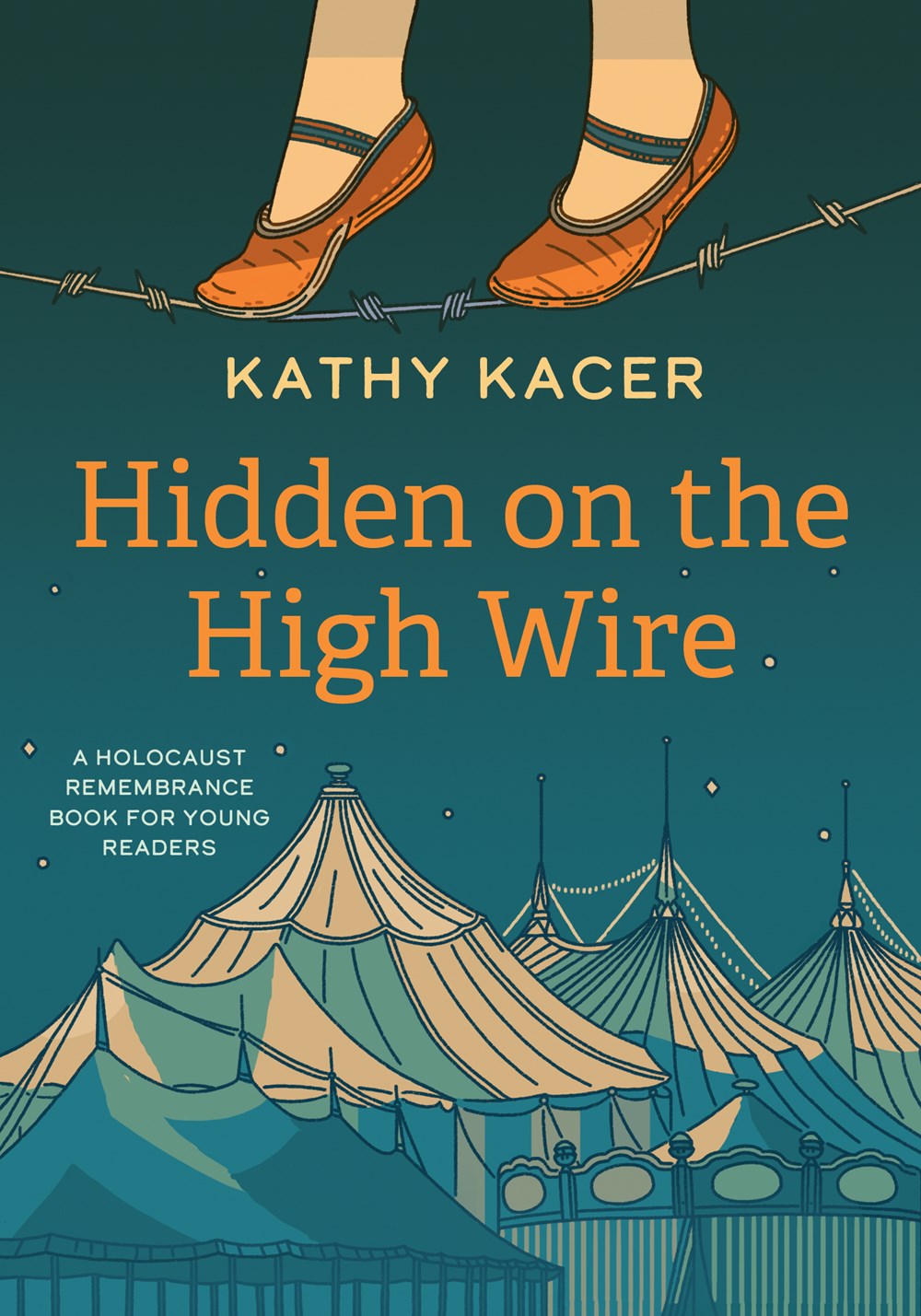

Hidden on the High Wire, her latest effort, was published on Sept. 27, 2022. Based on remarkably true events, it follows the story of Irene Danner, a young German-Jewish circus performer from a Jewish circus dynasty.

As the antisemitic policies of Hitler increase in their severity, Irene’s family is forced to sell the circus and her father, who is not Jewish, is sent to war. With their lives and safety hanging in balance, Irene boldly approaches Adolf Althoff of the Althoff Circus, pleading he take her and her mother into his employ. He agrees, and Irene tours with the Althoff Circus, performing on the high wire, all while hidden in plain sight.

Kathy Kacer spoke with The CJN’s book columnist Hannah Srour-Zackon about her book, the research process, and writing about the Holocaust for young audiences.

How did you come across this story and what drew you to select it as the basis for the book?

I was looking for stories of people who had rescued Jews during the Holocaust, which has become a passion of mine to write. I think the stories of survivors are critically important, but the stories of those who helped Jews are too, particularly in this time of rising antisemitism.

The story of the Althoff Circus and of Irene Danner, a circus performer from a Jewish circus dynasty which I thought was remarkable—whoever heard of a Jewish circus performer?—came up. The more I read about it, the more I felt it combined everything that I wanted. It’s the story of someone who was lucky to survive and of someone who helped, and that’s what really drew me into it.

What I found so moving and surprising with this story in particular was that the whole circus was willing to protect Irene and her family.

It’s pretty incredible, isn’t it? In the book’s historical note at the end, I talk about how everything I found and read really indicated that the members of the circus were willing to protect Irene and her family. There is a reported story of one disgruntled employee who complained and Althoff fired him on the spot.

When I’ve read stories of heroic individuals or Righteous Among the Nations, it is often the case that where there were strong leaders, there were others who were willing to fall in line behind them. I believe there’s strength in numbers. When you’re not alone in protecting, it becomes easier to do, and I feel that Althoff’s message to the members of his circus bound people together.

How did you go about doing the research for this book?

When you write, it must be from an authentic place, or at least convey something that’s authentic. I’ve never been on a high wire, and I have only been to the circus as a kid and later with my own kids. I researched everything: from descriptions of high wires to life in the circus in the 1930s to the specifics of the Lorch Family Circus (the Jewish circus) and the Althoff Circus (the circus where they hid) to everything I could get my hands on about Irene Danner, the Althoffs, and their lives.

I’m very fortunate as there is a fair amount that’s been written about both circuses. There are even some videos of Adolf Althoff speaking about his experience of having saved the Danners in his circus. I keep binders full of research notes, articles, and conversations. As I’m writing, if I get stuck I then will pause and go back to researching. It’s just a constant process of reading, reading, reading, and then reading some more.

When you actually began writing the book, how did you find that balance of incorporating elements of fiction in harmony with the history?

It’s an ongoing challenge when you’re writing historical fiction. I always have in mind that I need to write a story that is compelling for young readers, and I try to bring the characters to life as much as possible.

Based on what I’m reading and my research, I include dialogue that may not have happened but is reasonable to think could have happened and descriptions of places I haven’t been to (like the city of Darmstadt in my book).

We talk about two kinds of writers: the planners and the “pantsers.” Planners are people who meticulously plot out a story and its characters, and “pantsers” are people who fly by the seat of their pants. I am an absolute planner. Once I’ve got a lot of history in my head, I sit down and I say, “Okay where am I starting this story? What’s Chapter 1 going to look like? Chapter 2? Chapter 3?” Then I create a blueprint. I know I’ll be reinterpreting and changing that blueprint as I go along, but I do rely heavily on a plan to get there.

You’ve written numerous books for young readers about the Holocaust. What is your process for addressing such a difficult topic with a young audience?

After many years of writing these books I feel I have a “Holocaust radar.” I intrinsically know when I’ve gone too far or when I have to go further. But there’s no question I’m always making sure I’m sensitive to the age and stage of development of my readers.

I think my stories are fairly gentle in their approach with young readers. My editors help me see if I need to push further or if I need to pull back, and really help me balance.

It’s okay for kids to be moved by this history. It’s okay for kids to even be saddened by this history—it is a sad history. What we don’t want is for kids to be traumatized by this history and so I always tread that fine line of being true to history and not traumatizing my readers. It’s the people around me, it’s the experience that I’ve garnered over the years, and my own gut feeling about what’s right and what isn’t.

This is a topic that you’re quite well-versed in writing for this audience. Why the Holocaust and why for this age group?

I am the child of Holocaust survivors, so I grew up with this history—that’s where The Secret of Gabi’s Dresser came from, which is a story about my mother. I grew up in a family of talkers. Both my parents were very open with me about their experiences, and my parents somehow knew how to talk about this history in a way that didn’t terrify me. So I grew up really interested and wanting to know more, and more, and more.

I love writing for young people, I love writing in the voice of a child, I love thinking about a young audience, and I love bringing this history to them. I think on some level I’m recreating the experience I had listening to this history with my parents as a child and now I feel like I’m the adult who’s relaying this history to the next generation of young people.

It’s in keeping with that important storytelling and passing of history that I’ve done. I have written one book for adults, and I’ve written for an older adolescent audience as well, but that ‘middle-grade’ audience is really my sweet spot when it comes to writing these stories.

All this makes me think about rising antisemitism, as you alluded to. What do you hope that your readers will take away from this book and from all your works?

I don’t think we’ll ever get rid of antisemitism. It will be present in some form to some degree always. I’m not going to cure it; I wish I could. The only thing that I can do is create as many stories as I possibly can about this history and create them for a wide, young audience. I can also continue to speak in schools to young audiences, and encourage kids to read my books.

When I speak in schools and I’ve got an audience of about 150 kids, do I think that I’m going to move each and every one of them? No. But if I can influence five or 10 kids, or a group of kids, to be interested in what I’m saying and to read more, then I’ll feel I have done a good job and hopefully they will pass this information on as well. So what do I want for my readers? I want them to understand and be moved by the history, and I certainly want them to pass the stories and the history on to their friends and their family members, and maybe one day their children and their grandchildren as well.

One of the things that I really wanted to convey in Hidden on the High Wire is the notion that people are not necessarily who they appear to be. I deliberately included in this story different reactions. For instance, there was that little girl Andrea who appeared so innocent and sweet, yet was following the way her mother spoke about Jews. There was Bernard who appeared gruff and horrible on the outside, but he was the one who was helpful. And Martin, who was working with Irene on the high wire, was the one who spoke out against her. I loved playing with the notion that the truth only comes out when people are put to the test, and I think that was a really important part of this story.

What are you working on now?

I’m just finishing up a beautiful story, which was given to me by my publisher Margie Wolf of Second Story Press here in Toronto. She told me the story of a woman who went into Bergen-Belsen with her mother as a 12-year-old. Because of some circumstances her mother was able to bring two pieces of chocolate which she meant to keep for a time when she felt her daughter was too weak or sick. The mother ended up giving the chocolate to a woman who was pregnant and keeping her pregnancy a secret. She felt this woman was getting weaker and thought the chocolate would help her. This baby was born in Bergen-Belsen and survived. I’m not going to tell you the end of that story but that’s the one that I’m working on right now and writing as a picture book.

I have one more question I have to ask: Do you still have Gabi’s dresser?

I do! I would have kids knocking on my door periodically before the pandemic wanting to see the dresser. I love showing it to everyone and it’s still in remarkable shape. I keep inside it many of the things that my grandmother probably kept inside the dresser and I use it all the time. It is certainly the most precious piece of furniture that I own.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.