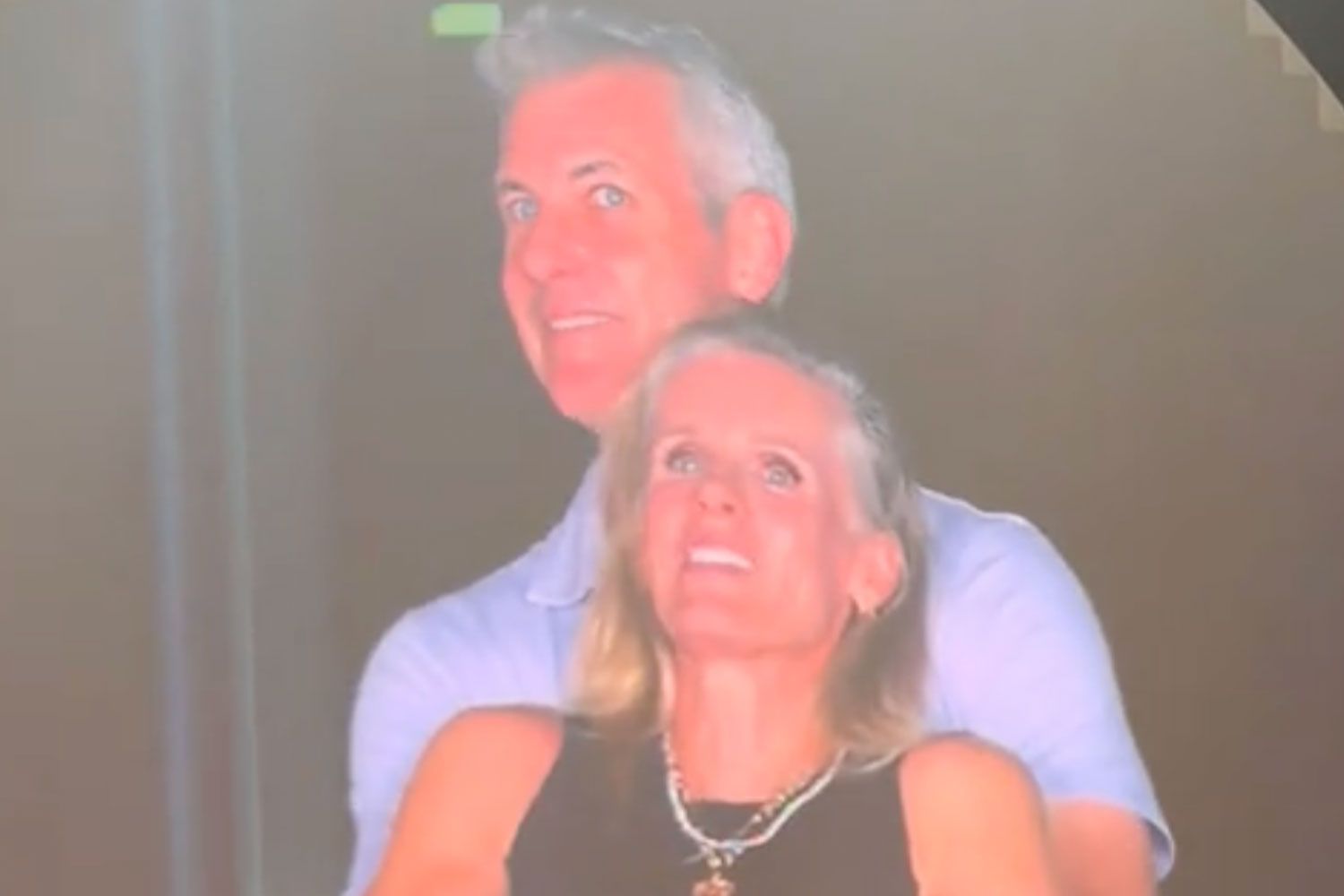

To our knowledge, neither the now-former CEO of tech company Astronomer, nor the company’s now-former head of HR, are Jewish. The secretive couple—who were having an affair that was famously caught by a videographer behind the Jumbotron of a Coldplay concert—instantly became a viral sensation, sparking waves of ridicule and resulting in their departure from the company.

But The Jewish Angle podcast host Phoebe Maltz Bovy had to ask: is it lashon hara to speak of these people behind their backs? So she asked The CJN’s resident rabbi, Avi Finegold, to shed light on the situation. It’s not quite lashon hara if the secret has been put out in the open by a Jumbotron, but that doesn’t quash the ick factor from giddily discussing people’s personal lives on social media.

Plus: why wasn’t this seen as a #MeToo echo, given the power imbalance between the CEO and lower-level female employee? Listen to The Jewish Angle above to find out.

Transcript

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Hi, I’m Phoebe Maltz Bovy and you’re listening to The Jewish Angle, a podcast from The CJN, where I look at Jews’ complicated place in today’s cultural and political landscape. So the story I’m going to tell today is about a man and a woman, both married to other people. They went together to a Coldplay concert in Massachusetts, in the United States, where they were seen on a Jumbotron—something I did not realize non-sporting events even had—cuddled a little bit. And soon they realized that they were on this Jumbotron, ducked away, and the rest is history. I learned about this story on social media, but later I learned it’s just been on TV. Like in doctor’s offices, dentist’s offices, they have, you know, like that TV screen that just has all the sort of news of the day with like traffic reports and so forth. It’s been on that. It’s like that level of story. It became a huge meme. The store Ikea took part in the meme by putting stuffed animals kind of cuddled the way that this man and woman were. And there have also been professional repercussions for this couple because the man is the CEO of—or was, I should say until recently—the CEO of a tech company I’d never heard of. And the woman did HR for the selfsame company. Now you might wonder why I am bringing this up on a Jewish podcast. Is it that these people are Jewish? They do not ping my judar, and from what I’ve googled, it does not seem that way. But it’s just that there was something kind of primal and biblical about the stakes here. Both the way that infidelity can still dominate a news cycle, even in all this talk about sort of open relationships and modern ways of arranging things, that this could still be like “man cheats on wife: breaking news.” But also even more so, I was thinking about the ethics of having a big gossip about it. And specifically like, as you may notice, I have the names of these people. Like I know what they are, but I feel squicky saying them. I don’t even know if I’m supposed to. Here to help figure all of this out from more of a religious and ethical perspective is Rabbi Avi Feingold. Avi, welcome to The Jewish Angle.

Avi Finegold: I’m so glad to be here.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Avi hosts the “Not in Heaven” podcast from The CJN, and, as I do, writes for Scribe Quarterly, The CJN’s quarterly print publication. And we used to be on a Bonjour Chai together.

Avi Finegold: We. We were co-hosts. Bonjour Chai. That was like—how did you not lead with that one?

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, it’s very appropriate because we were always talking about when we split off to do our own podcast, that it was this conscious uncoupling. And, you know, the origin of that.

Avi Finegold: Expression, of course, is Gwyneth Paltrow.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: And who was she consciously uncoupling from?

Avi Finegold: Chris Martin of band Coldplay.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: There you go.

Avi Finegold: All comes back to Coldplay.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: So there was no question who would be the guest for this one, assuming you agreed, which thankfully, you did. So I want to know, first of all, like, what are the Jewish ethics of having a gossip about this? But first, specifically, because I know you have given this a lot of thought, the concept of—is it Lashon or Loshon Hara?

Avi Finegold: Lashon.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Lashon.

Avi Finegold: It depends. If you’re Ashkenazi, you would say Lashon Hara, or if you’re speaking in a more modern, Hebrew, Sephardic context, you’d say Lashon Hara. But it’s the same thing. Literally, it means like evil speech or speech that is not good. And I think it has a much broader context of what that actually is. And so, you know, whether you’re gossiping, whether you’re talebearing, whether you’re lying—you know, in today’s day and age, that refers to gossip and tale-bearing and, you know, libel and things like that. But yeah, the idea of Lashon Hara is this encompassing thing to make sure that your speech is good.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: So, verdict? If you know about this case, this story, is it okay to speak of it so Jewishly?

Avi Finegold: One of the ways in which, and I actually just wrote about this, which will be coming out in upcoming Scribe Quarterly for the fall. We just had the summer issue come out, and the fall issue will have a piece about Lashon Hara. And that’s kind of why I thought about it, because I hadn’t spent too much time thinking about it until now. The idea about what makes Lashon Hara, what makes gossip evil in this case or in cases in general, is that it maligns somebody and especially maligns somebody without them being around to talk about it. The big exception that you see in a lot of the legal literature is when they say, well, when it’s for the good, you’re allowed to actually speak what might otherwise be considered Lashon Hara. So a great example of that is MeToo, right? Not me personally. Hashtag MeToo. In the era of, you know, when MeToo was cresting, and you heard a lot of people say that. The thing that stopped me from talking about my abuse was when I spoke to my rabbi, he was like, well, don’t talk about it because it’s Lashon Hara. And people would be kept down because of the gossip. And yet the thing that people talk about now is that not only is it allowed, but it’s mandated to be able to talk about an abuser because that is going to prevent other people from being the victims of abuse. A good barometer for being able to think about how you should regulate how you should think about your speech is—is this gonna benefit anybody, or is this just there to be gossipy and fun and light or whatnot? In this situation, you know, if there was no kiss cam, if somebody was at the concert and saw these two, these people’s spouses, then they might be in a good position to say, yes, I should be telling their spouses. And that might not be considered gossip. Right? But if everybody knows about this thing already, why would you be needing to talk about it? Other than to embarrass them further, to malign them further, that is kind of icky. And so that’s where you can start thinking about the notion about Lashon Hara. I had a colleague of mine tell me, and this is a good way of doing it—he was a therapist and he said, you know, in therapy and in a lot of justice work, you hear this line, “nothing about us without us.” I’m sure you’ve heard this before. Don’t try to fix indigenous rights without indigenous people at the table, et cetera, et cetera. Don’t talk about somebody without them present. And if somebody is present there and you feel that it’s important to talk to them, it’s complicated. But if it’s beneficial and useful, then, you know, that’s a good way of being able to frame the Jewish approach of Lashon Hara.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: No, it’s so interesting. So the MeToo aspect, MeToo is going to come up later in this conversation regarding a question I have about this case. But, yeah, it’s tricky because, like, sometimes there, though some of the accusations, it’s not even about, like, true or false accusations. But, like, I’m thinking of things like the Shitty Media Men list, which included just this sort of crowdsourced document that was about misdeeds of men in media. Some of the things were either not substantiated or just kind of off topic. Like, they weren’t. They were just like somebody was annoying at someone’s work, and they put it on what seemed to be like a crowdsourced document for finding abusers. And, like, yeah, it’s just because, you know, I think a lot. Me too. Was a lot of different things, which is complicated. But, like, when I think about the ethics of this in a more secular way, I think about this as, like. And I don’t know whether there’s a Jewish sort of convergence with this whatever, but, like, don’t turn people into a meme. It seems to be like something. I think of it that it’s, like, it’s inevitable that it happens but also, like, it’s never really ethical when real people become a meme, you know. And also just this question of, like, treating real people interchangeably with fictional characters, which is something that I remember noticing when I reviewed Naomi Klein’s book. I was. Because it’s about the double thing, I always have to, like, pause. You know, Naomi Klein, where she’s talking about Naomi Wolf in this kind of almost interchangeable way with a Philip Roth character. And it’s like, one of these is a real person, and one of these is a fictional creation. And I feel like something ethical seems squeaky. It’s all about Squicky. The Squicky theory, to me, about, like, if you talk about a real person in a way where you imagine that they’re a fictional creation and that they don’t have any feelings.

Avi Finegold: Yeah. You know, I feel like we’ve talked about this in the past when it came to, like, celebrity. The notion that, like, there are some people who just by virtue of them being so public inevitably become just a thing and not a person with feelings. And, you know, there’s something that Kate Middleton.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: This is when we talked about the Kate Middleton story, where there was all of this gossip about a missing princess. And then, of course, it turned out to be a very sad story that she was very ill.

Avi Finegold: So the thing that I find interesting about that, and I try to make a distinction, is that, you know, in that situation, when somebody is a celebrity, they have willingly signed up to become a celebrity, and they know that they are going to become a caricature to everybody. Billions of people are going to develop, millions, whatever, tens of thousands are going to develop quote unquote, parasocial relationships with them, and they have to deal with that attendant, you know, whatever that is, that’s what it is. So I, I get that they have feelings. I try to empathize with somebody who’s a celebrity, who’s telling you how hard, tough their life is, whatever it is. But I also, like, like, okay, you signed up for it. I’m not treating you like a total person because you’re a Persona you. That is who you are when somebody does something inadvertently. And I’m bracketing our couple in question here, how a divergent they were is a different story. When something happens to you inadvertently and you become a meme, like, yeah, that’s not good. I don’t like. I really, really don’t like that. That’s the squickiness that you feel, that you’re talking about. That to me is the distinction. They didn’t do anything, and then something just happened, and now they become like the meme. The part that I have to figure out in this case is that, like, these people did something very shameful. They didn’t think that they would get caught by it. But we’re in an era where it’s very easy to get caught by these things, and I hope that this is a way for people to be able to recognize that, yes, we live in an era where things get caught much easier and they’re dealing with the attendant shame, and yet everybody’s turning them into a meme now. And even though it’s kind of funny, you kind of feel for them a little bit in that way, even though, you know, the shame that they’re feeling is real and the. They didn’t ask for this in their own way.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Right. So you just touched upon actually like three different things I have separate questions about, so I’m going to try to.

Avi Finegold: That’s how we work.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Break this up into pieces here. So I know actually from talking with Kat Rosenfield, we were talking about this and she’s.

Avi Finegold: She’s the other woman in this situation.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: She is the other woman. Exactly.

Avi Finegold: If I see you guys at a Coldplay concert on the jumbotron, I’m gonna feel so hurt.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, when we were having our illicit conversation about this, she was saying that there have been like sort of social conservative arguments along the lines of these people were cheating. This is Setting an example to. To make a big thing of this is setting an example so that other people don’t cheat. And I’m wondering, like, would there be, like, would Judaism be, like, where would Judaism stand on that? Like, should. Should one make a big example of into an individual case of alleged infidelity?

Avi Finegold: So this is actually really interesting that you bring it up this week because just this past week’s Torah portion actually has this story. And it’s fascinating what happens with the story and with the aftermath throughout history. So there’s an episode where non-Israelite women are found to be consorting en masse with Israelite men in the desert before they enter into the land of Israel.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: The shiksa portion, yes.

Avi Finegold: I’m not going to get into what they are, the Moabites, the Ammonites, whatever it is. And this guy, Pinchas, Phineas, as one would call him in the Christian Bible, Phineas goes and is so struck by zeal for the rightness and the righteousness of doing the thing that is right. He finds this couple in flagrante delicto, as one would say it, and according to the midrashic sources or whatever it is, spears them together, right? So that one could not deny that these people were doing whatever it is that they were doing, and then hoists.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Them up, makes the public seem very.

Avi Finegold: Humane, kills them essentially, but then publicly shows them that this is what, you know, this is what should happen to people that do this kind of thing, that commit adultery or that sleep with non-Jewish whatever it is. And the rabbis have such a hard time with this because they know that this is a wrong act to go and not only shame somebody but to be the one in charge of shaming them and to have vigilante justice to do it. And they don’t want this to happen. And yet this man seems to be clearly a righteous individual in the Bible. And so what seems to like the consensus view, meaning there’s always outliers in both directions. You see, you have this like, well, you shouldn’t do it. But if you know for sure that you are right in terms of your vigilante justice that you’re about to commit, then you’re allowed to do it. But we don’t do that anymore because we can never really be sure. So they basically exclude every example except for him and say, you don’t do this because that’s not what you’re supposed to do. And you’re not supposed to shame people for doing this. You’re supposed to just, you know, the setting of example isn’t necessarily the right way to approach it.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, it’s interesting when you say about the like the not being sure because I saw this story and I thought, you know, what if this is. These people are all in open marriages, open privately, but publicly trying to have the appearance, obviously not trying very hard, but trying to have the appearance of monogamy. And you don’t actually know if you are outside these people’s marriages what their arrangements are and whether they are in fact wronging one another. You know what I mean? Like this is something where.

Avi Finegold: Yeah, I mean in this case, I think it’s not the case because had that been the thing, they probably would have rather been outed as, you know, a swinging couple rather than. Or ethically non-monogamous. Right. I think they probably would rather do that than really. I don’t know.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I don’t know. I don’t know. I mean, the reason I’m saying I’m not sure is because I think there’s a dignity involved in life, and if your spouse kind of violates your dignity, I could see there being a woman in the world, or a man in the world, whatever, who would be more okay with their partner discreetly getting a bit of action on the side than going to a Coldplay concert and having this be public and being on the Jumbotron and all of this.

Avi Finegold: Yeah, yeah. In that sense, you’re right. I meant that like if they were all in on the.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Oh, you mean if it was like truly, Truly. Yeah, yeah.

Avi Finegold: And they were ashamed because they were private about it, you know, they were kind of religious. They didn’t want people to know that, yes, this is what we do and this is how we do it. Then that I think they probably would have gone for the lesser shame, but especially because there’s no shame anymore in ethical non-monogamy. Everybody does it.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I don’t know. I mean, that’s the thing is I can’t really tell because I did feel like there was something very of another era about this. But I’ll get to another way that I think things were of another era. But if you. Did you have something else on this?

Avi Finegold: No, no, I was just thinking that like, you know, nowadays that the thing to do is it’s ethical non-monogamy. And in a bygone era which you’re about to talk about, it was very much ethical non-ethical monogamy. That was the, that was the thing to do in the day.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, this is going to be about a bygone era, but in a different way. Which is something that struck me about this, and partly it struck me because tonight we are recording on Tuesday, July 22; I am actually going to be at an event with Lydia Perovic, remember her?

Avi Finegold: Oh, I remember her, yeah.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Sorry, not speaking very well today. But anyway, we’re going to be appearing at something that she organized to talk about MeToo and what came of MeToo.

Avi Finegold: When you say you’re appearing together physically, not on a Jumbotron.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, I would have a lot more explaining to do perhaps than she would, but no, not on a Jumbotron that I know of. She hasn’t told me if there’s going to be a Jumbotron. I’m not appearing if there’s no Jumbotrons. But no, those are just for the audience members. Anyway, it’s about MeToo. And so MeToo has been very much on my mind again this week. I was thinking about it in terms of this Epstein stuff in various ways, but also the Jeffrey Epstein, obviously, not just Epsteins generally, but here specifically, we have a case where this man was until recently the head of a company, not a company I’d ever heard of. That’s going to be relevant to my next question, probably, but yeah, and she is or was an employee of the same company. Normally in a MeToo framework, you would be thinking, okay, here’s a female subordinate in some kind of what looks like intimate situation with her male boss. It would at least come up as a possibility that there was coercion. And what I have found so striking in this particular context is how absent that has been as a possibility at all. Like that does not seem to have come up. What do you make of that? That’s not really a Jewish question. It’s just like something, I mean, my.

Avi Finegold: First question, my first thought, my first thought is, well, at least HR knew about it.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, that did come. A lot was said about the HR thing.

Avi Finegold: So yeah, look, I’m a big believer in the coercive possibilities of relationships. You know, I, I remember learning this when I was doing my BA in psychology and learning that therapists that you either have like some therapists believe it’s like a seven or ten year window to be able to date a former patient. And a lot of therapists say that, no, you can never date a former patient. If they were ever a patient of yours, you might actually be in a coercive position; you might be in a position of power over them. Same thing with teachers and TAs. And we see this all the. And there’s this notion that I don’t like that if it’s quote, unquote, you know, consensual, if they are both adult enough to be consenting, then they are both adult enough. And that’s legally, I believe the true, you know, fact around this, that consent is, doesn’t matter, then you’re willing to give up whatever that is. But I am with you that I do very much believe that the power dynamic is very weird in a relationship and in, you know, in some of these. And I think that as a result, people should be ethically, you know, barred from certain types of relationships. But in this case, even if you ethically barred this person, you said you’re the CEO, you’re not allowed to date even if you’re single. This person clearly, you know, and I’m not sure I’m. I don’t know, I’m. I’m guessing here, but this person does not seem to have the same level of scruples to go and say, well, you’re right, we should have an affair, but you know what, I’m going to promote you to the C level so that we can actually have an affair. And it won’t be, it’ll be ethical in that sense. But my wife, you know, whatever, we’re not going to get into that. So, like, in that sense, yes, I think that that’s a big part of it, but we only see that come up when consent is like a question around what that consent is. And yes, I think we should be having a larger question about certain relationships and what consent means in those relationships.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I mean, I just found it very strange. This is one coming up. I. My gut feeling, and I wonder how much was just colored by the discourse on this was, oh, these are people having an affair. They’re, as others have pointed out to me, close in age. You know, they look happy in that moment before. They really don’t look happy. But like, who knows? And I don’t find the fact that she’s not a young woman all that definitive. She could still really want to keep her job and think that’s what she has to do to do that. And that would be very MeToo-ish.

Avi Finegold: Yeah, I’m with you. I think that it’s, you know, there probably are better guidelines that we should be having for these things, but I’ve never worked in a large corporation like that, so I really, you know, I have no frame of reference for this type of thinking aside from knowing that relationships can be messy, and then if there’s even a hint of messiness. I do believe that you should avoid them. So.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I don’t know that, like, I don’t feel like I’m advocating for necessarily that there needs to be a MeToo analysis of this couple. I’m just struck by the fact that there hasn’t been one. And it seems like it should at least be out there. You know what I mean?

Avi Finegold: I think it’s because what I’m trying to get at is I think that the issue here is that there has been an absence of discussion around anything involving consenting adults.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: But there hasn’t. But what I’m getting at is that there hasn’t. For years there were.

Avi Finegold: As I just said, there has not been a conversation about this. When you have two people relatively close in age but have a weird power dynamic, it comes up in the context of conversations with, like, therapists. It sometimes comes up in conversations with professors. And even with professors, you’re like, well, if the TA is over 18 or the student.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Oh, no, no, no. It has come up very much with that.

Avi Finegold: If the student is no longer a student, then that’s not a problem anymore.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: A bunch of schools have, I think, more rules about this than they used to.

Avi Finegold: Well, that’s good.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: But there is. There is a Me Too. Like, I think because what I think is that Me Too has sometimes, like the sort of, by Me Too, I mean, like the cultural kind of fallout from Me Too has sometimes overshot the mark where it’s like. And kind of done a micro analysis of power dynamics such that like, nobody could ever date anybody ever. This seems like the kind of case that would not require a micro-level. Like, who knows? I don’t know. I mean, you know, she’s not, to my knowledge. I don’t know.

Avi Finegold: So I’m gonna give them the benefit of that on this one in that, like, maybe she’s in a totally different division and he doesn’t have the ability to really let her go. Like, he’s so far removed from the process as the CEO that, in reality, I don’t know. I don’t know how these things work. And I would imagine that there are some cases where the power dynamic of being the CEO and somebody else being lower but being in a completely different, you know, something or other would not matter, would not make a difference.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I will plead.

Avi Finegold: Or make less of a difference.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I will plead corporate ignorance alongside. I wanted to ask you, though, something I saw on Blue Sky, which I should probably not use because it just fries my brain like little else. It’s this liberal progressive, kind of the nicer alternative to Twitter, which is like a kind of weird place where somebody there was really at. Well, first, somebody posted that you really shouldn’t be gossiping about these people, you know, and then somebody replied to say, no, no, you should because it’s punching up. And was using the punch up versus punch down thing and claiming that because these are like wealthy people or powerful people, though, I don’t know how powerful the woman in this relationship could plausibly be. And that to me seemed like a stretch.

Avi Finegold: I mean, to me, that’s not even. That’s very akin to saying Luigi Mangione is a great hero. Right. Because he was punching up and all the people that followed him because he was punching up. And I’m like, yeah, no, I really, that never justifies anything. To go and say, well, you’re sticking it to the man. Especially where in this situation, at least in the case of Luigi Mangione, you can go and say, well, he did something terribly wrong because of the punching up thing. Right. Whereas in this situation, this couple had nothing to do with like the scandal. The thing which they are shamed for has nothing to do with their corporateness.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Right, Right. It seems.

Avi Finegold: And so therefore you’re not really punching up. You’re just saying, oh, rich people have the same problems that we do.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, the reason it seemed like a stretch was because this company called Astronomer, I had never heard of. I asked my husband, who is an astronomer, like, have you ever heard of the company Astronomer? And he had not. Like we’re, this is not like, this is not Google, you know what I mean? This is not some like extremely influential thing. And it’s like it to. It reminded me, okay, this is going to be a little bit galaxy brained, but it reminded me of when people talk about either Lena Dunham or New York mayoral candidate Zoran Mandami as being Nepo babies because they have like slightly notable parents who don’t do the same thing that they do. It seems like one of these things where like you’re describing as a powerful person, like somebody gainfully employed and good at what they do. But like, are these really like the. You know what I mean? Like, this is not the president. This is not the president. This is not like the Prime Minister. This is like, these are, these are people, you know.

Avi Finegold: You don’t know Astronomer the same way you don’t know Brian Thompson. Right? Who’s Brian Thompson?

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Who is Brian Thompson?

Avi Finegold: Brian Thompson is the person that Luigi Mangione killed.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Right, right, right. Like, so, like, I’m not gonna, and I’m not likely to meet him. Yes.

Avi Finegold: Yeah, but you see what I’m getting at that, like, the fact is that, and in that situation again, the thing that happened was because of the punching up. In this case, the only reason why you know about this thing is because it’s a big company if you’re in a certain field, and it’s not if you’re not. And so you don’t need to know everything about everything. But when something happens that’s notable, great, this person now gets stuck in the limelight. That’s like, I don’t, I don’t, I don’t know, like, there’s no connection in my mind to like, I’m not interested in like, I don’t need to know these things. It doesn’t make them better because they are CEOs of large firms of like large but unheard of firms. And it just highlights, by the way, like how many massive corporations are out there that we have no idea about that are doing big things that we are just completely unaware about. And, like, we like to point fingers at Google and this and Amazon and all these things. And I’m like, trust me, there are a lot of second-tier and third-tier companies that you can get really, really mad at for doing very, you know, I have no idea what they’re doing. I’m not saying that Astronomer does anything nefarious. I’m just saying that there’s this whole world that, well, I hope they don’t.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Manufacture Jumbotrons, because that would be very awkward.

Avi Finegold: That would be.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: But I think it does have something to do with like data in some way that people had some kind of convoluted. I have one more question. I mean, I have a million more questions. I’m going to pare it down to one. So, which is kind of going to be a bit abstract, but it’s really about where Judaism is on sanctimony. Because my impulse when I saw this story was this mix of it’s not right to make fun of it, it’s not right to have a laugh about it. And also, but like holding also like some space in my head was this is objectively extremely funny. And that’s why it is making the Renaissance funny, titillating, awkward, newsworthy. This is the kind of thing that was going to be a huge story. This was the kind of thing that people were going to speak about. And I’m wondering this is going to seem like is it considered or whether these are the Jewish ethics or how you interpret it, whatever, like, is it unethical to be like this? We should not be gossiping about this extremely juicy story which I’m going to tell you about now. Do you see what I’m saying? That’s a little bit like, yeah, I.

Avi Finegold: Mean, that definitely falls into the Lashon Hara category. I think the sanctimony thing is an interesting question of like, you know, is it useful, is it productive to be sanctimonious? I can’t think of many, if any, cases that it actually would be. And I know that there are probably plenty of rabbis that say sanctimony is evil. It’s not good to be sanctimonious. You’re not supposed to do that. While as soon as there is something that they think is evil and they have sanct, like they’re feeling sanctimonious about, they’re not even realizing that they’re actually like doing that. I can think of many cases where that has happened, you know, to go and see, you know, a rabbi who goes and says, “yes, those people, those evil liberal Jews, well, we’re supposed to all be friends.” We’re supposed to be friends. It’s not fair to hate other Jews in that as soon as somebody liberal and Jewish goes and like, you know, and this isn’t straw man, I can think of many, many situations where this has happened where they’ll go on point, “you see, you see, it’s because they don’t do X that that’s why,” you know, they get punished and we are righteous and we’re doing that. That’s pure sanctimony. And that’s not a productive thing. It doesn’t mean make your followers, it doesn’t make religious Jews go and say, “well, now I have to be religious because look at what happens to those people.” It’s not useful to me. The highest reason why one shouldn’t shame these other people is because our lives are young, and you have no idea when you are about to be shamed for something else also. I mean, in addition to the ultimate. Yes, you shouldn’t shame them because it’s a wrong thing to do. But even at a purely utilitarian level, right, the potential for shame, for something real, as ethical as we all are and going forward and doing the right thing, as we all are all the time, shame sometimes happens in the most unexpected ways. And you might be on a Jumbotron doing something very shameful. And you know, when you’re stuck and, and you don’t know what to do, and that’s. And then you say, like, I wish there was less shame in the world.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I have one pitch to you for something you could write about for the magazine, for Scribe Quarterly.

Avi Finegold: Okay.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Although I don’t know if it would fit The Jewish Angle on virtue signaling.

Avi Finegold: Yeah, that should. It’s. You’d be surprised. There’s more than you would think to. To say about that. And a good example of that is. And I’ll unpack it just a little here for you. I don’t know if I would end up writing it, but I’ll start it here and I’ll think about it. You know, ritual stringencies are a really fascinating thing. Right. There’s always some way to be more ritually stringent. I have a rabbi who always likes to point out that every. There’s no such thing as a stringency because every stringency is a leniency in the other direction. Like spending the money on this super kosher item instead of the regular kosher item means that you have $50 less to go and, you know, give somebody else food that they didn’t have $50 worth of. Right. So you’re asking yourself, how much is my religious stringency worth? Is it worth that $50? Or is it more important that I take that and take a regular kosher and just give that money to somebody who needs it much more than I do? Right. So that’s, you know, a good example of that. But in an era where luxuries were always often frowned upon, which is no longer the case because Orthodox Jews are very ostentatious when they can and need to be, or whenever they often, when they choose, stringencies became a luxury commodity. Right. To be able to say I can afford to do X was a. A really easy way to show that you’re like, you’re, you’re, you’re rich and you can. And you’re very, very religious by doing that. And if that’s not. If that’s not virtue signaling, if that’s not virtue signaling, then I don’t know what is. And I think that it’s kind of icky that people start putting a dollar amount on being ritually stringent.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Well, this is. It’s exactly how it went with the, in the secular world, with the food movement of getting everything organic and local and very pure. And then you also, like, unless you’re rich, would have no money left over, basically, if you did it.

Avi Finegold: Yeah. I mean, yeah, the. If you go to a Whole Foods and look at how many non-electric SUVs are in their parking lots and, and you know, are you. Which one are you with? Are you there because of X? Are you there because you know. So yeah, we virtue signal in ways in which it’s convenient for us and not in ways in which not which it’s not.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Avi, I could keep chatting with you about this all day. I don’t want to take up your whole day. But thank you so much for coming on The Jewish Angle. What have you got to what have you got? Apart from the obvious things which I will restate here, namely the Not in Heaven podcast and you’re writing for Scribe Quarterly. Anything else you want to specifically promote?

Avi Finegold: We have a project that is percolating. Stay tuned. It is going to be really, really exciting. I can’t say more about that. But yeah, The CJN has a really cool new project that is percolating that I’m really excited to be part of.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I am looking forward to it. Thank you so much, Avi.

Avi Finegold: Thank you.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Thank you for listening to The Jewish Angle, a podcast. Welcome to the podcast from The Canadian Jewish News. This has been Phoebe Maltz Bovy, opinion editor of The CJN and a contributing editor of Scribe Quarterly, The CJN’s print magazine. The show is produced and edited by Michael Fraiman. Our music is by Frank Fraiman. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, please subscribe to The Jewish Angle wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening.

Show Notes

Credits

- Host: Phoebe Maltz Bovy

- Producer and editor: Michael Fraiman

- Music: “Gypsy Waltz” by Frank Freeman, licensed from the Independent Music Licensing Collective

Support our show

- Subscribe to The CJN newsletter

- Donate to The CJN (+ get a charitable tax receipt)

- Subscribe to The Jewish Angle