Portraits he painted from photographs of orphans who survived the Holocaust are the focus of Harry Tiefenbach’s latest art exhibition, Survivor Children.

Some were rescued in 1945 by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration from thr Flossenburg concentration camp. Their pictures, with their names on placards, were published in German newspapers in an effort to repatriate them to surviving families.

Other portraits are based on photographs of children he downloaded from the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. But he found no information beyond their names.

Tiefenbach’s parents are both Holocaust survivors. Born in 1946 in Poland, he says the Holocaust continued to haunt him from childhood onward. His mother, Lonia Belzyck, was interned in Auschwitz and his father, Leon Tiefenbach, survived by enlisting in the Russian army.

They met in his mother’s hometown in Poland, Tomaszow, where she returned after the war to find that the Nazis had given her family’s home to a Polish family. His mother was in the town square with three friends when they were approached by a Russian officer.

“That frightened them because if you were asked if you were a Jewish woman after the Holocaust it must have been terrifying,” Tiefenbach said.

But his mother pushed herself to the fore and said yes, that they were, and what did he want. The Russian officer, who was to become Tiefenbach’s father, was a Jewish resistance fighter who joined the army—and part of the unit that liberated Tomaszow.

The family immigrated to Israel, where his father fought in the War of Independence. In the early 1950s, they settled in Toronto.

Growing up, Tiefenbach heard about the Holocaust from his parents: “My father didn’t share much and my mother did a substantial amount.

“Part of my painting comes from trying to deal with those issues.”

“Mother and Child”

Tiefenbach painted it from an iconic photograph of a woman and a little girl running uphill from a train that had been liberated by American troops. In early April 1945, a few days before the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, three trains left that concentration camp in northwest Germany. Each carried 2,500 Jewish prisoners. After several days, one of the trains stopped and the Germans fled. American soldiers arrived and released the passengers. One of the soldiers, Maj. Clarence Benjamin, the deputy commander of the tank battalion that was on its way to help capture the German city of Magdeburg, took the picture of the woman and child. “To me the photograph is dark. It just refers to the circumstances,” Tiefenbach said. “I tried to give the painting a sense of colour, a sense of mystery and particularly the mother’s face, a sense of purpose. I took a little bit of innocence out of the child’s face.”

Lonia Belzyck

Tiefenbach said it was difficult to paint his mother from her identity card from the war years: “My mother was a bright woman with a lot of ambition about being an academic in Poland, but because she was Jewish and because she was a woman, she never had the opportunity to do that. The worst thing for her was that all of that was going to stick to her because she had to pose for an ID card as a young female Jewish person. I wanted to understand what was going through her mind. I repainted that image many times. I still can’t bond with it in the way that I wanted to, to get an understanding of how my mother felt the moment her ID picture, a Nazi identification card, had been taken. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to understand.”

Janusz Karpuk

The artist makes intuitive assumptions about who his subjects are when he paints them. Janusz struck Tiefenbach as an uncomplicated kid who might be on his team in the schoolyard, but not a close friend: “He struck me as being a very simple soul and the look on his face is kind of that way. There’s a sense of what has happened, but there’s also a sense of him being a simple soul. This helped him survive a horror that was unspeakable. His nature was an asset in his survival. That’s straight speculation on my part and I guess I need to do those things when I paint.”

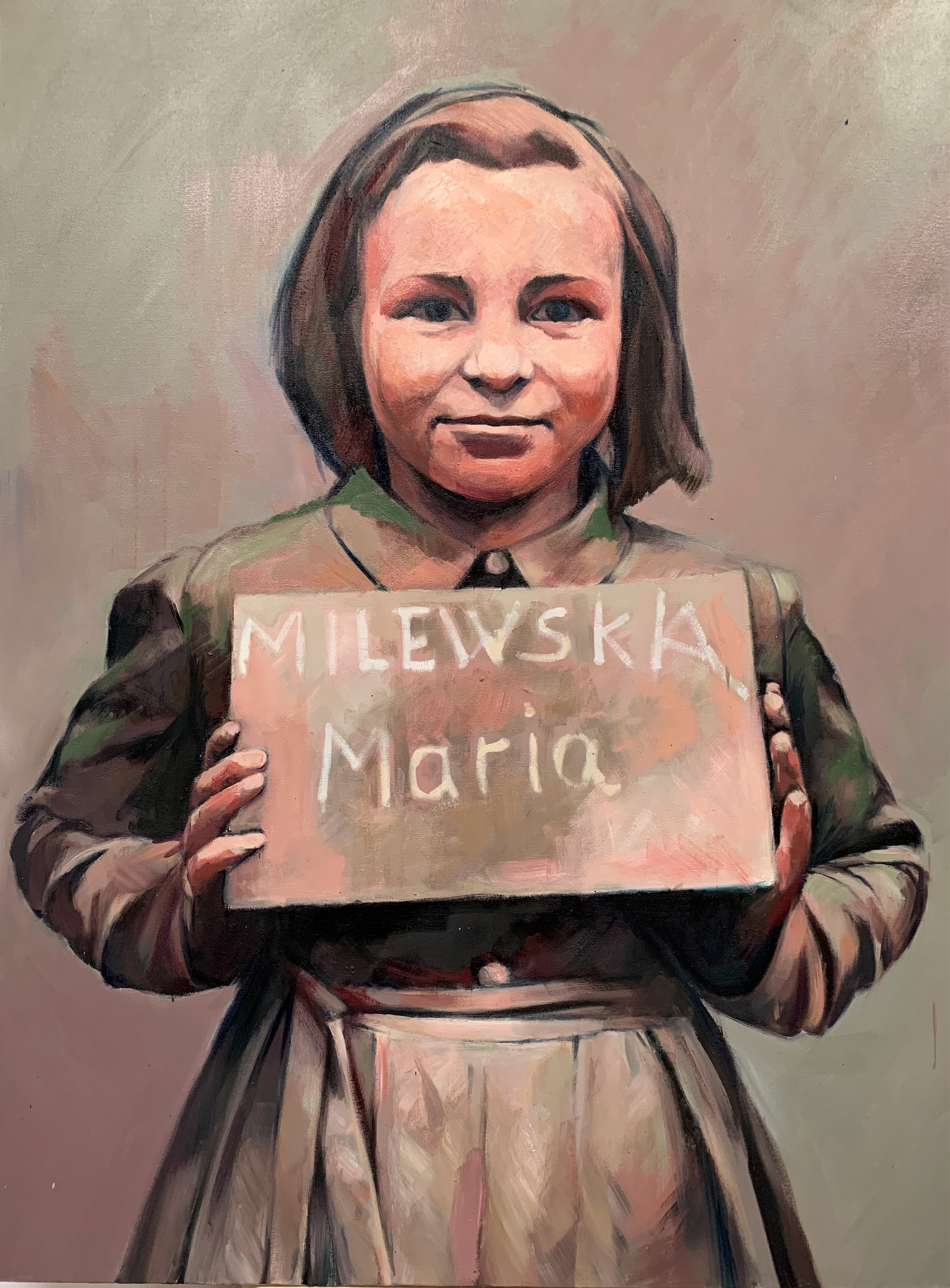

Maria Milewska and Jan Milewski

Tiefenbach saw Maria and Jan were both born in the town of Brody (in present-day Ukraine, near Lwów, Poland) and thought it might just be a coincidence. But when he painted their portraits, he noticed they both have the same kind of facial bone structures and he suspects they’re related: “I had the same sensations painting both of them. This is strictly a shot in the dark on my part.” He sees Jan as a very angry young man who survived because of his toughness. Maria struck him as someone who has an indomitable spirit and has what it takes to be a survivor: “I painted Maria in a warm way and made her eyes dark, so they felt like they were penetrating, as if the strength she has is a deep inner strength.”

“Boy in Prison Stripes”

Tiefenbach painted this portrait from a photograph he downloaded before he saw the movie The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. When he saw the film, he decided as a way of experiencing it, he would paint this child who was wearing prison stripes in the photograph: “As I painted him, I thought this image looks like a toothpaste commercial but is actually quite dark. Part of his hair has been shaved and there’s some damage at the side of the head. That’s conjecture, I have no way of knowing if that is true. It struck me as an interesting painterly way to make the point that while this child may look like he’s irrepressible, there’s a dark side. Kids were marked and damaged for their lives even though they survived. They may have survived the Holocaust, but look what they had to carry through life.”

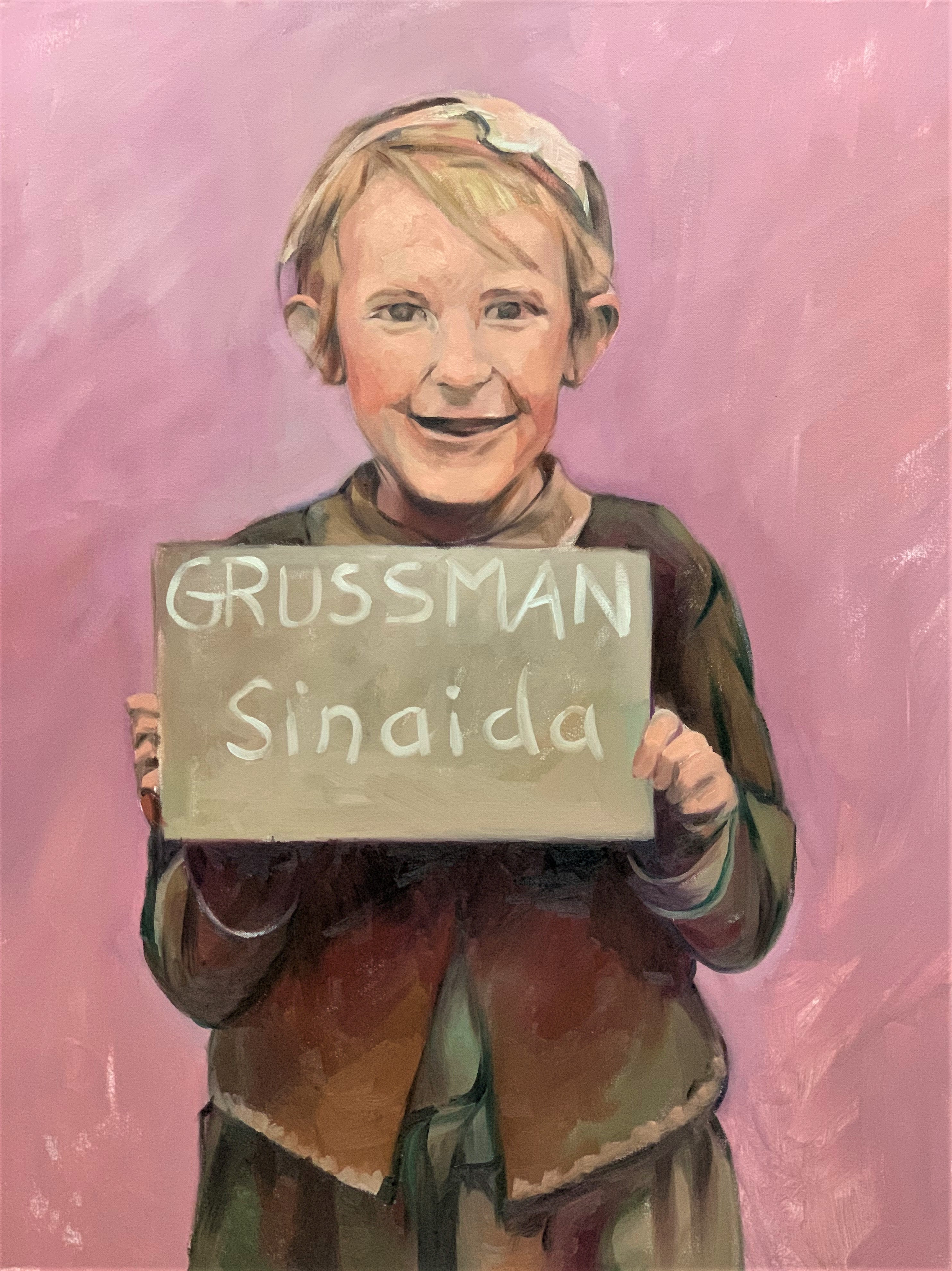

Sinaida Grussman

This is the second portrait Tiefenbach painted—because he finds her endlessly fascinating. “The girl feels kind of psychotic, like the damage she’s experienced is really quite deep,” he said of his response to her photograph. “She’s learned that the world requires something of her, it requires her to smile, to be obedient in the way she’s holding the placard, as if she’s been instructed to hold it just right.” Tiefenbach was hoping to give Sinaida strength from the colours he used in the portrait: “I put her in a rosy space, I gave her this lovely brown coat. I tried to make her eyes show strength rather than panic.”

Survivor Children is a virtual exhibit presented by the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre and can be viewed until Nov. 30 at mnjcc.org/visualarts