It’s a unique Israeli organization, belatedly formed by the Knesset to bring a sense of justice to the heirs of Holocaust victims.

The Company for Location and Restitution of Holocaust Victims Assets Ltd., headquartered in an office building in the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan, was established by an act of parliament in August 2006.

It started work just two months later.

A public, non-profit organization with a staff of 24, it’s empowered to track down the unclaimed assets of Holocaust victims in Israel – land, bank accounts, artwork and Judaica – and turn them over to their rightful heirs in Israel and the Diaspora.

Failing that, the company is required to transfer the assets to needy survivors in Israel – one-third of Israel’s 250,000 survivors live in poverty – and Holocaust education and memorialization forums.

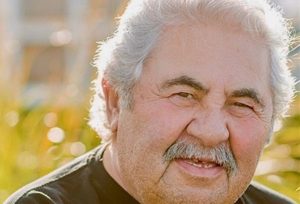

“We hope to find 20 per cent of the heirs,” company chairman Avraham Roet said in a recent interview.

Roet, a survivor from Amsterdam, Holland, was hidden by a succession of Dutch Christian families, and settled in Palestine in 1946.

His parents and three brothers were also saved by Christians, but his two sisters and a foster brother were murdered in Auschwitz.

Currently, the company holds assets with an estimated value of 750 million Israeli shekels, Roet said.

In addition, it has more than 100 plots of land.

Artwork and Judaica are held by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

The company was created by the Holocaust Victims Assets Law, whose passage was spearheaded by Labor party MK Colette Avital.

A former diplomat, Avital started the process by investigating dormant bank accounts in Israeli banks and land held by various institutions whose original owners were assumed to have been killed during the Holocaust.

Under the Holocaust Victims Assets Law, the company has been given 15 years to fulfil its mandate.

“We hope to finish fulfilling the greater part of our objectives in a meaningfully shorter period of time,” said Roet.

Last month, the Jerusalem Post reported, the company began returning 1.5 million shekels to a group of 15 heirs in Israel, South Africa and the United States.

The company’s budget for the first two years comes from the government. After 2008, the budget will come from management fees “charged over the company’s assets,” explained Roet.

Company shares are held by the Israeli government, but it has no direct control over the company.

Cognizant that a host of European countries have been grappling with the issue for decades now, Roet was critical of the Israeli government, Zionist organizations and banks in Israel for not having acted sooner.

“We believe the act of restitution could have and should have begun years ago,” he said.

Asked why Israel didn’t take the initiative in addressing the issue long ago, he replied, “That is a question you will have to ask the Israeli government.”

But banks, such as Bank Leumi, and the Israel Museum have been forthcoming and co-operative.

“Both are making efforts to resolve the situation,” he said.