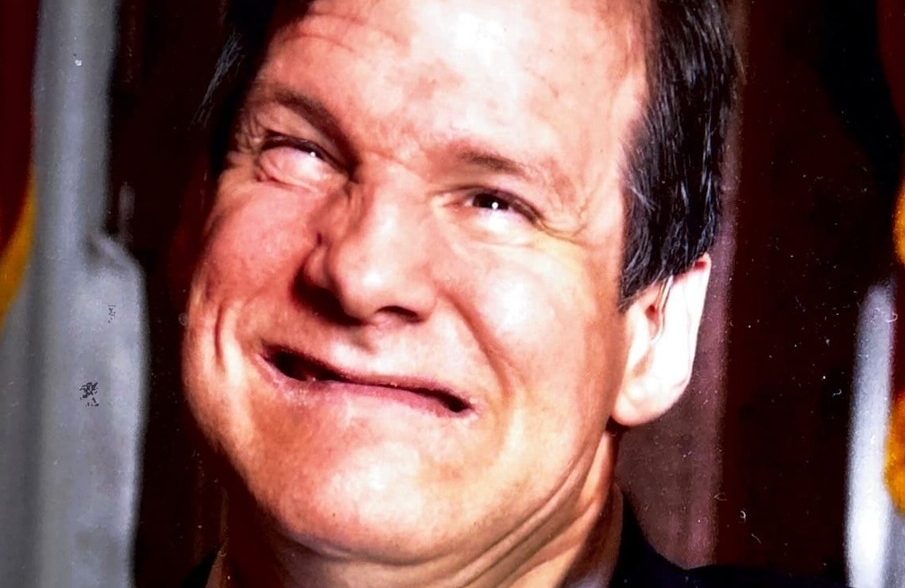

Muki Baum was the inspiration for the MukiBaum Treatment Centre, a centre for children with complex disabilities. He was a highly visible member of Toronto’s Jewish community, raising more than $750,000 for the centre, soliciting donations outside United Bakers Dairy Restaurant, Holt Renfrew in the downtown shopping corridor and other busy locations around the city.

He was also the 2009 recipient of the Queen Elizabeth II Ontario Medal for Good Citizenship, which recognizes people who, through exceptional long-term efforts, have made outstanding contributions to the well-being of their communities.

“Of course he did all the wonderful work to fundraise,” said Cheryl Perera, president and CEO of Aptus Treatment Centre (which is what the MukiBaum Treatment Centre is now called). “You can contribute to the world. You can enjoy your life. I think that’s the legacy he leaves behind. And I think that’s the same vision that his mom had: for people to live a good life.”

The funeral home’s website is filled with messages from people who encountered Muki in his wheelchair and recalled his warmth and joyful approach to fundraising.

He died in Toronto after a short illness on Dec. 6, 2024.

Baum was born in Israel in 1959 with a severe hearing impairment and cerebral palsy. His mother, Nehama, had a degree in social work, and specialized in working with families whose children had cerebral palsy.

At that time the medical diagnosis was blunt, recommending he be institutionalized. But Nehama persevered with the belief that all children deserve to live as independent a life as possible.

“Some people think that I am different because I have cerebral palsy, and I am deaf. But I want you to know that I am a person, not a disability,” Baum said in the 2013 film, A Day in the Life of Muki. “When I was born, the doctors in Israel told my parents that I was a ‘piece of meat’ that they would carry the rest of their lives.”

By the time Muki was 15, Nehama faced a challenge. In Israel, Muki was either the only deaf child among children who had cerebral palsy or the only child with cerebral palsy among children who were hearing-impaired. She sought a solution that would allow him to thrive.

She had contacts in four North American cities: Toronto, San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York.

“I came to Toronto and I found everything I needed right here. I saw a city that was safe. As an Israeli, I saw a city where people came to the road and pointed their finger, and traffic would stop to allow people to cross the street. I said, ‘That is where I want to live, because that is where Muki can live safely,’” Nehama said in a documentary entitled The Muki Baum Project, about her life’s work. She never went to the three other cities.

She admitted that adapting to Muki’s newfound independence was an adjustment.

“Muki wanted to go out. He wanted to walk. There were buses that he wanted to take. He wanted to take the subway. He wanted to be independent.”

In 1979, Nehama Baum founded the MukiBaum Treatment Centre with a vision of enabling adults, youth and children living with multiple disabilities to thrive in their communities.

Nehama worked with specialists in different fields to ensure that the centre offered innovative approaches to helping their clients. “Nehama Baum saw a Snoezelen Room and was determined to create one,” said Rose Schonblum, producer of The Muki Baum Project. Soon the MukiBaum Treatment Centre offered this multisensory therapy with lights and water that provides a relaxing experience to help reduce agitation and anxiety.

Brenda Lass attended an open studio clay class with Muki at the Jewish Community Centre’s Koffler Centre in Toronto, where participants were free to create whatever they wanted.

“It was so much fun. He had such a personality. I went into studio, and it was really me and Muki. And I got to know him there. He was making an Israeli flag on a board. The flag was probably 15 inches by 18 inches, and I used to ask him how it was going to fly!

“Then one week he decided he wanted to go on the potters’ wheel. You have to be a contortionist to fit on it—I could hardly do it. You get into the thing, and you lean over and you have to balance the clay. And to see the two of us trying to get him onto it…. We just laughed and laughed!

“And then I would see him at Lawrence Plaza some years later. Right away, he recognized me. He was creative. He would sell cards that he’d made. There’s no question that he loved doing it.”

“When you have a kid like Muki, there are a lot of things you can complain about,” his father, Moshe, said in The Muki Baum Project. “But when you look at the whole picture, if Muki wasn’t sent to us as he is, the MukiBaum Treatment Centre wouldn’t exist, and hundreds of thousands of people are being helped because of him.”

Nehama said, “There is a very beautiful story called, ‘I Wanted to Get to Rome, but I Went to Amsterdam.’ Someone went on the plane and they thought they were going to Rome, but they found themselves in Amsterdam. Now, Amsterdam is not as beautiful as Rome, but it has its own beauty. And this is the metaphor for having a child. You’re pregnant, you think and dream about how the child will be and what at life will be like with your baby and then your child. And then you have Amsterdam and not Rome.”

Muki Baum is survived by his father, Moshe. He is predeceased by his mother, Nehama, who died in 2022.