Mordecai Richler wrote of Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg that his followers called him “the Skaryszewer Illuy, the Genius of Skaryszewer.

“My maternal grandfather was a Ba’al Shem, a Master of the Holy Name. He believed in devils… and, of course, Satan. Kesilim (poltergeists) also figured in his nomenclature.”

Richler acknowledged in his 1994 non-fiction This Year in Jerusalem that he was only four when Rosenberg died in 1935 and his fond memories are fragmentary and perhaps unreliable.

That has generally been true, despite Rosenberg’s prolific writing and strenuous efforts to ensure the vitality of Orthodox Judaism in the New World. He has been more legendary than historical until now.

Concordia University professor Ira Robinson’s new biography A Kabbalist in Montreal: The Life and Times of Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg (Touro University Press), for the first time, provides a well-researched scholarly treatment of this Hasidic maverick. The book will be celebrated at a virtual book launch at the Montreal Jewish Public Library on June 6.

Rosenberg was very much his own man, unafraid to go against the tide, even to the point of the quixotic. He devoted a quarter-century to his quest to make the Kabbalah accessible to the Jewish masses. Yet he was not a cloistered esotericist; Rosenberg was a gutsy combatant in the bitter, sometimes violent, struggle for control of Montreal’s kosher meat industry in the 1920s.

Rosenberg’s magnum opus was the translation of Jewish mysticism’s centerpiece, the Zohar, from the little-known Aramaic to basic Hebrew. In this seven-volume series, he also remastered the original to more closely follow the Torah sequence.

Robinson points out that this was not only a monumental task, but at odds with the attitude at the time among Orthodox rabbis that the Kabbalah was impenetrable to all but the most learned.

Rosenberg rejected that, believing the Kabbalah held wisdom that any Jew could grasp and was key to saving Orthodox Judaism in the 20th century. He was confident that once enough Jews were acquainted with it, the messianic era would be ushered in.

Rosenberg was both revered and dismissed, but always undeterred. He lived in poverty, even by the standards of the day, not helped by having 18 children (11 survived to adulthood). Richler’s mother Leah (Lily) was one of them.

Rosenberg’s birth was recorded on Dec. 31, 1860, in a village near Skaryzew in Russian Poland (a fact uncovered by Montreal Jewish genealogist Stanley Diamond).

Recognized as a prodigy, Rosenberg was a rabbi in Tarlow, Warsaw and Lodz, where he gained an early reputation with his commentaries on Jewish observance. He was also a storyteller, penning Hebrew morality tales about the heroic Maharal of Prague, and a healer, dispensing homeopathic remedies and magical spells.

In a seeming contradiction, he took a keen interest in the modern world. Thanks to his knowledge of Russian, he read up on science and new technologies, such as electricity, seeing no contradiction in their use and strict adherence to the Torah.

He was already 52 when he emigrated to Canada, motivated mainly by the hope of making a better living. For five years he was rabbi of Beth Jacob synagogue, a Polish congregation in Toronto where he unsuccessfully tried to unify kosher supervision.

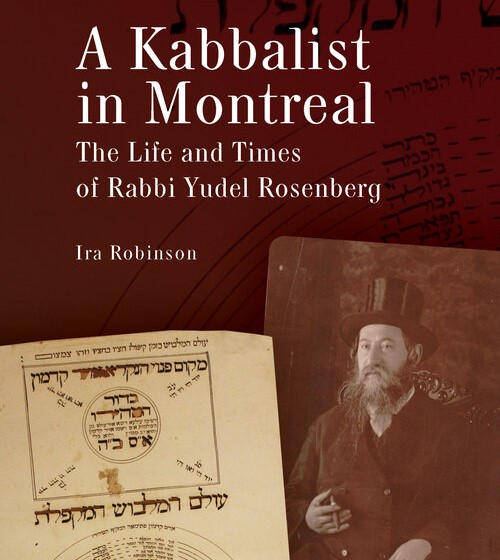

Thanks to the contribution of another grandson, Lionel Albert, a rare photograph of Rosenberg on the book cover reveals a confident figure in silk top hat, cigar in hand. Albert, now over 90 and living in the Eastern Townships, like his late cousin Richler, shares their ancestor’s scrappy character. Albert was an outspoken champion of English rights in Quebec.

As soon as he settled in Montreal in 1918, Rosenberg boldly went head-to-head with Rabbi Hirsch Cohen, the reigning kosher certification czar. Robinson provides a detailed account of a nasty battle that split the community with slaughterers and butchers lining up on one rabbinical side or the other.

The “kosher meat wars” raged for almost decade, with a brief truce when the Jewish Community Council (Va’ad Hair), which still exists, was founded in 1922. It was Quebec civil courts, and not a beit din, that eventually brought a shaky resolution.

Robinson, chair of Canadian Jewish studies at Concordia, has been fascinated by Rosenberg since he first heard about him 40 years ago. Rosenberg is not better known because he left few disciples and his family, though large and admiring of him, was too poor to immortalize him.

While the quality of Rosenberg’s voluminous oeuvre can be debated today, Robinson contends that he is exemplary for his creative and ceaseless attempts to reconcile fundamental Orthodox Judaism with modernity when its future was very much in doubt.

A Kabbalist in Montreal is launched virtually at the Jewish Public Library on June 6, the first of a three-part series that continues with an examination of the Rosenberg Rotulus, a vertical scroll created by Rabbi Rosenberg and donated to the JPL Archives in 2013 by his great-nephew, Dr. Lawrence Rosenberg, now president and chief executive officer of CIUSSS West-Central Montreal. On June 13, Yossi Chajes, the Sir Isaac Wolfson Professor of Jewish Thought at Haifa University, lectures on the scroll’s tree-shaped diagram which was used in kabbalistic meditation. On June 16, Crystal Maitland of the Canadian Conservation Institute discusses the treatment the fragile paper Rotulus underwent before it was returned to the JPL Archives in late 2020.